THE DOZENS: VIJAY IYER SURVEYS THE MUSIC OF ANDREW HILL by Ted Panken (editor)

In 1995, Vijay Iyer, then a 24-year-old Berkeley PhD candidate in Physics with an interest in the neurobiology of musical cognition, who was moonlighting as a gigging jazz pianist in the Bay Area, met educator/trombonist/computer installation artist George Lewis. George set forth the idea of framing improvisation itself as a kind of inquiry, or critique or intellectual discourse, without losing the soul or heart of the music, Iyer once recalled.

Now 37, and a New Yorker since 1999, Iyer is one of the most prominent experimentally-oriented jazz musicians of his generation, a position bolstered by a discography that includes 12 Iyer-led CDs, most recently Tragicomic (Sunnyside), that constitute his artistic response to the question Who am I?

In titling his twelfth album Tragicomic, Iyer was thinking about the blues. To be specific, he cites the use of the adjective by Cornell West, the African-American philosopher-culture critic, to describe the sensibility at play in an existential attitude that West calls the blues aesthetic. Not to be mistaken for the musical blues form, the blues aesthetic reflects the world view that emerged among African-Americans after slavery was abolished in the United States, which bedrocked much of 20th century jazz and popular music expression, not to mention the blues as such.

West described the blues aesthetic as stemming from a sustained encounter with the absurd condition of being a new kind of person, who had been owned as property and now had a certain amount of freedom, but also still faced injustice everywhere, Iyer said earlier this year. It was the way they found to continue being who they were. Its not exactly humor. Its tragicomic joy and sadness come together

A self-taught pianist whose jazz obsession began in high school, Iyer honed an early affinity for the percussive orientation of hardcore New York School pianoEllington, Monk, Bud Powell, Elmo Hope, Randy Weston, and Cecil Tayloras an undergraduate at Yale, where he majored in math and physics and led a trio and sextet. He discovered the experimental tradition of Creative Music-Jazz in an undergraduate course with Sun Ra biographer John Szwed, and evolved into an unrepentant free jazz zealot.

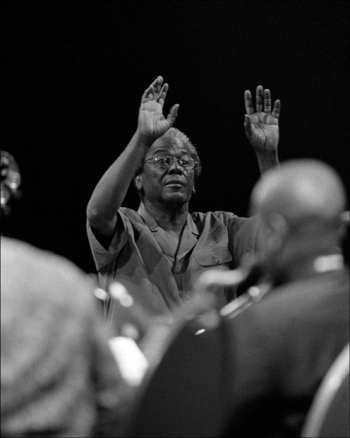

During these years, Iyer also discovered the music of the pianist-composer Andrew Hill [1931-2007], who developed his sui generis concepts in the blues culture of 1940s South Side Chicago, his home from the age of three, where the unorthodox was the norm. Early on, Hill drew influence from boogie-woogie king Albert Ammonsas he put it in 2001, his boogie-woogie was a living thing; he created with it, In that 2001 Down Beat article, Hill went on to discuss how his environment affected his sensibility:

As a teenager delivering the Chicago Defender, Hill met Earl Hines, and bugged him to death until he decided he would let me play something on his grand. I played something in D-flat, and he was amazed not only that I could hear, but I had a technical facility for not having really studied. What I liked about Earl Hines was that he played AB-AABA form, but at a certain point he would deviate and play something creative outside the structure; when I talked to him he said, Well, thats what we call concertizing. Hill also admired the lesser-known pianist Willie Jones (he used to play with ninths in the bass and had a nice single fingering, even though he was known around Chicago for his exciting block chord Milt Buckner approach; I would call him an early Cecil Taylor, someone who would place their style on a 20th Century composer) and Sun Ra.

Sonny had a basic Chicago approach, Hill remarks. Even on a Blues you would go Out and you would go In. A lot of people cried when they first heard Ornette and a few others, but to an extent that style really developed in Chicago. Chicago was a very interesting place when I was growing up. There wasnt anyone lettered or intellectual about the music, or about what someone else was doing; it was a venue big enough for everyone to flourish and do their thing. But it was category-less. It was organic, like an African modal situation, in which the performer would play in all the different voices. Jazz wasnt an art form; before television and integration got strong, it was the spiritual element that kept the community together. The music was coming from the streets. Most people talk about Blue Note like it was a philanthropic institution! It wasnt that. It carried the heartbeat of the popular music in the black communities. Thats why people could really play by ear in those days, because it was so accessible.

