In conversation with roy hargrove

By Ted Panken

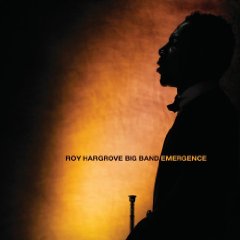

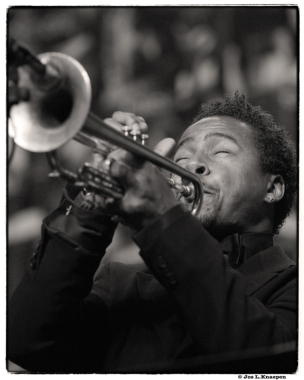

By his own account, Roy Hargrove spends about two-thirds of his time on the road. Such was the case this past summer, when in a period of seven weeks he toured all three of his bands: his quintet and big bandboth devoted to hardcore jazzand his crossover unit, the R.H. Factor. Back home in New York for a few days, Hargrove was decompressing, relaxing in the daytime, and spending his nights jamming at various New York venues: Smalls, Fat Cat, and the Zinc Bar in Manhattan, and Franks Place in Brooklyn. Still, as busy as he is, the 39-year-old trumpeter, resplendent in a pink-check jacket, shorts, and a narrow-brimmed hat, strolled into the Jazz Gallery this hot afternoon exactly on time for a discussion framed around his new recording, Emergence [EmArcy], his first with the big band.

In point of fact, Hargrove's projection of an old-school attitude toward road-warriorship, song interpretation, blues feeling, and swingwhile simultaneously tuning-in to the popular music of his time on its own termsmay be singular among hardcore mainstream-oriented jazz folk of his age group. Which of Hargroves peers of comparable visibility would embrace the requirements of playing third trumpet in the Dizzy Gillespie All-Star Big Band with as much enthusiasm as Hargrove devotes to the various ensembles that he leads? Which other highly-trained post-Boomer would deliver a lyric like "September In The Rain," a staple of Hargroves sets for at least a decade, with as much brio as Hargrove projects when uncorking cogent, thrilling solos on structures ranging from bebop to post-Woody Shaw harmonic structures? Indeed, in his ability to blend the high arts of improvisation and entertainment with equal conviction, Hargrove is a true descendent of such iconic elders as Louis Armstrong, Roy Eldridge, and Dizzy Gillespie, all musical highbrows who wore their learning lightly.

How does the big band sound now compared to when you did the record, after playing quite a number of gigs over the last year?

Its really tight. Im trying to get them to the point where they have the music memorized, and dont have to use the written music any morebeing able to play by ear is so important. When I played with Slide Hampton and the Dizzy Gillespie All-Star Big Band, I tried to memorize the parts so that I could pay attention to everything thats going on with the conducting, with the dynamics, and try to make it very musical. Its getting close.

How big is the book? There are 11 tunes on the recording?

Theres probably 30 songs or so.

In the program notes, you stated. 'I always wanted to work in a big band format. The sound is so full and rich, and it provides opportunity for congregation, which is much needed among todays younger musicians, most of who have come of age in small group settings. Im also thankful for the opportunity to exercise my compositional and arranging skills. Music is such a vast world, and I intend to explore every avenue possible. The cast of players on this project are all guys I met in school and on various gigs and jam sessions over the last twenty-odd years. I think we all share a strong passion for music that comes from the heart.'

Two themes arise which are a common thread in your career. One is this notion of congregation, communication through music, speaking across generations and styles. Also curiosity, hunger for information. I can recall watching you as a young guy getting your butt kicked by the elders at Bradleys, and not being daunted or fazed, but taking it in a constructive way and coming back for more.

True.

Now, in the liner notes, Dale Fitzgerald writes that the first day he met you, you told him that to have a big band was an aspiration. You were always interested in that notion?

Yes. I always watched Dizzys big band on video, and it was very inspirational to me. When I started to embrace playing jazz as a teenager, the big band format was my training ground, in learning how to read, and learning how to play in a section in a group. For me, its kind of going backward. Earlier, there were big bands and then they went to the small groups; now its small groups, and Im trying to bring back the big band thing.

I believe its really important that we all have to know each other when we play together. Most big bands, if its a great ensemble, the soloists are okthey have one or two. But this group is a band full of soloists, so its challenging for me to try to bring them all together and have them play where the entire ensemble is thinking in the same direction, with tight cutoffs and everybody breathing at the same timethe things that normal big bands do. A few guys work in the Broadway shows, so they have a lot of experience ... everythings by the numbers. So theres a balance between discipline and at the same time keeping it very loose and spontaneous.

You just mentioned that watching videos of Dizzy Gillespies big band was an early influence.

Yes. The way Dizzy conducted the band, and the way he seemed to have so much funand they were having fun. This was inspirational to me, and I wanted to have a group like that.

Playing with the Dizzy Gillespie All Star Big Band over the last number of years has probably been a great training ground in putting together your own group.

