THE DOZENS: ETHAN IVERSON ON STRIDE PIANO by Ted Panken (editor)

Editor's Note: Music fans, jazz-oriented or otherwise, may know Ethan Iverson solely as the pianist in The Bad Plus—the increasingly popular collective trio in which he, bassist Reid Anderson, and drummer Dave King "put the streets" into repertoire primarily comprising original compositions and less traveled "new standards" of the late Baby Boom and Generation X. Or, for that matter, they may remember him as one-time Musical Director of the Mark Morris Dance Company. In either event, they might be surprised at the 35-year-old pianist's deep knowledge of and passion for the jazz lineage.

This will not be the case with readers of "Do the Math," the Bad Plus blog-webzine for which, over the past year, Iverson has offered some of the finest jazz criticism presently available in print or hypertext—a socio-musicological analysis of the music of Lennie Tristano, informed interviews with Billy Hart, Ron Carter and Stanley Crouch, and, most recently, a five-section piece on the "Young Lions" generation of the '80s, headlined by an exhaustive conversation-blindfold test with Wynton Marsalis.

In light of these formidable bona fides, it seemed logical to ask Iverson to contribute a guest artist Dozens. That he elected to go with a dozen creme de la creme stride piano selections is no surprise in light of the following remarks, cited a few years back in Keyboard magazine.

"The first three generations of jazz pianists were monster soloists who played with both hands all over the instruments," Iverson stated, referencing Art Tatum, Jelly Roll Morton, and Albert Ammons. "They've got a whole scene going that in some ways is closer to Chopin than any 'modern jazz' is. I want to play the whole piano dynamically and with both hands." T.P.

by Ethan Iverson

I'm taking the definition of "stride piano" to mean a swing beat, "oom-pah" in the left hand, and the potential for improvisation. Professionals of stride (of which I am not) are surely more specific. All of these artists recorded multiple masterpieces; in many case my final choice was nearly random. The selections are presented in chronological order of recording.

There are plenty more stride performances to consider. Another dozen more tracks could easily be selected from artists like Eubie Blake, Fletcher Henderson, Luckey Roberts, Jess Stacy, Count Basie, Herman Chittison, Teddy Wilson, Johnny Guarnieri, Mary Lou Williams, Hank Jones, Sun Ra, Dick Wellstood, Dick Hyman, Jaki Byard, and Marcus Roberts.

James P. Johnson: Keep Off the Grass

Track

Keep Off the Grass

Artist

James P. Johnson (piano)

CD

Harlem Stride Piano 1921-1929 (Jazz Archives 111)

Recorded: New York, October 18, 1921

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

They called him the father of stride piano, the king of the Harlem rent party.

In terms of keyboard geography, the space between the "oom" and the "pah" is always very far in James P's left hand. This piece is also quite fast; few other jazz pieces from this era are as brisk. Everything considered, "Keep Off the Grass" is fearsomely difficult to play.

Part of the real Harlem stride style is how single notes do not dominate the melody; instead, constant constellations of double notes (and sometimes chords) brassily sing on top. The first strain of "Keep Off the Grass" has a mysterious chromatic "thumb line" (the lower note of the dyads and chords) that, if isolated, would be quite Monkish in nature.

The last (and most improvised) strain is composed of falling diminished chords. After nearly a century of increasingly advanced jazz harmony, it is hard to hear them as provocative today. In 1921, though, I'm pretty sure James P. would have meant those chain sequences of diminished chords to mean uncertainty and perhaps even sadness: the tear beneath the smile.

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson

Jelly Roll Morton: Grandpa's Spells

Track

Grandpa's Spells

Artist

Jelly Roll Morton (piano)

CD

Jelly Roll Morton: 1923-1924 (Milestone 47018)

Recorded: Cincinnati, Ohio, June or July, 1924

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

This was recorded after "Keep Off the Grass," but it was reportedly composed a decade earlier. (At any rate, Morton is usually considered the influence on James P., not the other way around.)

"Grandpa's Spells" is nearly a rag in feeling, except with a swing beat and a generally rougher feel. A lot of the time Morton plays overtones in the left hand (usually the fifth note up from the bottom) that imply drums while the brilliant graces on top imply New Orleans-style clarinetists. The F-major trio features a left-hand smash, a dark cluster tossed off casually like a whiskey bottle kicked under the piano.

The sheer strength of Morton's playing is remarkable. Sometimes I read that such-or-such stride or early jazz pianist has a 'delicate' or 'subtle' touch. There are complicated and refined elements in all the pianists on this list, but all of them also knew how to make the piano project: you could hear them even through a wild revel.

