The Jazz.com Blog

October 19, 2008 · 3 comments

Remembering Neal Hefti

A few days ago, when the media reported on the death of composer and arranger Neal Hefti, they focused on his popular themes to Batman and The Odd Couple. But knowledgeable fans realize that there was a lot more to Hefti than his work for the small screen. He was one of the most distinctive big band writers of his generation, and possessed an uncanny knack for creating swinging charts that appealed to both jazz devotees and the general public. Jeff Sultanof offers his reminisces and insights in his tribute below to the late composer. T.G.

Neal Hefti, who passed away on October 11, is one of the more interesting American musical figures involved with jazz. Known by the general public more for his themes for Batman and The Odd Couple, Neal was very happy that he'd captured the imagination of the public at large. In fact, in 1950, Hefti deliberately changed the direction of his music "so that Johnny next door can play it." His tune "Coral Reef" was a pop instrumental for big band, which tuned out to be a big hit. This and other popular singles on the Coral label helped to launch his own big band featuring his wife Frances Wayne as vocalist, which was hardly a jazz unit.

And yet, when Hefti was involved in a jazz project in later years, the results were magical. Clifford Brown with Strings is generally believed to be the best album of a jazz soloist with a string section, although there have been many such excellent projects since. By any measure, this album is one of the most influential and beloved in the jazz canon.

I've never seen the following information anywhere, and yet Derek Boulton, owner of the Horatio Nelson label, and manager of Robert Farnon and the Ted Heath Orchestra (among his many clients), swore to me that this is true: Neal Hefti's original last name was Frieberger, and he and his brother John were adopted by a family named Hefti because his birth parents were too poor to take care of them. "I call him Uncle Frieberger," Derek told me when I saw him in the mid-eighties at a luncheon honoring Farnon. One of the few gigs Neal did after the seventies was a concert with the BBC Orchestra, which Boulton made happen. Boulton is a persistent man, and must have bugged Neal unmercifully, as Neal had pretty much retired by 1980.

I met Neal over the phone in the mid-eighties when I was a standards and jazz editor at Warner Bros. Publications. WB had just purchased his catalog and my bosses were looking for opportunities to use it. The first thing they did was put back in print the big band arrangements all of us had played in our school music programs, and these titles are still popular"Lil' Darlin'," "Cute," "Teddy the Toad," "Why Not?" "Sure Thing" and quite a few additional titles. They also wanted a Neal Hefti songbook, and I was asked to call him. Neal was pleasant but our initial conversations were very business-like and to-the-point. Over time, I started dropping some hints that I knew his music well, and that so much of it had influenced my musical life. Finally, he said with bemusement, "Are you some sort of historian?" That seemed to break the ice a bit.

His first professional arrangements were written while he was still in high school, and they were for top unitsNat Towles had one of the finest territory bands of the big band era, but his reluctance to record and to play big cities has robbed us of any evidence of his band save the memories of the musicians who played in it, who included T-Bone Walker and Billy Mitchell. Earl Hines also bought some work from Hefti at this time. Neal played with Bob Astor, Charlie Barnet, Charlie Spivak and Horace Heidt before he joined Woody Herman, who was in the midst of modernizing the style of his band. With Ralph Burns, Hefti turned the band's music around, arranging such titles as "Let it Snow, Let it Snow, Let it Snow," a new version of "Woodchopper's Ball," and composing originals such as "Wild Root" and "The Good Earth."

Hefti married the vocalist with Herman, Chiarina Bertocci, better known as Frances Wayne, and left the band in 1946 to free-lance. His arrangements were soon part of the Buddy Rich book. He made a few records for Keynote (including a Wayne vocal of "Siboney" which was not released at the time; Neal was delighted when it finally came out in a complete Keynote boxed set), joined Harry James as a trumpeter/arranger, and then wrote for Tommy Dorsey. One of the most pleasant surprises I had in recent years was discovering a Hefti arrangement of "La Rosita" written for the Tex Beneke band some years after Tex disassociated himself from the Miller ghost band. It is a beautiful, exciting, stunning piece of writing.