As his teens progressed, Hill also absorbed recordings by Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk as they came out, plugging his turntable into a guitar amplifier so I could almost hear them the same way that I heard the live artists. He found someone to show him Czerny technique to get the fingering necessary to grapple with Powell. He and a gifted friend named King Solomon, used to pride ourselves on the fact that we could lift Monks stuff off the records when I was 16 years old—it came natural to him because he was a church pianist; after he taught me the church perspective, Monks concept became more accessible."

Just as Hill found a narrative context for his highbrow ideas within the church perspective and the blues, Iyer, who is the son of immigrants from South India, found his in melding advanced jazz harmony with surging vamps and ostinatos drawn from the intricate cycles of South India and West Africa, illuminating precise symbolic connections between personal imperatives and the stories, images and states of mind encoded in the rhythms he deploys, which, after all, originated in the service of social ritual.

I was thinking about what it means to be American today, Iyer told me of Tragicomic. I have a particular transnational scope; my perspective is very much American, but inflected and informed by Indian histories and heritage. We can all learn from and participate in the blues experience. The blues is not just a kind of music. It has to do with a certain cry, a desire to be heard, a refusal to be silenced.

In producing his Andrew Hill Dozens, Iyer decided to generate his thoughts on a baker's dozen of tracks from Hills oeuvre through conversation. Hence, the remarks below stem from of a dialogue between Iyer and the editor.

There are some great Hill recordings from the past decade, but because theyd received so much attention in recent years, I decided to focus mostly on his earlier work, which I find indispensable.

Andrew Hill: Chiconga

Musicians:

Andrew Hill (piano, vocal(?)), Malachi Favors Maghostut (bass),

James Slaughter (drums), unidentified percussionist

.Composed by Andrew Hill

.Recorded: Chicago, Late 1956

Rating: 95/100 (learn more)

This is from a very early recording of Andrews with his working trio in the 50s that mainly did standards. In that context of a more workmanlike set of standards, this stands out as a piece of art music. It prefigures things to come for Mr. Hill. Theres some singing, which sounds like it might be actually Hill himself doubling the melody with his voice. Its a very haunting dirge-like bluessort of related to Black and Tan Fantasy, and maybe also Creole Love Call, because of this mysterious vocal part. More importantly, it documents an encounter with an unidentified percussionist who is playing various hand drums, bells, and things like that. In a way, it reminds me of some of these pan-Africanist projects from the previous decade, like the stuff with Chano Pozo and Dizzy Gillespie. It has an episodic mini-suite form, even though its only a few minutes long.

At one point, the percussionists tempo is imperfectly matched to what Andrew and company are doing, so the two have a mysterious relationship to one another. That aspect prefigures the prominent percussion-piano relationships on Compulsion. Once I heard Andrew refer to the blues as a rhythm above all else, and you hear that sensibility in his brief solo on this tune. The rhythmic fluidity and expressiveness of his phrasing sounds straight out of blues. He comes off on the rest of the disk as an accomplished straight-ahead player, in a way that might surprise some people. Theres a version of Old Devil Moon thats really in the pocket, swinging, rhythmically strong, intricate, and precisely arranged. I think its interesting to hear the amount of skill and dexterity he had with rhythm in a more traditional context. Later on, he was often heard as someone who was just rhythmically out. But when you hear his deep foundation in these groove-based approaches to rhythm, you realize that the later stuff actually wasnt so outit was more as if he reached further in. Its interesting historically and theres a lot to learn from it, so Id give it a 95. Its a fascinating moment from Andrews pre-Blue Note era.

