In conversation with john surman

by Robert Lewis

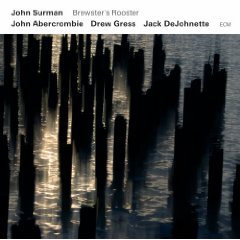

British saxophonist and composer John Surman made a couple of rare appearances in the U.S. this summer fronting an all-star quartet with John Abercrombie, Drew Gress and Jack DeJohnette, the same group of heavy hitters on his latest release, Brewsters Rooster (ECM). The 65 year-old Surman spent an afternoon in Washington D.C. talking about the obstacles that European musicians face in America, the recession and subsidies, his approach to composition and improvisation, and one of his worst saxophone nightmares.

This is your first time in the U.S. with your own band. Why did it take so long?

This may be a complicated story, but in truth its not that easy to work in America as a European musician. Work permits are difficult to obtain. You have to prove that theres something very special about you, which perhaps after 40 years in the business is not difficult for me. But there are stumbling blocks. It costs money and the whole business of working in the States depends on having a persona in America. And quite frankly, Ive singularly failed to get that persona, for one reason or another.

Is that a conscious choice?

Not at all. Ive spent much of my working life working with American musicians, but always in Europe. As John Abercrombie said many years ago, 'Im a commuter; I live in America but I work in Europe.' And Ive always worked in Europe so theres not been a lot of temptation to work in America. I did, at one point, after my colleagues John McLaughlin and Dave Holland came over here in the late 60s, it crossed my mind and I stayed for a while in Woodstock, not far from Jack [DeJohnette]. And I did a few gigs with Jacks band, but he said theres not much happening here. And then work came up in Europe and I went back and I had a house and then a wife and a family.

You are living in Oslo now?

I live in Oslo now for family reasons, just for the last 5 years. Most of my life Ive lived in England.

Whats the difference living in Oslo in terms of quality of life?

Between Norway and England? Its further north so the difference is climatic, as much as anything. And its a little more expensive to live thereeating out and drinking out and all that. But of course there are lots of social benefits.

Are you able to take advantage of their artist subsidies, or is that only for citizens?

Theoretically, I will be. Thats a very important part of their music process. The investment in Norwegian artists is vital to their culture.

Were you able to get subsidies from the British Council?

It can happen. The British Council does support certain activities and Ive benefited from that, but not in the U.S., mainly because the British Council is promoting the English language. So youre tending to get opportunities to work in places like Eastern EuropeRussia, Ukraine, Romaniabut not in the U.S.

To what extent do subsidies and government support for the arts impact the quality of the music itself?

Ill be honest with you; I share your doubts. I think it slants the market a bit. I think youll find, for example, in Europe that certain German musicians are rather upset at the fact that their Norwegian colleagues can work at clubs in Germany and can afford to do so because they get travel assistance and they even get working grants for the group. So subsidies always create an imbalance. We wont even talk about the common market and the agricultural policy and the anger between the British and the French about French agricultural subsidies, but all this political stuff is there in the music in the same way. Its slanted.

In Norway, it doesnt hurt that they have oil money.

Listen, Norway changed when they discovered oil. Prior to that they were a country that relied on fishing and farming. It was not a rich country. They were the poor relation to Sweden. Now the boot is very firmly on the other foot.

Theres been such a strong music scene in Norway for the last 15 years. Is that directly attributed to the money thats now being set aside for the arts?

I think you have to point your finger at ECM Records for a lot of exposure that the Norwegian musicians had. Prior to Manfreds excursions into Norway, Karin Krogand I have to say I have a vested interest because Karin is what you would call my life partner, my wifeshe was one of the few Norwegian jazz artists who had made it internationally. But once Manfred came in and worked with Jan Garbarek and Terje Rypdal and Arild Andersen and Jon Christensen, it helped launch this wave of interest in Norwegian music.

The compositions on the new record, with the exception of two tracks, are all original. Were they written with these specific players in mind?

Some were and some werent. My thinking was that this was an opportunity to work with three musicians who were basically very experienced improvisers working on different projects with different people. So what I thought was necessary was to create a few pieces that would create an area to work in but wouldnt be limiting. Theres no suggestion on my part that Im trying to form a tight band with hot arrangements. I just wanted to come up with some things that would be inspirational and open enough that we could get together for an afternoon, look at a few pieces, pick out half a dozen of them that would work well and go ahead and do it. So I wrote some stuff, 'Hilltop Dancer,' 'Brewsters Rooster,' and 'Counter Measures,' and then I picked a few pieces like 'Burton' and 'No Finesse' that Ive used with a rhythm section and just said, 'Lets play.'