Morton is commonly considered the first great composer of jazz. He was also surely one of the greatest dance pianists in history.

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson

Earl Hines: A Monday Date

Track

A Monday Date

Artist

Earl Hines (piano)

CD

Earl Hines and His Orchestra: 1928-1932 (Queens, NY, December 8, 1928)

Recorded: Queens, NY, December 8, 1928

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

The solo rendition of this Hines standard is even better than the famous Hot Fives version with Louis Armstrong. (Important note: I am discussing the 12/8/28 version timed at 2:53, not the one recorded the next day.)

Hines must have had enormous hands to play those big marching and striding tenths so quickly and authoritatively with his southpaw. His right hand grabs big clusters and chords, too: this is a hell of a lot of piano.

There's always something engagingly ragtag about a Hines performance. In fact, those signature weird stops and pauses - surely only Hines was doing this in 1928! - are really off the grid, sounding dangerously like moments of free improvisation. Hines always keeps the beat, of course, but not even Art Tatum is as fearless about pursuing the unknown - or rather letting the chips fall where they may. (Hines's piano break on "Savoyager's Stomp" with Armstrong - also 1928 - is the height of avant-garde.)

Of all the pre-bop pianists, Hines had the longest career as a solo pianist - his final recordings from the '70s are as interesting and provocative as his first 1928 sides.

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson

Fats Waller: Numb Fumblin'

Recorded: New York, March 1, 1929

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

Waller was the most overtly humorous of any serious jazz musician. Nothing could be more ironic than his title for this spacious, slowly paced but bouncing blues.

Waller had the best trills of any jazz pianist. He shows them off here not only as single notes but in double thirds as well. Waller said offhandedly that he studied with classical über-virtuoso Leopold Godowsky; as far as I know, this is unproved, but the last chorus of high-register passage-work in "Numb Fumblin'" has a kind of effortlessly manic Art Nouveau elegance not far from Godowsky's world.

The emotion of "Numb Fumblin'" is perverse, joyous, and groovy. Classic Fats!

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson

Willie 'The Lion' Smith: Echoes of Spring

Track

Echoes of Spring

Artist

Willie 'The Lion' Smith (piano)

CD

Willie 'The Lion' Smith: 1938-1940 (Classics 677)

Musicians:

Willie 'The Lion' Smith (piano).

Composed by Tausha Hammed, Willie 'The Lion' Smith & Clarence Williams

.Recorded: New York, January 10, 1939

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

The 'Lion' liked to act and talk real tough, but paradoxically he was the Harlem stride master most interested in gauzy, impressionistic harmony and classically structured piano pieces. Duke Ellington always credited Smith as an important influence.

"Echoes Of Spring" features an unforgettable melody floating over arpeggios before the heat gets turned up a little bit. Although Smith never really plays the requisite left-hand 'oom-pah' in this piece, the stride feeling is there somehow.

I'm not sure if we always get the real deal with Smith's records. While his compositions are supremely beautiful, there is something occasionally self-conscious, rushed and even sloppy about his performances. Not everybody records as easily as the next person, and I wonder if the Lion was really comfortable in the studio.

Highly recommended is my pal Spike Wilner's book of Willie 'The Lion' Smith transcriptions with accompanying essay (The Lion of the Piano: 8 Piano Compositions by Willie 'The Lion' Smith). These wonderful compositions are surely ripe for an interesting contemporary repertory project.

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson

Joe Sullivan: Gin Mill Blues

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

Joe Sullivan was a powerful pianist associated with the other great white Chicago jazz players of his era. Like Waller's "Numb Fumblin'," "Gin Mill Blues" just saunters along without trying too hard. (There are plenty of trills here, too, including one in double thirds!) Especially charming is the ending, with a chromatic flourish wistfully resolving to a soft simple triad in the high register.

In Ross MacDonald's The Moving Target (1950), private eye Lew Archer gets hung up on this track while failing to successfully interrogate his suspect Betty Fraley:

But hot piano wasn't my dish, and I'd picked the wrong words or overdone my praise. The bitterness of her mouth spread to her eyes and voice. "I don't believe you. Name one."

"It's been a long time."

"Did you like my 'Gin Mill Blues?'"

"I did," I said in relief. "You do it better than Sullivan."

"You're a liar, Lew. I never recorded that number. Why would you want to make me talk too much?"

"I like your music."

"Yeah. You're probably tone-deaf." She looked intently into my face. "You could be a cop, you know. You're not the type, but there's something about the way you look at things, wanting them but not liking them. You've got cop's eyes - they want to see people hurt."