Oh, its been great. Especially playing in the trumpet section there, playing the third trumpet part on Slides arrangements. The third trumpet part is a kind of focal point within the band, because you get to hear all the different ensemble parts written around the voicings. A lot of times, the third trumpet part, or even the third trombone part, has special notes that make the chord grow. Im a sponge, listening to everything and taking it all in. It just gives me more information to transfer along to the group.

The program of Emergence contains many flavorsLatin, straight ballads, you sing a bit, exploratory pieces arranged by Gerald Clayton and Frank Lacy. But somehow, the template seems rooted in the mid-50s Dizzy Gillespie Big Band; the Ernie Wilkins-Quincy Jones synthesis of Dizzy and the Basie New Testament band, seems to be a jumping off point for the feeling you have in mind

Exactly.

Its a nice blend of art and entertainment.

I think that musicians should always have fun when they play. Sometimes it gets too serious. Thats just my opinion. When we play, it has to be tight, but at the same time I like to have the freedom to go outside of the box a little bit.

Talk about the process of recruiting this band.

Now, thats difficult. With a big band, theres hardly ever any money to pay guys, so its hard to get cats to be available.

It started off as a sort of Monday workshop thing, as often happens around New York ...

Actually, the first hit was about 15 years ago, in Washington Square Park, where I was able to pull together a kind of all-star thing, with Jesse Davis and Frank Lacy, and even Jerry Gonzalez in the bandJerry was playing fourth trumpet and percussion! I was able to do that first hit because the Panasonic Jazz Festival, which was running the event, paid us enough that I could give each one of those guys a grand or something. They were excited. 'Ok! You got some more gigs?' But at the same time, throughout the process, the music grabbed them, too, and here it is, fifteen years later, weve brought it back, and everybody seemed to want to be part of it.

The other thing is that there arent really any gigs out there, and there're a lot of musicians. People want to play. So it wasnt that difficult to find musicians to be in the group. But its always a different gauge to try to find people who are available. For example, we did a few things here at the Jazz Gallery, and I was trying to find trumpet players. We shifted around a few different people, but we finally got what seemed to be a lineup of ringersTania Darby, Frank Green, Greg Gisbert are all very good lead players, too, and Darren Barrett, who I went to Berklee with, is a great soloistClifford Brown-Donald Byrd stuff. I guess finding the trumpet section was the hardest part; for a while, we had some mishaps. But we managed to pull it together.

Im always at jam sessions, like I was last night, so Im always running into musicians. I just go into my mental rolodex and pull out the people I know.

It takes time to accumulate a book. How did you accumulate repertoire?

I arranged a few of my songs for it, just to begin, then I told the cats, 'If you want to write something, bring it in.' For this album, I asked Saul Rubin to write the arrangement on 'Every Time We Say Goodbye,' and I had written 'Tchipiso' and asked Gerald Clayton to do the arrangement. Then, of course, theres our theme song, 'Requiem,' by Frank Lacy, which weve been playing. Thats the chop-buster for the whole band; they like to play it, but its kind of difficult. Its very powerfully arranged.

I try to include the music that I learned when I came to New York, from cats like John Hicks, Walter Booker, Larry Willis... Right now, a friend of mine is working on an arrangement for Hicks 'After the Morning,' which we used to play at Bradleys all the time. My premise is to try to pass down the information I picked up from cats like John Hicks, Walter Booker, Clifford Jordan and Idris Muhammad when I started cutting my teeth in jazz.

Apart from the Dizzy Gillespie All Star Big Band, what other big bands have you been part of after high school?

I think thats the only group Ive actually played in. Ive sat in with a few, played with some large ensembles here and there, but not anything that happened more than once.

Playing in big bands was a rite of passage for many of the older musicians who were your heroes, who came up before 1955-1960.

Thats why I think the music needs this. It creates some kind of humility. Its very needed. Excuse me, but a lot of times, especially now, when I got to the jam sessions, people are so ego! Ill give you an example. Well play an F-blues, and everybody with an instrument will get up and play, and it goes on for three hours. Each musician will play 100 choruses. Theres no humility there. Big bands, large ensembles create an environment where you dont have to play for two hours and stretch out. Everybody cant be John Coltrane! Sometimes you can just play half a chorus. Charlie Parker will play a half chorus and blow your mind! Theres something to be said about being able to trim it downsay less but have it have more meaning.

Is that something you learned early on, playing in your high school big band?

No, I didnt learn that early on. Im still trying to learn that!

Its a quality that you aspire to.

Yes, I aspire to it. Sometimes, you have to make the amount of music that is just enough. You dont have to overcrowd it.

How do you see this band vis-a-vis other contemporary big bands? It isnt as though the scene is totally devoid of big bands, though there arent so many that work steadily.

Yes, there arent that many.

Maria Schneider, the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, the Vanguard Orchestra, the Mingus Orchestra, Carla Bley ...

My group is not quite that streamlined. Im still trying to get it to that point. My group is filled with hooligans.

No hooligans in those other bands?

No hooligans over there. Theres plenty in my group, though. My vision of that just seems like theres those groups, and theyre all very clean-cut and organized, and then theres my group, which is complete chaos. A lot of characters. Its never a dull moment around those guys. When were hanging or traveling on the train, all I have to do is go around them, and its entertainment all day.