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

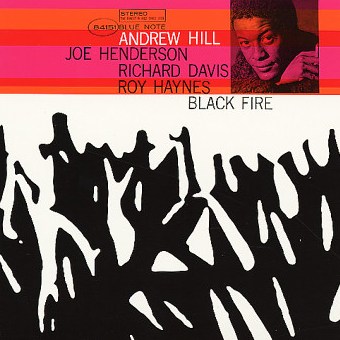

Andrew Hill: Subterfuge

Recorded: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, November 8, 1963

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

This is from the great album, Black Fire, which also features one of my favorite saxophonists, Joe Henderson. Everyone is great form. I probably zeroed in on this trio piece because Im thinking a lot about piano trio music right now, but also because its so powerful. This album has mystified and excited me since I got it about fifteen years ago. The group is unified to an astounding degree, all the elements resonate with each other, which gives the group such a powerful sound. Roy Haynes sounds incredible, all the very animated work on the snare, and hes present in the mix in a way that drummers usually werent on Blue Notes Van Gelder sessions. When a drummer is that present in the mix, which is usually how I prefer it to be on my own albums (and sometimes I get flack for this), you really hear the counterpoint with the other instruments. Its much more centered: you hear the drummer not just as a supportive instrument, but as a central member of the group. It sets off all the rhythmic intricacies that Andrew is doing, how he fits in all this stuff between the beats. I love the way Hill lands synchronously with Haynes so forcefully and so frequently. His rhythmic solidity is so palpable, and his playing is very extroverted and active. Its not like hes just floating. Hes always anchored in the time. Its inspiring to hear such advanced rhythmic expression.

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

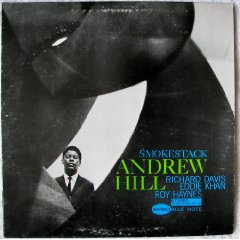

Andrew Hill: Smokestack

Recorded: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, December 13, 1963

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

This is one of my favorite albums of all time, of any artist, on any instrument. It takes Richard Davis and Roy Haynes, who rounded out the trio on Black Fire from a month before, and augments it with a second bass player, who becomes a kind of X factor. It frees Richard Davis to orbit the group, rather than anchoring it, and Eddie Khan, it seems, ends up taking more of the traditional bass player role. Theres something so powerful about the driving rhythmic vortex, the rhythms spiraling around each other, between Haynes and Richard Davis and Eddie Khan. Eddie Khan is playing this vamp, a clave pattern, driving the rhythm. If you were to notate it, it would be two dotted quarters and a quarter over the course of four beats, which is that classic Afro-Caribbean rhythm thats ubiquitous in American music. But then, what Richard Davis does across that is a warped version of that pattern, which tumbles across the barlines. So what Eddie Khan is doing fits squarely in the bar, while Richard Davis reaches past it. You get this very sharp rhythmic relationship, like a high harmonic relationship, if that makes sense.

Theres an alternate take, and in the take that wasnt used, Eddie Khan is walking, while Richard Davis plays very much the same. When Eddie Khan is walking, the relationship between the two basses isnt quite as interesting. Its simpler, and that seems to hold it back, compared to the intensity of the rhythmic space that they created in the take that was chosen. Then also, Roy Haynes is so playful. Its not like hes just playing a square beat or anything like that. Hes playing interactively and as inventively as ever. This is some of my favorite examples of Roy Haynes on record, actually. Its so alive. Then, too, the song itself has such majesty to it, such mystery. Its a harmonic maze of its own. So the whole thing, with all these different rhythmic layers and the harmony being a progression that doubles over on itself. . . Its like the whole thing is this massive polyphonic labyrinth. Its incredible.

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

Andrew Hill: Refuge

Musicians:

Andrew Hill (piano), Eric Dolphy (alto sax), Joe Henderson (tenor sax), Kenny Dorham (trumpet), Richard Davis (bass), Tony Williams (drums).

Composed by Andrew Hill

.Recorded: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, March 21, 1964

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

Point of Departure is one of the first CDs I ever bought, around 1990 or 1991, when I first got a CD player, when I was 19 or 20 years old. I had to save up! Prior to that I was all about vinyl and cassettes. That makes me feel old. Anyway, this is a landmark composition of a landmark recording, with such an intense combination of virtuosos. Everybody sounds great on it, and its simply a classic! I remember in the liner notes Hill called it a blues, which is mysterious, because it has all these chords that you dont associate with the blues, and it feels like a long form; its actually a 24-bar progression in 6/4, so it has this sort of large extent to it. But if you hear each 8-bar section as if it were one-third of a blues progression, then that alignment makes more sense. But I also feel that the alignment with blues is more conceptual.