"Gin Mill Blues" is right: Sullivan, like too many of the other pianists on this list, sadly died of alcoholism. It was an occupational hazard, since standing the working pianist rounds at a convivial gathering is only the right thing to do.

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson

Art Tatum: Runnin' Wild

Recorded: New York, August, 1938

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

Any Tatum performance could be selected as the final word on common-practice stride. I chose this one because it is the title piece from the James P. Johnson revue that exploded "The Charleston" the world over. Tatum had tremendous respect for Johnson (and Fats Waller too). It is easy to hear this version of "Runnin' Wild" as a tribute.

One detail under-discussed in the Tatum literature is his swinging beat. It is almost too much: Not only is Tatum the greatest pianist technically, among the most advanced harmonically, and unrivaled when casually recasting a pop tune's melody as an improvised effusion - Tatum swings incredibly hard.

Occasionally I see reference to Tatum as a glorified cocktail pianist or a musician unconversant with the blues. These charges are ludicrous. Tatum was just the best, that's all: it may be hard to accept, but it's true.

I am not religious, nor even particularly spiritual. But when I consider the depth of accomplishment Tatum had from a youthful age, as a nearly blind, black man from Toledo, Ohio in Jim Crow times, I can't help but acknowledge that he must have had unearthly assistance. Fats Waller said it, when Tatum dropped by his gig: "I play the piano, but God is in the house."

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson

Duke Ellington: Across the Track Blues

Track

Across the Track Blues

Artist

Duke Ellington (piano)

CD

The Duke at Fargo, 1940: Special 60th Anniversary Edition (Storyville)

Musicians:

Duke Ellington (piano), Rex Stewart (cornet), Ray Nance (trumpet), Wallace Jones (trumpet), Joe "Tricky Sam" Nanton (trombone), Juan Tizol (trombone), Lawrence Brown (trombone), Barney Bigard (clarinet), Johnny Hodges (alto sax), Otto Hardwick (alto sax), Ben Webster (tenor sax), Harry Carney (baritone sax), Fred Guy (guitar), Jimmy Blanton (bass), Sonny Greer (drums).

Composed by Duke Ellington

.Recorded: Fargo, North Dakota, November 7, 1940

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

As the premier bandleader of the 20th century, Duke didn't really need to maintain the stride abilities he acquired as a youth. But once in a while he opened up the left hand a little bit and you could tell he played the Harlem rent parties of the 1920s, too.

This dance-band performance starts with a couple of vague choruses of stride. It's not the greatest playing Duke ever did, but it is the perfect curtain raiser for an astounding document of a classic Ellington band at its best.

0:00 Somehow I think that even Duke is uncertain what the next tune will be. He starts in the wrong key, G, and but then changes his mind and tonicizes D.

0:14 Sonny Greer, the original leader of this band, hears where Duke is going and begins checking Duke's forward momentum a little bit. "Not so quick, Duke! Sheesh, I always have to make sure you don't rush."

0:16 D major is a strange key, so the band fiddles on their horns to confirm it. Well, there's only one tune in the book in D --

0:48 Duke plays the correct piano cue that's on the studio recording. Jimmy Blanton thinks about coming in, but stops to take another drink or something. There's just a little erratic 2-beat in this chorus from Blanton, matching the 'oompah' of Duke's left hand.

1:20 Trombone choir, but also Freddy Guy comes in on rhythm guitar and Blanton (putting down his drink?) begins walking. Blanton, Greer, Guy: The beat could not be more earthy or swinging from now until the end of the performance. So far, this is my favorite Blanton performance that I've heard. As with Tatum, Blanton's undeniable virtuosity could obscure what a fabulous time player he was. Bonus: You get to hear Duke verbally control the arrangement, asking for additional choruses of Barney Bigard and Rex Stewart.

It's a superb example of early jazz's 2-beat - which is stride piano smoothly moving into a more modern 4-beat. But the continuum also runs backwards: pianists of this generation always show some echo of the 2-beat (and stride) in the modern 4, too. In fact, I can hear a left hand connected to stride in 1950s performances of Bud Powell, Al Haig, John Lewis, Thelonious Monk, Horace Silver, Herbie Nichols, Hank Jones, even Dave Brubeck.

Certainly, regardless of changing fashion and a resolutely walking bass, until the end of their careers both Ellington and Count Basie could occasionally stick some stride in there without anachronism.

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson

Erroll Garner: Frantonality

Musicians:

Erroll Garner (piano), Red Callender (bass), Nick Fatool (drums).