Does the composition of the band somehow reflect your personality?

Maybe so. Ive never really thought about it like that, but yeah, probably.

So youre talking about camaraderie and the jazz culture. This band evolved through this location, the Jazz Gallery, which has served over its decade-plus ...

As a breeding ground.

... as a breeding ground and also a kind of communal space for a lot of young musicians from many different communities.

Thats right.

Talk a bit about the interface between the Jazz Gallery and the evolution of this project. Your quintet identity was already long-developed, but the big band identity not so much.

I have to give it up to Dale Fitzgerald, because it was his idea to bring this back into the picture. The first gig we did here at Jazz Gallery, people got really excited. That got the ball rolling. Then I got excited about it. I figured, well, its been over ten years; we might as well record the thing now, try to take it out on the road. I guess thats an uphill battle, considering the economy and everything else going on right now. But still, I think its very needed. The kind of conversation youll get with it is worth more than money. To me. Because it would help if we can feed jazz with something fresh. Its difficult right now. People dont want to swing any more. That dance element is getting buried, more and more and more. Its got this esoteric sound. People want to be so hip. They want to create the new thing. But the new thing, to me, is the dance. Theyve buried that. I like hearing drummers when they play the ride cymbal. You cant get drummers to play the ride cymbal any more. Theyre always playing like a drum solo throughout the whole song. The ride cymbal, that is your beat. Thats your identity. The way the bass and the drums sound together is a big deal. People just forget about that. Everybodys on their own program. Thats why Im doing this whole big band thing. Thats why Im doing all three bands. Instead of music just being in the background, music should be like therapy for people. When you go to hear music, you should feel better when you leave. Like youve been to the doctor and he heals you.

Another flavor of this band which also hearkens to Dizzy Gillespie is your embrace of Afro-Cuban rhythms on several pieces. Two things come to mind. One is that the Jazz Gallery has been an incubator for some of the most creative Cuban jazz musicians of this period ... including some of the more esoteric ones.

Excuse me!

But then also, its the place where Chucho Valdes entered the New York picture during the 90s, and the venue where you first touched base with him and gestated Crisol. Lets talk about Afro-Cuban rhythms and how they fit into your notions about swing.

It goes back to the dance thing. When I went to Cuba the first time in 96, they was partying in there! Heres people who dont have anything, they cant even go to the store and buy orange juice. Youve got to go to somebodys house to buy beer, or something to drink. They dont even have their own bathrooms. Its crazy. But when they party, when the music starts, its like a festival. They really know how to get down. This inspired me ... the possibilities exploded in my head. I owe so much to Chucho for turning me on to that world. Before that, I had no idea. Not really. Not like that, before I went down there and saw it for myself. The level of virtuosity with the musicians in Cuba is out of this world! One guy would have five different facets in his realm. For instance, you might have a trumpet player who plays congas and is also a visual artist who can dance.

When I hung out with Anga and Changuito, playing with these guys, even though they didnt speak English, I was still able to communicate with them through the music, and they showed me so many things. They showed me how to play the different rhythms based on the clave, things that inspired me .... But I didnt really get to dive into it on this album the way I wanted to. We had one percussionist. I wanted to do a bunch of overdubs, but we didnt have time to get into it the way I really wanted on the big band thing. Theres still some music floating around from the Crisol era that hasnt been released.

Did the Cuban experience have an impact on your improvising style, on the way you phrase? Is it something you can dip into, go out of? How does it play out for you?

Just being around those guys, I soaked in some of that. Ive always been into rhythm and movement. When I play, Im trying to be a part of the dance. I want the music to go into your body, the way you feel where you have to tap your foot and snap your finger, or move your head, or something. Hanging out with those guys strengthened that feeling, made it more prevalent. When I play, Im thinking about the drums the whole time, and trying to sit in to the rhythm of whatever the drummer is doing. I pay attention to the drummer always. If the drummer isnt really happening, then I cant really play. Sometimes I can, but most of the time its a struggle if at least the time is not steady.

So it isnt so much the style or whether theyre playing swing or straight eighth thats important, but the quality of the beats. Or is that not the case?

Its a combination of things. Its the steadiness of the beat and also the way it feels, like if it has an oomph behind it as opposed to it being very quiet, subdued. I prefer to play with a lot of energy. Thats why I liked having all those drums when we were doing the Latin project, because it inspires me to play with energy and force. Drums and brass just go together.

Lets segue to the R.H. Factor project, which is a much more explicit manifestation of your dance orientation.

In the beginning, I started off trying to do a tribute .... My father was a record collector. He had foresight. People used to come to our house to see what we had, so they could go and buy it. They wanted to know what the new thing was going to be, because my father would have it.

So whatever Roy Allen Hargrove was getting, thats what ...