Any listing of his work as a composer would be incomplete without mentioning a recording with Charlie Parker called "Repetition." The story is well known; Neal wrote the piece without a solo, Parker walked in during the session, Norman Granz asked if he could be included, and Parker tossed off a solo which can only be described as incredible. How many musicians, irrespective of instrument, can either play or sing a solo of this caliber at a moment's notice?

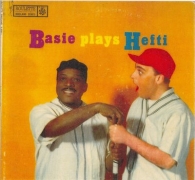

And then Neal turned his back on the music he was known for. Perhaps not wanting to be stereotyped as a jazz composer/arranger, he simplified his style. He wanted a larger audience for his work, and I'm sure the possible financial rewards were not far from his mind. "Coral Reef" signaled his being a new artist for the new label Coral Records, and for several years, he wrote catchy melodies which audiences enjoyed and remembered. This led to jingle work, arranging for television and radio, and an association with Count Basie which helped both of them considerably. Listeners worldwide enjoyed "Cute," "Flight of the Foo Birds," "A Little Tempo, Please, and L'il Darlin.'" While the Basie musicians preferred the music of Thad Jones, Frank Foster and Ernie Wilkins, they knew that Hefti's music helped to introduce the band's sound to a wider audience. To this day, a Basie performance is not complete without one of Neal's pieces. Many of his Basie pieces had lyrics added later by Steve Allen, who sang these songs on his television show.

When his catalog was purchased, Warner Bros. was able to get piano/vocal arrangements of most of his well-known pieces, which made my job much easier. Neal and I reviewed them together and corrected them, I wound up arranging some titles which had never been in print beforea project that proved to be extremely successful. Many music lovers hadn't realized that the composer of "Batman" and "The Odd Couple" had a full, rich musical life before these themes were composed. I commented that so many of his works were unknown or unavailable, and asked if he would consider preparing a fakebook of them. He was thrilled with the idea.

Now came an adventure. Neal told me that he'd thrown out all of the music he'd written over the years. After getting over the shock, I listened as he explained that sometime in 1976, Frances was diagnosed with incurable cancer. She disliked Hollywood and wanted to be with her family in Massachusetts. Neal simply thought that his wife was more important than any of the music he'd written, and that was that. When Frances died, Neal moved back to California, and was now anxious to get his music straightened out so that if people wanted to play and arrange it, there would be accurate sources from the composer. Neal contacted the Library of Congress and got copies of whatever lead sheets they had, rewrote some of them so that they would lie in comfortable keys (he was always thinking of the student or amateur) and sent them on to me.

There were surprises. A lead sheet came in for an instrumental named "Great Moment." According to the discographies, Ed Finckel wrote this for Buddy Rich. I brought this up to Neal. "No, this is my tune, he explained. Buddy rehearsed it at the Earle Theatre in Philadelphia." So not only could I get this in print, I could correct a long-standing discographical error.

"Neal, when was the last time you heard this?"

"When Buddy played it in 1946. He never recorded it, but you already know that."

"What if I tell you that there is an aircheck of it on a bootleg LP? Would you like to hear it again?"

"OF COURSE. When can you send it?"

It's nice when you can be the person to unite a composer with one of his pieces that he'd long forgotten. It turns out he was more than happy when he finally heard it.

During our work together, it was inevitable that other facts would come up about Neal's work. He never authorized the Jon Hendricks lyrics to "L'il Darlin'" and was quite angry that Hendricks didn't ask him for permission; he added that the Bart Howard lyrics were authorized although not as well known (the lyricized version of the song is called "Don't Dream of Anybody But Me"). He did not include "Rhumbacito" in the fakebook because he admitted that it was very close to a theme for a movie written by Alfred Newman ("We played so many theatres and heard these themes over and over. I don't want to make a bad situation worse."), that his tune "Better Have Four" for Harry James was a punch line to a dirty joke, and that he'd wished he was more careful with titling some of his music, and that he hated his arrangement of "In Veradero" for Stan Kenton and was quite upset with me when I transcribed it for the songbook (it was soon replaced).