Composed by Erroll Garner

.Recorded: Hollywood, April 9, 1946

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

Garner's style was mostly based on a chomping 4/4 in the left hand more related to rhythm guitar than James P. Johnson. However, "Frantonality" is a clear homage to Harlem stride. It's also a relatively rare example of a Garner original besides "Misty"; the fact that it is a serious stride composition in a minor key is also fairly uncommon.

Of course, the presence of a minor key doesn't stop the endless cheer of a good Garner performance. He was the kind of musician who saw no division between 'entertainment' and 'art' in jazz. Frankly, I'm not sure the way jazz rigorously defends its 'art' turf these days is so good for the music. At any rate, both Garner and Earl Hines could be seriously considered by young players today looking for unclichéd inspiration.

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson

Donald Lambert: Anitra's Dance

Recorded: Warren, New Jersey, 1960

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

I believe this performance is technically impossible. I have heard (and now seen: YouTube! ) it many times but still refuse to accept it!

Lambert's left hand on up-tempo showpieces like "Anitra's Dance" makes me think of an old-time movie projector, flickering from still image to still image but nevertheless creating the impression of smooth motion.

Edvard Grieg's "Anitra's Dance" is a light classical staple always included in various "Best-loved Classics" anthologies found hidden away in most old piano benches. "Ragging the classics" was standard procedure for this era of pianists; Lambert's "Anitra's Dance" is surely the summit of this practice. There is a studio recording from the 1940s which is also amazing (and basically the same arrangement), but I chose this version since it seems to have more limitless fire.

Unfortunately, having a real gig like the one at the Newport Jazz Festival documented on YouTube was a rare triumph in the Lambert saga. At this point, Lambert was mostly an alcoholic barroom pianist forgotten in New Jersey with just a couple years to live. Instead of a conventional epitaph, Lambert's grave in Princeton has the musical phrase "In some secluded rendezvous" (from "Cocktails for Two") carved in granite.

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson

Thelonious Monk: Dinah

Recorded: Los Angeles, November 2, 1964

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

Monk was the consummate modernist of common-practice jazz. He was arguably the consummate historian, too. Consider:

Of his peers and followers, Monk showed the most interest in performing repertoire composed before 1930 ("Dinah" is from 1925). Pianist Herbie Nichols, in the first-ever review of Monk in 1944, wrote he would rather hear Monk play 'Boston' than anyone else. ('Boston' is more or less the left-hand 'oompah' of stride, but filled out and played by both hands behind a singer or band - Count Basie did it especially well.) Monk Plays Duke Ellington was one of the first and still one of the best tribute albums by a major jazz artist. And producer Orrin Keepnews reported that after listening to the playback of 1957's "Functional," Monk declared, "I sound just like James P. Johnson."

"Dinah" is the first, fastest and most Harlem-esqe performance contained in Solo Monk, the most stride-reliant album in Monk's discography. I wonder about two possible tributes: "Dinah"'s lyrics refer to "Carolina" - could that be James P., yet again, whose own "Carolina Shout" and "Carolina Balmoral" are key stride pieces? "Dinah" does lead off Solo Monk; I can see Monk saying, "Just to be clear, this is for James P." Also, the closing trill: Monk almost never trills otherwise, but he can't seem to stop himself from ringing that bell at the end of several striding tracks on this disc. Is that a hat tip to Fats Waller, who constantly trilled too?

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson

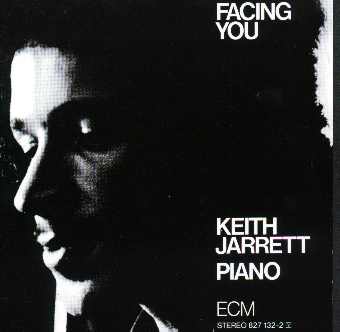

Keith Jarrett: Starbright

Recorded: Oslo, November 10, 1971

Rating: 100/100 (learn more)

Jarrett's "Starbright" is a consummate example of stride being used by a post-1950 modern jazz pianist while not sounding like a quotation, anachronism, or stunt.

"Starbright" is from the masterpiece solo recital Facing You. Right from the beginning, the spacious chords in the left hand imply something more like Earl Hines than anything else; although above, the pretty melody in sixths is quite dissonant and bitonal.

Jarrett takes half the performance to work up enough steam, but eventually lurches into a convincing left-hand "oompah" as his right hand delivers the iridescence suggested by the title. It's a major success, and one well worth considering for those looking to take stride into the 21st century.

Reviewer: Ethan Iverson