Yeah, they used to come to our house to see what he had in his collection. Every weekend, my dad would buy two or three records, and come back home, and then two weeks later it would be a hit. He just bought what he liked, but apparently that would be what everybody else liked, toobut later. I lost him in 95. So I wanted to do a tribute to him in a way that ... He always said to me, 'I like the jazz, but when are you going to do something a little bit more contemporary, something funky?' Id say, 'Im getting to it.' He got out of here before I could do it. So I began to collect all of these recordings from my memory, out of what I knew he had. I would go out and get Herbie Hancock with Headhunters, and Earth, Wind & Fire, and George Clintonjust reeducating myself. Id always been doing little home recordings of my own original music, and I decided to take a few of them out of the archives and transfer it into a live setting, which was the beginning of R.H. Factor. We went into Electric Lady Studio for two weeks. Once the word got out that I was doing something different, all the musicians in New York started coming through!

A lot of musicians.

A lot! Im saying every day it was somebody new. Its funny how the world is small. When the word gets out, it gets out. You know how that is, here in New York. We were at Electric Lady, and the first day I couldnt find anybody. Nobody was around. I didnt have a bass player, no drummer, no nothing. It was just me and Marc Cary, trying to get it started. We had Jason Olaine calling around, trying to find us a bass player. Finally, Meshell Ndegeocello popped up and brought her drummer, Gene Lake, and thats how we got startedand the whirlwind of creativity began at that point. For two weeks, cats were just coming ... even Steve Coleman came by one day. There were some people who I actually called to come through, more mainstream entertainers like Q-Tip and DAngelo and Common, Erykah Badu. These are my friends. It was a little bit difficult to get them, but they still came through. The only problem was that the budget spiraled out of control, because there were so many musicians, and they had to pay all of them. But that first one, once it got off the ground, was a lot of fun to do. I had Bernard Wright there, and my homeboys from TexasKeith Anderson, Bobby Sparks, and Jason Thomas. Thats the nucleus of what was going on.

Just let me interrupt momentarily. Erykah Badu, Q-Tip, DAngelo, Common, were all people youd come to know during the 90s. Now, youre best known as the leader of a hardcore jazz quintet playing swing, in a milieu where the jazz police are serious.

Mmm-hmm. But I never paid attention to that.

Well, you mentioned your fathers question, 'when are you going to play something more contemporary?' That made me wonder whether there was a tipping point where you decided ...

No-no. I never was satisfied with just staying in one place with music. I get bored. I always try to keep it rounded. When I was in school at Berklee, people thought I was strange because I would hang out with the jazz guys and the R&B cats, and then just sit there and listen to the gospel choir, saying, 'they dont understand.' Because there especially I met people who got into their locked-in things. Youve got the guys that just play like Bird, then ones that just play like Coltrane. You got the guys who are strictly R&B, and they think the jazz guys are stuck up. You got the jazz guys who think the R&B guys are ignorant and cant play changes. I never really sank my teeth into being in one of those groups. When I started recording professionally, I chose to do straight-ahead jazz, because thats where my development was at the time, and I was trying to learn how to do it. I thought there was enough people trying to rap and do all that other stuff. There was enough of that at the time! Im fascinated by Clifford, Fats Navarro, and these guys who were like institutions.

It was high art.

Yeah. Im fascinated by that. Once I got locked on to that, I couldnt stop. For me, its a blessing to be able to record jazz in this day and age. So I just went with that. But then, when it came time ... Actually, it was really difficult for me to try to branch out and do something that wasnt jazz. When I make a jazz recording, no one says anything. Theyre just like, 'Ok, take three. Thank you.' Or 'maybe we need another one, just for safety.' But then, when I started branching out into something else, everybody had an opinion. Everybody wanted to try to tell me how to write the songs, how to arrange the songs, do this, do that, 'youve gotta get this singer, youve gotta get that one.' Everybody became an authority. People in the jazz world, they all think, 'Hes a bebopper, he doesnt know what hes doing; he cant play that.' But Im from the generation that hip-hop came from, so its going to come out of me, too. I mean, my favorite group was Run-DMC when I was like 13 and 14. I actually bought Kurtis Blows first album.

Did your father like hip-hop?

He had one song he liked, 'The Message' by Grandfather Flash. 'Dont push me, cause Im close ...'

In his very warm liner notes, Dale Fitzgerald writes that you started playing in an elementary school jazz ensemble in Dallas. Then people started hearing about you when you were 14-15, when you attended Booker T. Washington High School, which had a distinguished lineage stretching back to the 40s and 50s. During that time, were you working outside school? Blues bands, R&B bands, church situations?

Yeah. Once I got hit by the music bug, I couldnt stop. I wanted to do it all the time. They had to pull me out of the band room. I was the first one there, and always the last to leave. Id stay there until 5 or 6 oclock in the evening, because I loved it so much. It was also a kind of deterrent from being in the streets. People talk about South Central L.A., but South Dallas is no joke! Erykah is from South Dallas. We went to high school together. Yeah, people dont talk about South Dallas. If you picture the ghetto in South Central L.A., or Compton, which they glamorize on TV and have the gangs ... Just imagine ten times that. Its so bad, they cant even show it on TV. You go to Texas, and the ghetto is crazy. People are just crazy for no reason! I grew up around that in the 1980s, the late 80s, when a lot of gangs were beginning, and there was a lot of crack. One time my father told me I couldnt go outside after 6 oclock. So being around all that ... having music really helped. Having something to do to keep me out of the streets. Otherwise, it might have been trouble. Im thankful for that.