Did you produce the record? I dont see a producers credit on it.

Basically, yes. Manfred was ill, I think he broke his arm just before the recording was made, and then when it came to the mixing he said if Jack is there, you and Jack might as well mix it. Ive known Manfred for a good many years and I guess he trusted me [chuckles].

How does a project like this come about? Do you make a proposal to Manfred?

From my point of view its worked both ways over the years. Sometimes Manfred comes to me and says its about time we did another album. What do you feel like doing? In this case I was doing a recording with an organist Howard Moody called Rain in the Window. Manfred was there and he said maybe the next project should be done in New York, basically a jazz album. And I said yes, Im ready for that. He asked me who I wanted, and I knew Jack was an obvious choice cause weve been mates for a long time. And John Ive known for a long timetoured and recorded with him a bit. Drews name came up because Jack said to me years ago that Id like him and might want to use him sometime. I bumped into him a couple years ago at the London Jazz Festival, he was playing with Uri Caine and we were both doing projects with the BBC Concert Orchestra.

How would you describe the musical personality of each of these guys?

With Jack, I especially admire the fact that hes extremely open to a wide variety of music. Hes adventurous and he has a broad palate of musical interests. The music can go anywhere with Jack. I hear in Johns playing that same sort of curiosity, that mix of fusion and country blues and straightforward jazz. He has his own sound but Im never quite sure what hes going to do next, and I love that aspect of his playing. Drew is my newest friend. I hope he wont be offended if I say his style of playing is more like Sam Jones, an older, digging-in kind of playing.

I think hell take it as a compliment.

Its that kind of strong playing, the Ray Brown-Sam Jones school. Yet hes got great arco technique and a sophisticated ear. Theres a lot about Drew Im finding out. Hes a shy man but hes a powerhouse to play with.

When it comes to composition, how much of your approach is discipline and how much is inspiration?

First, you get the inspiration, which may be big or may be small. Or you may get the deadline. Then comes the hard work. If we talk about some of the things Ive done with string quintets where theres a lot more writing than a quartet like this, then you can have the idea but youve still got to bash it out. Youve got to form it and find a way to make it work. Its a mixture of the two. You probably find the same as a journalist when you start to write something, the piece itself takes on a life of its own. So very often I find that if Ive got a commission, the house is never cleaner than before I start. You do anything to avoid writing that first note because every blooming idea you come up with seems to be trivial. But in the end you start out with something where you say this is the best I can come up with. And once you get into it, then suddenly it takes on a life of its own.

How do you transition from avoiding to jumping in?

Horror, panic, fear, the danger of not actually coming up with it; Its the brick wall technique, you just run up against it. If youre going to write, youve just got to start. So you stall as long as you can but it comes to a point when either youve got to get on with it or its not gonna happen. Im scared to death of not coming up with stuff, but I havent missed a deadline yet. If youre a dreamer, the fantasies can go on for a long time. But its hardcore when youve got to put them down on paper. Thats why at school I was never that good at writing compositions. I always had great ideas but I never really managed to find time to get them down on paper, or my hand ached by the bottom of the second page.

We dont live or work in isolation. The world goes on around us. Has the recession or the downturn in the record business had any impact on your music or your career?

I honestly think that this particular recession has yet to really bite in terms of the working process in Europe. I think were about to see it. Weve bridged over it because the work was set up before the stuff happened at the beginning of the year. There have been one or two cancellations. I know some things have gone down but they mostly carried on. And in the summer months the festival circuit has kept things buoyant. But I think the cutbacks are going to happen when the autumn planning for next year starts.

How will musicians deal with that?

With difficulty. I think it will be tough. We spoke earlier about subsidies and the fact that some countries are subsidizing artists. Its really going make a difference. If they continue to do it, then the non-subsidized folks are going to be in real trouble. So I think it will cause difficulties, though it hasnt impinged on me a great deal, as yet.

Whats the best thing about playing the saxophone?

Its a very vocal instrument. My introduction to music was singing as a choirboy. I was a boy soprano and a soloist. But when the voice changed I missed that.

Your favorite choral works?

Bachs St. Matthew Passion. First time I heard that with full chorus and orchestra I must have been eight or nine. I couldnt sit still. I didnt know what to do with myself.

So then your voice broke?

Yes, so I suspect its that vocal quality that I like about the saxophone. But I have to say I dont think my choice of instrument was dictated in any way by any prior knowledge of what riches I would find there. I bought the clarinet because it was very cheap in a pawnshop and Id heard some traditional jazz. I said thats fun; Ill get a clarinet. It was only seeing a baritone in a shop window next to an alto for 37 pounds, 50 shillings when I was 16 that led me to the saxophone.