I transcribed the piece at one point for a performance in Oakland that was a tribute to Eric Dolphy, and we tried to do a bunch of things that Dolphy was featured on in addition to his own music. I had to sit with this one for a long time, because some mysterious stuff goes on with the inner voices. I dont remember exactly, but I think this was the piece that Andrew referred to in the liner notes either to the Mosaic box set or the original album. He said something about finding the mode that works over the entire song. Its as though some set of common tones persists through the entire harmonic progression, which, when you look at the changes, is counter-intuitive, because there are a lot of passing chords that seem to move through different keys. But then, when he improvises, you hear the unity.

Anyway, this is a masterful composition. The solos are great. Dolphys entrance is one of the great musical moments of the whole album. Tony Williams sounds incredible. Its fascinating to hear Tony Williams with Richard Davis and Andrew, this intersection of these different streams of creativity from the 60s.

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

Andrew Hill: Siete Ocho

Musicians:

Andrew Hill (piano), Bobby Hutcherson (vibes), Richard Davis (bass), Elvin Jones (drums).

Composed by Andrew Hill

.Recorded: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, January 8, 1964

Rating: 99/100 (learn more)

This is a fascinating intersection, because we have Andrew Hill with Elvin Jones, two powerful forces. Also, Hill and Bobby Hutcherson had a powerful relationship over the decades, which is well crystallized on this album. This is their first recording together; Dialogue came later. Its a great composition. As the title suggests, its a 7-beat metrical form. The head is 20 bars. Andrew loved these irregular forms. Often the three-fold nature of the blues form came through in his compositions, even if they didnt strictly adhere to that exact form. Its more like these different sections would answer each other in unexpected, irregular ways that got away from the Tin Pan Alley, 32-bar format. He had interesting ways of grouping things.

Everything about this piece is greatthe intensity, the lyrical quality, and especially hearing Elvin Jones drive this 7-beat cycle. Elvin sounds fantastic. The bassline is this insistent vamp, a rhythmic ostinato that persists throughout, and Richard Davis, perhaps more than is typical for him, anchors that rhythmic figure very firmly. I think often that happens when you introduce novel rhythmic structure: people hew to the written foundation a little more, because its less obvious how to depart from it. But here, because Davis does that, it frees up everyone else. Things get a bit ragged at times, but thats because theyre reaching beyond the obvious. For example, what Andrew does in his solo strikes me every time I listen to this track. He creates his own rhythmic gravity. Towards the climax of his solo, the original rhythm becomes dwarfed by the intensity of his own rhythmic space that hes creating, so you hear that 7/8 part as a mere satellite orbiting Andrews solo. Its mesmerizing.

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

Andrew Hill: Euterpe

Musicians:

Andrew Hill (piano), Freddie Hubbard (trumpet), Joe Henderson (tenor sax), Richard Davis (bass), Joe Chambers (drums).

Recorded: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, February 10, 1965

Rating: 99/100 (learn more)

This one burns. Freddie Hubbard and Joe Henderson were dealing at a really high level in this post-bop context. Super chops and amazing creativity, dealing with the structure of the tune in such detail and with great power, clarity, polish and dexterity. Its great to hear Andrews music realized on that level. Someone in music school today could learn a lot from this, because it has all the things that they strive for, and also all these other things that they dont tend to work on. The tunes structure is interesting, because the bridge sort of cracks open. Its extended and suspended, and it recurs every chorus in a way that seems to destabilize the song. Its an interesting balance, because usually the bridge is a temporary reprieve from the main section of the tune, but here it almost takes over. I love Joe Henderson! I could do a whole other playlist on him alone. Freddie is blazing on here, too.

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

Andrew Hill: Compulsion

Musicians:

Andrew Hill (piano), Freddie Hubbard (trumpet), John Gilmore (tenor sax), Cecil McBee (pizzicato bass), Richard Davis (arco bass), Joe Chambers (drums),

Nadi Qamar (African drums, African thumb piano, percussion); Renaud Simmons (percussion)