Did the idea of having a distinguishing voice on the trumpet come to you pretty early? Were you modeling yourself after the cats you were listening to? Did it just naturally come forth somehow?

Being in Texas, you hear blues all the time. Blues all the time. People love to listen to the blues. Every Sunday, my father and his friends would get together and play dominos, and put on Z.Z. Hill and B.B. King and Bobby Blue Bland, and listen to the blues. My grandmother and my aunts and all of them had 8-track tapes of Tyrone Davis. A lot of blues. So the blues gets in there. So when I first started learning how to improvise and took my first solo, it was based on playing the blues. My band director showed me a couple of licks ... I guess coming up in church, you learn how to project yourself emotionally through your instrument, if you play an instrument, or if you singwhatever you do. Texas is the Bible Belt. People know what that is when you go to church, and somebody sings a solo. That becomes a part of you. My grandmother put that in me when I was little. My spirituality has always been what keeps me going. Thats what is coming through.

It wasnt until I was a teenager that I started to hear people like Clifford Brown and Freddie Hubbard. Now, hearing Freddie Hubbard pretty much turned my whole life around. Clifford Brown at first, because I had never really heard jazz trumpet like that. Cliffords technique was so good that it sounded like he wasnt even playing trumpet any more. It went into like a woodwind sound almost, as though he had practiced so much and got so good that his sound went past being just a trumpetit was just music. But then, Freddie Hubbard really got me, because he had a contemporary thing in his soundit reached back to cats like Clifford and Fats Navarro and Dizzy, but it also had a thing from my fathers generation, from the 70s. I could definitely latch onto that, especially the way he played ballads. I always liked his ballad playing. Just ballads in general. I like to play the slow songs.

So I started from blues, and then I started learning bebop when I came to New York.

That was right after high school?

Well, I was in Boston for a couple of years.

Didnt you come to New York before you went to Boston?

Well, yes, I actually did, once. But it was for a competition. I was still in high school. I didnt really leave the hotel.

But before you came to Boston and New York, there were a couple of national figures who entered the picture for you a little bit, right?

Yes. Clark Terry and Wynton. When I sat in with Wynton that first time, I was really nervous. But I thought, 'Ok, youve got to step up to the plate now; youve got to deliver.' I wasnt afraid, but at the same time I was really nervous.

Is stepping up to the plate something innate in you?

Ive always enjoyed when people enjoy. When Im playing and someone is feeling good from that, Ive liked it, ever since I was little, when I first started. When I play a few notes and somebody goes, 'Yeah!' Im like, 'ok, yeah, I want to do that every time.' so yeah, step up to the plate, make it happen.

Back to R.H. Factor and the first record that came out with Common, Q-Tip, and artists like this, what was their sense of you as an instrumentalist? Were they thinking of you as a jazz player? As a common spirit? Apart from the friendship and the collegiality, what was the artistic relationship like?

Like Herbie always says, 'Im a human being first, and a musician second.' I guess theres something to be said for a doctor with a bedside manner. You have to know how to deal with people. So when I go to the more mainstream artists, I switch the way I work with them as opposed to when I work with the jazz players. In some cases, theyre used to special treatment, and you cant be so technical.

Give me a concrete example.

For instance, with Q-Tip, I put him in the booth and let him write to the track, and just have the first 8 bars, or something like that, keep looping over and over. For about an hour I left him in there by himself. He wrote to the track, then we went back in and cut it, and he did it first take.

But theres no formula. Its different with each person. It depends on their personality. With Common it was a little different. He and Erykah were dating at the time, so I had to pull him out of the studio. Finally, I got him out of there at 5 a.m. or something, and he came down. He didnt even write anything. He just improvised his thing, which was one take. I couldnt believe he did it in one, so I was like, 'Can you do that again?'and he did it again! It was great. But then I went through all of this crap with his manager, because he didnt like the improvised thing. He wanted him to write something. Im like, 'You dont understand whats going on. I wanted it to be improvised.'

Does this emphasis on bedside manner represent your attitude as a bandleader in all the different situations?

Definitely. It takes patience and forward thinking. You always have to be thinking for the other guy, thinking what hes going to do. Is he going to miss that note? Ok, is he going to come in? Ive got to count him in. Its like a juggling act sometimes, trying to ... well, not really like a juggling act; Ill take that back. What I mean is, you have to think forward, think ahead. With the big band especiallyconducting and bringing in all the different sections and whatnotyou have to always be at least two bars ahead.

I guess you have to be like when youre leading the small band, too, keeping the crowd in mind, what to play at what timegauging all those dynamics.

I mean, its not that much different from the small group to the big groups. I think that, in a way, the approach should be kind of the same. With the small group, sometimes we play the big band arrangements, pared down, which is exciting for them.