Can you say what you liked about that baritone in the shop window?

It was big and golden and wonderful. I was privileged to interview Sonny Rollins some years ago and he shared the same story, when his uncle opened the case with red velvet inside and then the golden horn. Ive always has a passion for instruments because aesthetically I think theyve beautiful; French horns harps, violins, theyre beautiful things to look at. So I picked up the baritone and got down to low C and my whole body vibrated and I said I want this.

Was there much music around your house?

Yes, my dad was an amateur pianist who would accompany singers in what they used to call concert parties. He loved to play and he could hack his way through some of the Beethoven sonatas. And the radio was on a lot, the basic classical music repertoire. The BBC was very pompous in those days; the announcers sounded like they wore black tie on the evening program. And you got the full symphony, not just a single movement. Anyway, there was lots of music around, especially birthdays and Christmas always around the piano.

What was your first exposure to jazz?

That would have been the traditional jazz revival when I was about 15. So that would have been in about 1958 or 59. And skiffle became quite popular on the radio at that time, and that really grabbed me. I got the clarinet and I found my way to the local jazz club, which was on Friday nights in the Virginia House Temperance Hall. And I stood in the corner backstage and played along with the band until eventually after about a few months the clarinet player said come on out and play. And that was it.

Did you ever memorize solos or transcribe things?

No. I was never into copying, and I didnt have the technique at the time to transcribe.

So when did you start composing?

I always wrote little pieces. But I didnt really start until I was in London in college. At the music college the teaching was so dead and so hidebound and so full of rules that I was put off, scared to write because of breaking the rules. So composition emerged slowly. I was playing more at the beginning of my career than writing. I dont think I got really into writing until the 70s.

How did you learn to improvise, and how would you teach someone to improvise?

You improvise by doing it. You play along with records. In my case, I just played things that I tried to fit in, rather than to play what anyone else played. So I would have begun with Armstrongs Hot Five recordings. Theyre not complex harmonically, so youve got time to find the right notes. For people who want to learn to improvise, I find its handy if you can play the instrument a bit first. But given that, its just to do it and not feel too hidebound by restrictions and rules. If you really want to improvise, Im someone who advocates a lot of use of the ear, and you can refer to the paper afterward.

We all know classical players who know their instruments inside and out and they can read flyspecks in front of them, but they dont have a clue how to improvise.

And they get very tense and very nervous and theyre really awfully afraid of making a fool of themselves when you ask them to try. What I do is give them a different instrument. A recorder or a little keyboard or something, then you dont have the fear of making a fool of yourself on this instrument that youve been practicing eight hours a day. And then they can have fun with it and you say, 'now try it on your instrument.'

Back to composition, when youre working on a piece, how do you know when youre done? Do you constantly revise or edit?

Well, one thing is when I get bored with it, then I think to myself, thats enough, mate. But you can always tinker with these things. And if I have time, Ill get to the point where its almost done and Ill leave it, then come back to it later with fresh ears. Very often the process is more about combing out stuff than putting it in.

Do these ideas ever come to you fully formed?

In the jazz form youre dealing with a sequence and sometimes Ill get that. But if you want to turn it into a composition, theres more to develop it. So up to a point, I can get a vision of what it might be. Theres an architectural feeling about a composition, but I dont think I know what it is until I hear and see it.

Are you ever tempted to go back later and revise a work?

Ive got boxes full of bits and pieces, which are the first source when it comes to writing the new thingunfinished ideas, little bits that dont seem to go anywhere, or things that were tossed away are all source material. So if Im thinking, 'what the hell am I going to write now?,' Ill dig around in the box. Im a great keeper of scraps of paper from 40 years.

Do you ever hear music in your dreams?

I dont really remember dreams very much except the horror things that wake me up in the middle of the night, like youve got to the gig and theres no mouthpiece in your saxophone case.

Has that ever happened?

Not yet. But last night my baritone broke in the middle of the first set. These nightmares can occur. It was a rod that broke loose and a whole stack of keys lifted. So nothing would close from halfway down. Luckily my son was there and he plays the saxophone and discovered what the problem was. Happily, I had another instrument [soprano saxophone] with me.

Whats your general attitude towards practice?

It used to be very casual. When I was starting to play I rarely practiced. But thats because I was playing all the time. If there were any places to play, Id go there. But I find that I work out on the horns more than I used to. Its a physical thing. When youre in you 60s, your body doesnt repair as easily. So if Im out of practice in the embouchure, and if I have to play with powerful players seven or eight nights in a row and Im not prepared, then Ill be dealing with cuts and blood. So its a physical thing now.