.Composed by Andrew Hill

.Recorded: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, October 8, 1965

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

Compulsion is one of my all-time favorites. I can say right now that the whole album, and particularly this piece, gets 100! People see this album as Andrews kind of breakthrough into the avant-garde. Whats amazing about it for me is that its so carefully orchestrated and compositional. He has sculpted this series of spaces for improvisation to take place. They end up being solo features, but the texture for each solo is specific and beguilingthe way he worked with the percussionists to create these sort of vortices, these swirling textures, as well as the incredible sonics he elicits from the piano. For the most part, its not really tonal. These orchestrated motives connect the different sections, and in his accompaniment to the solos by John Gilmore and Freddie Hubbard Andrew elicits these terrifying resonances from the piano that make you rethink aspects of harmony. Everything he plays feels so right even though it doesnt seem to have any obvious connection to tonality that were used to. Its more than a breakthrough into the avant-garde; its a real breakthrough with harmony and texture and form. Then, to hear John Gilmore in this context is so incredible, too. Its rare to hear him outside of Sun Ras context, and, of course, they had this Chicago connection. John Gilmores solo entrance. . . if you just hear a few seconds of it, you could mistake it for a Sun Ra record, not even necessarily from this period, but from later on, like the 70s. So theres something visionary

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

Andrew Hill: Desire

Recorded: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, March 7, 1966

Rating: 98/100 (learn more)

I love the vibe of this piece. Its very focused and dark, with a kind of lope to it. The bassline is really simple, but the way its played is evil! I mean that in the best way. Its beyond bad! A mess!! I think what really sells it for me is that Walter Booker is playing almost a quarter tone flat, but because its in the bass register, it somehow works. It creates this sustained harmonic instability. Hes only playing two notes, the V to the I. I think its C-minor. But because its flat in just the right way, it warps and expands the richness of the spectrum harmonically; it thickens the tonal space. Its a trance-like bassline that keeps repeating, and Andrew seems to be almost sleepwalking. I use the word gone about the way hes playing there. I can immerse myself in it. Its great to hear Andrew and Sam Rivers together.

Theres an alternate take of this tune, on which the bassist is more active. Hes interacting and sometimes walking. But I like the trance version better. I think the bending of the pitch enhances that, because it blurred the whole picture in such an interesting way. The reason it doesnt get higher than 98 is because its sort of static, but I like the stasis.

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

Andrew Hill: Illusion

Musicians:

Andrew Hill (piano), Bennie Maupin (tenor sax), Ron Carter (bass), Mickey Roker (drums),

Sanford Allen (violin); Selwart Clarke, Al Brown (viola); Kermit Moore (cello)

.Recorded: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, August 1, 1969

Rating: 98/100 (learn more)

This is Andrew with a funky rhythm section and string quartet, and Bennie Maupin enters pretty far into the song. At first I thought that he wasnt even on this track, but he is. What grabbed me about this is, on the one hand, the way Mickey Roker plays, which is this kind of low-down groove, steady and centered, with a lot of character to it, like James Brown at two-thirds speeda mellow James Brown groove. Then theres Ron Carter, who is very good at handling this sort of thinghe can play the same thing over and over again and give it life, and find subtle and interesting ways to vary ostinato basslines. That rhythm section is in interesting contrast to the very graceful and lilting string writing that feels almost incongruously elegant across that groove. It sets up a nice space, and Andrew straddles those two textures or tendencies. A nice, unexpected delicacy.

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

Andrew Hill: California Tinge

Rating: 99/100 (learn more)

This is a great example of Andrew Hills abundant solo piano music from the 70s and 80s. It has a unique qualitythis kaleidoscopic polyphonythat you come to recognize from him. I guess it wasnt documented prior to the 70s; it may be that hed already achieved these sorts of techniques much earlier. A lot of this stuff emerged later on. For example, this wasnt issued until last year. Theres a previous record, From California With Love, which is from the same sessions. It may have been that no one was paying for him to make ensemble records any more after the eighteen sessions he did for Blue Note, with only a third of those released. Anyway its nice to see his solo concept start to emerge with such flair, virtuosity, and majesty. At any moment you feel like youre hearing something thats authentically part of the jazz piano tradition, but its unique in the persistent irregularity of how the moments string together. It takes such an unexpected path: ambling, lurching, sly, dazzling. Its like a history of jazz piano atomized, a deconstruction of the piano tradition. Yet theres a real throughline, too. You really hear the song being played; its just that hes strolling through the musics unconscious, letting it all speak through him.