A different flavor. Changes things up.

Changes things up, yes.

So you hit New York in 1990 after two years at Berklee. Was being there helpful to you?

Yeah, definitely. Billy Pierce was there. I did my first couple of gigs with James Williams while I was there. Greg Hopkins, too. At Berklee, I was in the Dizzy Gillespie Ensemble, which is how I learned a lot of that book. Greg had some of the same arrangements, so when I got in the band with Slide, I had played a lot of the arrangements before. That helped me professionally. I already had some training, and I got a lot there, too, though I wasnt there very long. Not just from being in the school, but from being on the streets. Going to Wallys every night. I heard a lot of great music there, and I got to know some great musicians as well, like Antonio Hart, Mark Gross, Delfeayo Marsalis .... Being away from Texas was a culture shock for me, but also very enriching as far as my education in jazz.

Then you get to New York...

Then it got really deep! While I was at Berklee, I was starting to learn a little bit of some bebop, but I was really just trying to learn how to read chord changes. Ive always played by ear, from when I first started. The first trumpet player got mad at me, because I would play his part, but Id be down at the third trumpet!

I think the ear training is such a big deal, though, especially now. Were in the information age, and you can get everything at the push of a button. So musicians have to be very complete. You have to be not only good readers and be up on the technical side of playing music, but also be able to play what you hear. Thats sometimes lacking. I know a lot of musicians who can read flyshit, but if you whistle something to them, they cant play it. Ear training is a big deal.

Anyway, it got deep when I got to New York. I started sitting in with people like John Hicks. I followed John Hicks around New York for a while.

Lets paint a picture. You were around 19-20, and spending a lot of time at Bradleys, both playing bookings and sitting in. You were playing with Hicks, and you were playing with Larry Willis, and the musicians who play on the record, Family... I personally remember an occasion when you were sitting in with George Coleman and Walter Davis, Jr. on the second set, they kicked your ass, and then you came back on the last set and hung right in there. I saw similar situations transpire several times. Its kind of an old-school way of learning, but I think it says something fundamental about you.

Im very thankful, because people like George Coleman and Walter Davis taught us how to be men on the bandstandhow to be grownups. I never will forget that same night you mention, when I was playing with George and we went through the keys on 'Cherokee,' which was like a lesson on harmony and then another lesson on rhythm. Then we played 'Body and Soul,' and he started changing up the metershe played in 3 and then in 5, and then BLAM, really fast. [LAUGHS] Then he turns around to me and goes, 'You got it.' I go, 'ok. What am I going to do after all of that?' But I stuck to my guns and tried to ride it out. Man, they were so helpful to me.

Thats why I think we just need something now. Musicians need role models, something so that they can see how its done. Id glad I got a chance to see it in person. Bradleys was an institution, to me. It was like going to school. It was like your Masters. You go in there, and youre playing, and then theres Freddie Hubbard at the bar! What do you do? This is very humbling. Everything Im playing right now I owe to that whole scene.

Before I interrupted, you mentioned following John Hicks around the city, and you remarked earlier youve commissioned an arrangement of his piece 'After the Morning' for the big band. Hicks was a musician who is underappreciated in the broader scheme of things in jazz ...

Yeah, but he was a true musician's musician. My manager, Larry Clothier, told me about John in the beginning. He said, 'Youve got to hear him; he elevates off the piano. Really. He starts levitating.' When I saw him the first time, it happened! I was like, 'whoa!' So I latched on to John, and he was like my uncle. He was like family to me. His music was an influence. I was influenced by a lot of pianists as far as how I write and my approach to harmony. Theres John Hicks, then also Larry Willis, then also Ronnie Matthews, Kenny Barron, tooand James Williams, of course.

My writing was influenced mostly by James Williams and John Hicks, the use of the major seventh-sharp 11th chord. That was my favorite chord when I was in college, and I used to use it on a lot of songs. They showed me how to use that chord, and make it very melodic. Sometimes the guys in my band would get tired, because I would write them like in parallel ... 'Man, you got some more major seventh-sharp eleventh chords?' A lot of my tunes had inflections from John or James or even Larry Willis, and they still do today.

One thing that I think shone through at Bradleys was your ability to play a ballad. At 19 you could have been called an 'old soul,' but we cant really say that now, since youre turning 40 this year.

I think thats just my upbringing. Ive always gravitated towards the slower songs. Ballads have an emotional quality to me. You slow it down, and you hear everything, all the nuances .... Maybe Im a romantic as well. I guess I believe in love! I like the slow songs. I like when its broken down. Sometimes thats where the beauty is, when you bring it in the slow tempo. And I always listened to singers. Nat King Cole and Shirley Horn. Sarah Vaughan is my favorite. Of course, I owe a lot to Carmen McRae. I got to hear her live a lot, and she used to let me sit in with her all the time. Her delivery ... I heard Freddy Cole at Bradleys as well.

Theres a vocal element in my music. I try to play like a singer. I try to sing through my instrument like a vocalist would sing. Im always thinking about the lyrics. I was told by Clifford Jordan that you have to know the words of the song, because then you really understand what its about, and when you play the melody you really understand the mood youre projecting. Also, it helps your phrasing.