Is there a British style of jazz?

I honestly dont know. Ive always felt that jazz, in a way, is about individuals. Let me try to codify this, because this question comes up fairly frequently. Lets not be surprised that there are different styles. But most of the younger generation players that I hear now are really playing retro jazz from different eras, so I dont hear a particular British-ness about it. I suspect that for players like John and maybe even Jack, the broadness of the scope of the European scene has enabled them to spread their wings. Maybe the openness of the European scene has been helpful to those American musicians who wanted to expand their horizons. Talking to my son, whos a sound engineer for Scofield and works a lot in America, he thinks that American audiences tend to be a bit more conservative. Jazz is a little more in a box here. He thinks theres more of a broader range in Europe. I dont really know if theres a British school. But I grew up on the English national songbook before I got into this fantastic American art form. And it was jazz music that liberated me, that gave me a wonderful opportunity to make music. So I think Im a jazz musician, not a British jazz musician. I just play.

In what way did jazz liberate you?

A musical career in classical music would have been a straitjacket for me. But this gave me an opportunity to break all the rules and do all the things you werent supposed to do in music. It was jazz that gave this fantastic chance to find my own music. And it gave me a chance to be a composer, although I hate the word.

Why?

To me, Stravinsky is a composer. Bartok is a composer, not me.

Do you think it is human nature to break rules or to follow them?

[long pause] Thats a bloody good question. I honestly dont know. Christ. I suppose when its convenient we follow the rules but if we dont like them we break them [laughs]. Its a blend. Sometimes I find that the rules are there for a damn good reason. They make living life possiblecertain rules, if you know what I mean. They save you a lot of time.

Youve worked as both leader and sideman. What do you think makes a good leader?

I think vision and understanding of the people youre working with. People like Gil [Evans], who I admired and had a wonderful time with, for me it wasnt what he did on the bandstand, it was just that feeling of excitement that everyone had when Gil came because you respected Gil. If someone lost his wallet, Gil was the first one to reach into his pocket for money to help out. He looked after the musicians. He had a sense for who they were and he gave them the freedom to be themselves, and he also had a paternal thing about him too. There are others whove ruled with a rod of iron, but the ones that I enjoyed working with were compassionate people.

And how would you describe your style of leading?

Loose [laughter]. I just try and lead by example.

Is there enough work for you?

Im happy to say there is. Ive never had a problem about work, but Ive never wanted to work all the time. Im not that kind of person. Im not a workaholic at all. I find that I refresh better with breaks. I dont like being on the road all the time. I did a lot of it when I was younger, touring in Europe constantly starting in the mid-'60s, and then the '70s with the Paris Opera working in music and dance. Into the 80s I did tours with Miroslav [Vitous] and Paul Bley. But now being on the road is harder, especially flying with your instruments and having them damaged.

Your record came out but youre only doing two hits here in the U.S., in Washington and New York.

There are two issues there. First, Jack, John and Drew are busy. And I never intended for this to be a working band, not at all. Im absolutely amazed that were doing these gigs. I thought wed make the album and then do something at the London Jazz Festival. But to work like this with this quartet is a surprise.

Several times youve talked about how your music doesnt always fit into a box. How have you resisted the temptation to conform, to fit yourself into a box? Wouldnt it have been much easier?

Yeah, it would. There are so many terrible moves Ive made, like with synthesizers.

Why was that a terrible move?

Because at the time I did it, the jazz people, particularly in Europe, didnt want to know about synthesizers and electronics. That wasnt the thing at the time. The pure jazz was acoustic. But I liked synthesizers and still do. Its just another instrument. It would have been easier to conform but it wouldnt have been as much fun. For me, if I stop enjoying this music, Ill go and teach school or dig a garden or get a farming job. The music means a lot to me. I feel something when I play and I want to keep it that way. I dont want to be dead inside and play music and be forced to do something I dont want to do. Ive been blessed because Ive survived. And part of the reason Ive survived is because Im reasonably versatile. Im not a bad reader, and I can hack it as a baritone player in a band. I play a variety of instruments and I can be part of ensembles that play Dowland and Medieval music. And I can be part of the Anouar Brahem and Dave Holland project because Im interested in Middle Eastern music. And I play bass clarinet, which fits into all sorts of weird music, so I think versatility helps. And I can write.

As a musician and composer, how do you measure the success of your work?

I measure my success by the fact that Im still invited to play with some fantastic musicians. And they seem to get on with me.

Larry Appelbaum spoke with John Surman on Aug. 29, 2009.

Tags:

Comments are closed.