He also discussed his career with me. After leaving Coral Records, he signed with Label X, an RCA subsidiary that lasted for about three years. One album was a 10" collection of themes written by Rudolph Friml. In these recordings, Neal used a wordless chorus, which he would do in subsequent albums. But it was Ray Conniff who was credited with the idea when "'S Wonderful came out, and Neal was quick to tell that he did this first. He was happy that his collaboration with Clifford Brown was as popular as when he made it. He had no insider stories to tell about this project: he loved Clifford, Clifford loved him, everything went smoothly (it shows on the album).

In the early sixties, Hefti took his wife and two children out to California to work in the film industry. He arranged an album for Count Basie and Frank Sinatra without getting cover credit, but Sinatra told him he could make an album of his own. Jazz Pops has recently been reissued, and it is worth having. It reminds us that Hefti was still a superior arranger of jazz materials. The album has the standard saxes and brass, and includes a four-man flute section. This sound would be all over movie soundtracks during the mid-sixties, and Hefti anticipated the popularity of the sound just like Henry Mancini made the French Horn section popular when he wrote "Peter Gunn."

Like Mancini, Neal's themes were bringing in money, and he could pick and choose his projects. He turned down arranging work for singers, not wanting to write twelve arrangements in two days as was customary in that world. His soundtrack for the 1964 movie Harlow yielded "Girl Talk," which was adopted for the theme for the Virginia Graham mid-day talk show. "Lonely Girl," the theme from the movie, was one of Neal's loveliest melodies and deserves to be more known.

Ironically, it was the success of his music for Batman and The Odd Couple that led to Neal giving up writing. When I suggested that he write music simply for himself, he laughed. Except for teaching film scoring at USC, he was through with music, except taking care of what he'd already written. Losing his wife in 1978 was not tragedy enough, unfortunately; cancer took the life of his daughter in 1997.

In many ways, Hefti's career was fortunate. Like Mancini, he understood the public and gave it music that they embraced. Sometimes he was able to really stretch out and show the depth of his considerable talent. It would be tempting to think of what he would have done given a large budget and a big band for an album project.

He left his mark on the jazz world, and was a very nice guy. I don't think you can do much better than that. I shall miss him a lot.

This blog entry posted by Jeff Sultanof

Tags:

I really enjoy this kind of personal reminiscence; the people we admire are more than just names on record labels, and it's always nice to get to know them a little. And I had forgotten completely about the Keynote tracks. Thanks, Jeff.

Neal's Li'l Darlin is one of my favourite numbers for my own live performances and is on our latest CD with the fab Bob Cutting playing the lead. Neal was pure brilliance, he was also a big favourite of my dad who played probably more of Hefti than I do now in our show and so I grew up listening to this great mans arrangements on the road with my dad. I liked his diversity and he was clearly not afraid to stretch out into other areas! We'll be playing him for a long time yet!

Thank you Jeff, courtesy Google and Jazz.com, for your beautifully presented 'eulogy'. I am a 70 year old Aussie and former drummer who, for the last 20 years or so, has derived so much pleasure from working hard at 'reading the dots', playing the piano and, ever so slowly, reproducing some of the wonderful tunes created by the masters. That is how I belatedly discovered Neal Hefti's God-given talent for composing and arranging. (Oscar Peterson had previously drawn my attention to 'Li'l Darlin' and 'Cute' but Neal Hefti's name was news to me at the time.) I have a couple of good publications on the musicians but is there a similar publication available which covers the lives of the best jazz composers and arrangers of the 20th century?