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

Andrew Hill: Verona Rag

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

Basically, whats always drawn me to Andrew Hills music is that its so mysterious. It challenges your sense of what music is. You cant really listen to it as style, like, Oh, this is a great example of hardbop, or postbop. To me, it just explodes all those categories. Its something much more fundamental about existence. I listen to it on those terms, like its telling me something about consciousness or about life. When I give a piece a grade of 100. . . I dont know how it would stand as a piece of music, because to me its something larger than that.

Heres something I wrote earlier about Verona Rag for Destination-out.com:

How can one piano piece contain the universe? Somehow this one does . . . It is and is not a rag in the traditional sense; it has a traditional rag form, maddening repeats included, but it also spirals off at times---into fragments of other songs, into glacially paced anti-rag ruminations, into what seem like the recesses of human consciousness. It has glaring imperfections and yet also seems perfectly balanced. Its pulse careens, wobbles, and falters, but this results in a more accurate portrayal of human motion than any piano roll ever could capture. It pushes a quintessentially ragtime hemiola figure to an absurd extreme. It is simply a tour de force explosion of the idea of rag.

Hill constantly allows the two hands to slide slightly out of register, enhancing the polyphony while peeling the rhythm apart like an onion, revealing musical pulse to be a mere convenience, a collective fiction. There are times when Hill seems to be fooling with us, but then you turn a corner and glimpse certain mysteries of existence. Check out the passage starting at 8:45 where he refracts the C section, spinning these intoxicating lines across an insistently asymmetric sub-basement left hand, only to hit the last chord with deadpan simplicity each time.

The song ends suddenly, with a dash of elegance and humor, and it feels like the right time to make an exit. The listener has been put through the wringer. You are bewildered and have forgotten what life was like before the song started. But, as Wadada Leo Smith said in this clip from the film Eclipse:

The artist is the consciousness of society, but musicians role is very special. Its a way of making an example of the perfect state of being for the observer, causing, if its successful, the observer to forget just for a moment that there is anywhere else existing except that moment that theyre engaged in, and to eclipse everything that was happening to them before they began that process of being the observer, or being involved and engaged between art and music and listening, and to transform that life in just an instant, so that when they go back to the routine part of living, they carry with them a little bit of something else. (Smith, Eclipse)

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

Andrew Hill: Golden Sunset (alternate take)

Musicians:

Andrew Hill (piano), Bobby Hutcherson (vibes), Greg Osby (alto sax), Rufus Reid (bass), Ben Riley (drums).

Recorded: Englewood Cliffs, N.J., January 30-31, 1989

Rating: 98/100 (learn more)

This is from one of a couple of records that Andrew did for Blue Note in the late 80s. The album itself has a certain coldness, which I think has to do with the way it was recordeddirect to digital two-track, with digital reverb on the drums, and everything sounds a bit cold. Particularly the sound of the bass is nasal. Its a strange mix, which for me diminished what could have been this records impact as a comeback or whatever you could call it. But this song nonetheless is quite powerful, and everyone plays beautifully on it. To me, the alternate take, which is about half as long as the one that was chosen to be released, is the more focused, more intense of the two. The other one was more sprawling and a lot more things happened in it, but the power of the song is watered down. Greg Osby sounds great. Its a beautiful song, delivered with power and grace. A nice gem from Hills later years.

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer

Andrew Hill: Seven

Recorded: 1998

Rating: 99/100 (learn more)

This is a solo piece composed by Russell Baba. I saw Andrew play with Russell at the San Francisco Asian American Jazz Festival, maybe a couple of years before this was recorded. He had a longstanding relationship with Russell from the 70s. This is a straight solo record that Andrew did in the late 90s, after not having released much that whole decade. Its a live record at a small club in France. On this song, he gets a powerful resonance out of the instrument, great clouds of sound. Ive always cherished Andrews sound. He gets the instrument ringing in a way that reminds me of Monk, Duke Ellington, McCoy Tyner, and...well, not many other people. You can tell that he cherishes that physical sensation that the piano gives you when you get it really ringing and shaking. You just feel it. It starts to play you. Andrew was able to cut through a rhythm section and still get that depth of sound with that kind of technique, and it often means he plays a little less than, for example, Tommy Flanagan, who was also a percussive player but fleet and delicate as well. Just a different perspective. Here its really about physics and getting the whole room resonating. Theres something very majestic and almost sacred about it.

Reviewer: Vijay Iyer