It sounds like there was never any generation gap for you.

Man, I have extreme respect for my elders. I believe in that. Somebody whos been on this planet longer than me, I have to respect them. Even if theyre dead wrong, Ive still got to respect them! Theres something to be said about the fact that theyve been here longer than me, and theyve survived. When it comes to musicians, it even gets deeper.

Another thing thats interesting about how Bradleys played out for you is that, because your business arrangements turned you into a leader quite quickly, it became the primary venue for your apprenticeship. You never did the sideman thing too much, if I recall correctly.

No, youre wrong about that. I did a lot of sideman things, but it wasnt anything steady. I started off playing with Frank Morgan and the Ronnie Matthews Trio, and it went from there to Clifford Jordan, Barry Harris, and Vernell Fournier, and then Charles McPherson.

Were these one-offs or were you touring with them?

I was touring with them. I would do a week here, two weeks there with different groups. Most of them were veterans, with me, the young kid, as the special guest. They were so encouraging. Whenever I showed up on the scene with my trumpet, the older guys, like Clifford Jordan, would be like, 'Man, come on and play.' Nowadays, people get very protective over the bandstand. You want to go sit in with them, its like 2 oclock in the morning, and they say, 'Were going to play a few songs, and then well invite you up.' You cant do that at 2 oclock in the morning, man! Its too late for all of that. Lets have some fun! But people get very protective. I think the reason is because theres no gigs. That creates a thing where when somebody gets a gig, even if its 2 oclock in the morning, they want to play all their original shit and they want to speak their piece.

But the older cats were very welcoming, even though I couldnt really even play changes that well. 'Hey, come on and play.' Sometimes, when I didnt want to play, theyd be like, 'Get on up here.' Like, Kenny Washington one night, we were at Bradleys, and he was playing some fast, crazy tempo. Kenny was known for playing 220! I went to go sit down, and he was like, 'Unh-uh, come back up here.' [LAUGHS] He wouldnt let me go. 'Yeah, youre getting some of this, too.'

But even if my premise is wrong that you didnt do so much sidemanning, pretty much you were leading groups from ...

I didnt have my own quintet until 93-94, with Greg Hutchinson, Marc Cary, Rodney Whitaker, and Antonio Hart. I tried to create a couple of bands before that, but nothing really stuck. I had different projects. I had one group with Walter Blanding, Chris McBride and Eric McPherson early on

Id like to talk about your development as a trumpet player over the years. What your weaknesses were, how you worked on them.

Trumpet is a beast! When I was in high school, Wynton referred me to a guy named Kerry Kent Hughes, who was a trumpet professor at Texas Christian University. He was my very first private instructor on that level. Id been studying at school, and pretty much teaching myself, for the most part. This was the first time I actually had someone who would come to my house and work with me. Man, I learned so much. I couldnt pay him. We were poor. But he did this out of his heart. He was a classical player, but he also did musicals and shows and so on, and he was very versatile. Actually, he came to the Vanguard the last time we played there, and it blew my mind, because I hadnt seen him in so long. But Kerry Hughes would come to my house every week or so, and show me little things to help me with endurance. We worked on Cichowicz flow studies and stuff like that, and also the Arban method. This really instilled in me the importance of an everyday routine on the trumpet, certain rudimental things that you do just to keep your chops up. With a hectic schedule and touring when you have to go to the airport and so on, you dont get a lot of opportunities to practice, so you have to develop a daily routine to keep your chops up. I learned a lot from him in that respect.

Ive picked up things as I go. A few years ago, I learned something called the Whisper Tone that really opened me up, helped my range a lot, helped me to be able to play more around the horn. Im still developing, trying to learn as much as I can about the trumpet. Its a beast. Dizzy says, 'It lays there in luxury, waiting for someone to pick it up, so it can mess up your head.' [LAUGHS]

Dizzy Gillespie sure messed up the heads of a lot of people. You dont hear too many who can emulate him.

I was just listening to something last night, 'Birks Works' with Milt Jackson.

At what point do you feel you got past influences?

Im still not. Im still there.

Were you transcribing trumpeters? Were you doing it more by feel?

When I was at Berklee, I had to transcribe some Fats Navarro. Jeff Stout was my teacher, and he had me transcribe a couple of Fats Navarro solos. But I never got into transcription as far as writing it down. I dont think that you get much from that. Its better if you transcribe by ear and learn it, because some things you cant really write down all the waycertain inflections and the feel that comes from someones conception. But I transcribe a lot by ear, not even really trying to. If I hear something more than three times, Ive pretty much got it memorized.

Thats a gift, to be able to do that.

Yes, I think so. Thank God for that. But its also training. Because if you listen to music all the time, which I do, then it becomes part of you. It becomes part of your breathing. Its just like drinking water or eating. I listen to music all the time. Even when Im not listening, its still in my head.

So the quintet is your longest continuous entity.

