The Jazz.com Blog

October 21, 2008 · 0 comments

Ornette: The Blue Note Years

Ornette Coleman's stint as a Blue Note recording artist was short-lived, and his recordings for the label often given less attention than his earlier Atlantic and Contemporary releases. Yet they represent some of the most provocative music of the era. Below is the first installment of Chris Kelsey's two part article on this fertile period in Coleman's career. For part two, click here. T.G.

In 1963, Ornette Coleman dropped off the face of the earth.

No, he wasn't abducted by aliens or snatched from the streets of New York by some Free Jazz-hating cult deprogrammer. His family and friends knew where to find him. But after knocking the jazz world on its posterior beginning in 1959 with such epochal albums as The Shape of Jazz to Come and Change of the Century, the man whom Modern Jazz Quartet pianist John Lewis labeled "the most important jazz musician since Charlie Parker" (and whom the noted authority on aberrant psychology Miles Davis diagnosed as "all screwed-up inside") unexpectedly and voluntarily withdrew from the scene.

As with most things Ornette, the reasons for his mini retirement were obscure. Controversy surrounding his music and a shortage of gigs were likely factors. So was money. Ornette never thought he was paid enough. In any case, after a self-produced concert at New York's Town Hall in December 1962, Ornette would not record or perform in public for more than two years.

Nobody as compulsively creative as Ornette could just sit on his hands for two years. Like Sonny Rollins, whose celebrated 1959-1962 "retirement" remains jazz's most celebrated disappearing act, Coleman spent his hiatus in the woodshed, further honing his saxophone chops and composing new material. More than that, he taught himself two new instruments: trumpet and violin. By the time Ornette reemerged in January 1965 with a successful run at New York's Village Vanguard, he was a new and improved jazz provocateur. The Vanguard gig began a yearlong stretch of activity that culminated in a November/December engagement at the Gyllende Cirklen—the Golden Circle, in Stockholm, Sweden.

Blue Note Records had been interested in Ornette since at least the Town Hall concert, which it had recorded but never released (ESP-Disk eventually issued the LP). When it became clear his comeback had legs, the label stepped in and taped him at the Golden Circle, thus beginning a relationship between the Rolls Royce of jazz labels and the music's most provocative and influential artist.

While Blue Note is rightfully known for its devotion to hard bop, it also played an essential role in recording the '60s avant-garde. The company had begun documenting jazz's cutting edge in 1947, when founder Alfred Lion became the first to give Thelonious Monk his own record date. In the 1950s, the label recorded legendary fringe-dweller Herbie Nichols, and purchased the tapes of Cecil Taylor's first album, Jazz Advance, from the failed Transition label. The company issued much of Taylor's '60s music, which included such groundbreaking albums as Conquistador and Unit Structures. The idiosyncratic pianist / composer Andrew Hill did his best work for Blue Note during the decade, as did tenor saxophonist Sam Rivers. Multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy's most fully-realized album, Out to Lunch, was recorded for Blue Note in 1964. The company also recorded such progressively-inclined musicians as drummer Tony Williams, vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, organist Larry Young, and trombonist Grachan Moncur III.

Ornette's association with the label would last two-and-a-half years, resulting in six albums: two great, one infamous, one nearly great, and two which the critical consensus has long held to be mediocre at best—a collective misjudgment in dire need of revision.

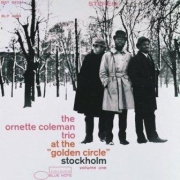

Two excellent full-length albums came out of the Golden Circle gig, The Ornette Coleman Trio at the Golden Circle, Stockholm, Vols. 1 & 2. Ornette led the same trio he'd used at Town Hall in '62, with bassist David Izenson and drummer Charles Moffett. The major change in the group was the evolution of Ornette himself. By 1965, he'd added two new instruments to his arsenal. Cuts like "Faces and Places" and "Dawn" might've been substantially similar in concept and execution to the type of music on his Atlantic albums, but performances such as "Snowflakes and Sunshine"—with Ornette's highly expressionistic violin and trumpet work—and "The Riddle"—with Izenson's trippingly dexterous pizzicato and agile arco bass—were strikingly different. These first two official Coleman recordings following his sabbatical showed Ornette to be as relentlessly inventive as ever.

This is the end of the first part of Chris Kelsey's blog article on Ornette Coleman's Blue Note recordings. For part two, click here.

Tags:

Comments are closed.