Yeah, I like the quintet format. It has everything there. I have tried some other formats, though. Thats why I like coming to the Jazz Gallery to play, because I get to do other thingslike the organ trio is fun.

Youve also paired off with other trumpeters on various gigs here. Back to the notion of camaraderie and collegiality, it seems that you like to have another voice to play off of.

Yes, I like it.

It doesnt seem that quartet would be your favorite format.

Well, it depends. With quartet, I would probably play more ballads. But its hard to play ballads now, because the young guys dont know the American Songbook. They dont know the songs. Its difficult. I go to jam sessions a lot, and when I start calling tunes, nobody knows anything. You either get 'Beatrice' or 'Inner Urge.' Thats it!

Gerald Clayton, who was your pianist for several years, has command of that ...

He does. He knows the language of it. If he doesnt know the tune, he can figure it out. For his generation, hes one of the better ones. But then, his father is John Clayton, so hes getting it honest. But I could stump him, too. He didnt know 'After the Morning.'

But in any event, youre always bringing new young musicians into the band. Is there a disconnect for you with that generation?

I miss being able to hear some music that I just cant get enough of! Ill give you an example. Just two nights ago, I went into Smalls, and we were hanging out, jam session, everythings pretty straight line, and then my friend Duane Clemons gets up and playsand I was so happy! It was like touchdown! Know what Im saying? It was like throwing a pork chop into the middle of a hunger-starved place. I felt so good just for that little bit. Man, if I could just have a little bit of that all the time. I was telling Duane that, 'Man, you should really play more, because thats food.' He was playing the real language. He was playing bebop. He was playing the real New York stuff. The real fabric of the language of the music. When you hear it, you know what it is.

You do some workshops and clinics, too. Youre in touch with younger musicians.

Sometimes. I did a thing with Roy Haynes at Harvard not too long ago. It was real cool.

What do you think is alienating musicians from that way of playing? Is it lack of information, or ...

Lack of information.

... is it attitude?

Its both, One feeds the other. First of all, I think people sometimes come into the arts for the wrong reason nowbecause they want to be famous and rich and have a nice life, instead of trying to reach peoples consciousness and make a difference. Doing something for someone else besides yourself. People come into this, and, 'Yeah, I want to be rich, I want to have a car, I want to have people waiting on me,' and so on. It gets weird when thats your main focus. So you get the jazz musician who learned how to play in school who already thinks hes learned it all. I like to meet musicians like that, because then I like to challenge them. Thats why I started this big band. I wanted to challenge the peacocks, musicians who think, 'Oh yeah, I already know everything.' But you dont!

They dont get it. But if you love this music, youll go out and find what you need. Thats one thing I like about Jonathan Batiste, the new piano player whos been playing with me. He seeks out cats like Kenny Barron and Hank Jones. Thats different than the guys in his generation, who are more into McCoy and HerbieJonathan checks out the real thing. I have to say, he did a great job on this last tour. I was really excited, because he came out and took care of business. This cat played in all three groups.

Jonathan Batiste is out of New Orleans.

New Orleans. What are they feeding them down there?! I dont understand. Them New Orleans piano players. I had two of them in the past months, Sullivan Fortner and then Jonathan, and these guys are so complete. There was nothing I couldnt throw at them. Ive been working towards having the type of group where if I wanted to show them a new song, I could sit down at the piano and play it, and then theyd hear itI dont have to write it out or anything. Now is the first time Ive ever had a group like that; with Jonathan, I could sit down and play it once, and hed pick it up. Something about New Orleans.

So the present group is either Sullivan Fortner or Jonathan Batiste on piano...

Yes. Amin Salim is playing bass. Montez Coleman is on drums. Justin Robinson on alto saxophone.

Is the quintet a more open-ended format for you than the big band or R.H. Factor?

'Open-ended.' What do you mean?

In your current bio sheet, you remark about the big band, 'Theres not much left to chance.'

Yes. With the quintet, its always up in the air. The book is so vast with the quintet right now (excluding the new members, like Amin Saleem, who doesnt know the whole book yetbut hes learning it) that we can go in any direction you want. I can actually do the Big Band and R.H. Factor set with them, too. This version of the quintet is probably one of the more versatile units Ive had. When we play the Latin thing, its real Latin. When we play some funk, its real funky. When we play straight-ahead, its tippin. We can go anywhere. Thats basically my whole premise. I believe in variety, and also I believe in spontaneity. Theres no rule book. As soon as it starts to get to be in a rut, then I change it right away. With the quintet, we never play the same thing. Each night I try to change up the repertoire a bit so that everyone stays focused. We never get bored.

Being a bandleader is very interesting and challenging in that way. You have to keep everybody focused, and also motivated. Even outside of the music, trying to keep morale up is a balancing act as well. When youre on the road and nobodys slept for a few days, people get tired of looking at each other and it gets real dark. So I try to keep a very positive energy around everyone, so we keep it going.

You yourself must get tired, too.

Yes. I get tired. But Im ok. My spirituality is what keeps me going, for sure.

Ted Panken interviewed Roy Hargrove on August 11, 2009.

Tags:

Comments are closed.