The Jazz.com Blog

October 26, 2008 · 6 comments

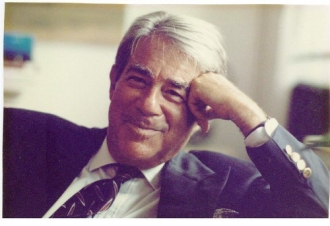

Remembering Peter Levinson

The jazz world is mourning the passing of Peter Levinson, a publicist and biographer and larger-than-life personality on the scene who left us a few days ago at the age of 74. Below Neil Tesser share his reminiscences. T.G.

My friend Peter Levinson died October 21, at the age of 74. In this decade he became known as the author of important biographies, but I’ll always think of him as the last of the old-time jazz publicists. He came from a time when the big bands and the big acts would book two- and three-week stays at the supper clubs that ballasted the jazz circuit: Sinatra or Basie or Woody Herman would employ someone like him to travel with them, showing up in Beantown or Chitown or Vegas or Frisco a couple days before the band to set up the print and radio interviews, and sticking around to plant items with the entertainment columnists that would stoke business throughout the engagement.

I say “someone like him,” but in truth, I haven’t met too many people like Peter. He maintained the trappings of his era even as that era receded, but he never became old-hat—just “old school,” and increasingly admired for that. I couldn’t wait for my first word-processing computer; Peter wrote his press releases and eventually his books in longhand, and employed a secretary to type them up. He expected the magazine writers he contacted, on behalf of his clients, to know something about their beat, to exhibit curiosity about the world, and to practice ethics, because when he started, those people were the rule, rather than the exception; it galled him to watch the disappearance of those virtues as the years wore on.

I don’t think I ever saw him in a professional setting, not even the informal club life of the 80s and 90s, without a jacket and tie—and not just a tie, but something colorful and sharp against a nattily complementary shirt. He had a little of the peacock about him, but that too came from his era, and from the guys he admired most in the business. And he never overdid it; in fact, he seemed a little uncomfortable if caught without that armor when business called. He admired, sought out, and aimed to emulate the elusive quality called Grace—which made it fitting and lovely that when he married for the first and only time, it was to a woman of that name.

From his early work as a press agent he built a universally respected and successful public-relations firm. His clients came to include Dave Brubeck and Stan Getz, Earl Hines and Chick Corea, Peggy Lee and Artie Shaw, Mel Tormé and Kurt Elling. He specialized in jazz, and did so with class. Even as a young writer in my 20s, when I first received pitches from him, I knew that a press release from Peter would be literate and researched, trustworthy and correct; I soon learned that a phone call would be persuasive, insistent—OK, maybe a little pushy—but always respectful. (Hype and taste could co-exist in his world, because for the most part, he represented people he genuinely admired.)

In the 80s, he kept his office in New York but he and Grace moved to the West Coast, and Peter maintained a bi-coastal PR agency. That arrangement soon became unworkable, in large part because the business had changed so much, with artists and labels handling their own publicity (though rarely as well as Peter did for them). So in the late 90s Peter morphed into a biographer, a sometimes underappreciated profession that requires a particular set of skills and attitudes—and a commitment to exhaustive research—to do it right. He conducted scores of interviews, never less than a hundred and usually twice that many, for each of his books, sometimes spending months to track down first-source friends and acquaintances of his subjects. He wrote books on Harry James, then Nelson Riddle, then Tommy Dorsey, and finally on Fred Astaire, the best one yet: Puttin’ On The Ritz, to be published in the spring of ’09. Each of them will remain a valuable research tool, as well as a pretty good read, for years to come.

And each time he finished one of them, he employed the best publicist he knew to make the book a success. The manuscript having received its final proof, he started making calls, later shipping out review copies to the writers overlooked by the publisher, then scheduling readings and lectures and combing his rolodex to set up his own interviews. In the months before he began the next book, I could always count on any conversation with Peter to include him railing against the incompetence rampant in the modern book biz. I would always agree, before reminding him how lucky it was that he could make up for their shortcomings himself.

By then, I’d known him close to two decades. I’d met him in the late 70s, I’d guess: 17 years my senior, he entered my life as a mere business contact, who then became a friend, then more of an older brother; eventually we reached the point of being mutual confidantes and advisers—most fully during the times I stayed at his Malibu home, and most urgently when the canyon fires would make the news in Chicago and I’d call to see if that home had escaped the blazes. (It always did, though sometimes they got close.) I got to know his dogs—he fancied bichon frieses, but one at a time—and his collection of paintings by Haitian artists. I got to spend some time on his huge patio, overlooking a gazebo, staring down at the Pacific, Catalina Island visible on a clear day. And I always shrank back just a little in his home office, the walls groaning under the psychic weight of the photos, dozens of photos featuring Peter with iconic musicians from across jazz and pop history.

A couple years ago, Peter developed something called Progressive Bulbar Palsy. You can look it up on the Web, but I can tell you it’s one of Nature’s nastier pieces of work. It affects a ganglion of nerves that control functions of the mouth and larynx, and it gradually robbed Peter of his impeccable diction and then his ability to speak entirely. Within a year or so, he lost the capacity to fully swallow food, and eventually to swallow at all. The condition itself is pretty rare, but the medical community seems to have come around to the idea that it is in fact a subset, or in many cases a precursor, of ALS—Lou Gehrig’s Disease (or Charles Mingus’s Disease to jazz folks)—and that was in fact the last diagnosis of Peter Levinson. For a man who made both his living and his life with words, I can’t imagine a greater cruelty.

The disease left his mind intact (and until recently, a fair amount of his motor skills as well; he continued to exercise, for instance, and had no trouble walking). For some, that might pose an additional insult, this awareness of one’s own deterioration coupled with the diminishing ability to even discuss what he felt. But for Peter, a man of boundless spirit and a measured but genuine enthusiasm, it merely got in the way. He continued working on his Astaire biography. He cut back on but did not abandon his correspondence. He communicated with a keyboard-operated voice synthesizer, and through his wife and his secretary. He kept going, and so exhibited a personal heroism that I can now add to his legacy: he reacted to tragic circumstances with acceptance but not resignation. We all hope we would handle such a prognosis in such a manner; thankfully, few of us have the need to discover if we were right.

The last time I saw Peter was this past spring. While visiting Los Angeles on business, I had made the familiar drive to Malibu to join Peter and Grace for dinner; but instead of me meeting them at Guido’s, their favorite local restaurant, she’d suggested we eat at the house. When I got there, I understood why. The slurring of speech that I’d first noticed a year earlier had given way to guttural expressions of agreement or consternation, sympathy or humor: the voice synthesizer was on the fritz that night, which led to frustration, but he still communicated to me his questions about my work, my home life, the Chicago scene. He indicated how much weight he’d lost—eating had become so difficult—and managed a shrug and a smile at the idea that this was a helluva way to diet.

I have some strong memories of Peter at his job: tanned and fiftyish, on his patio; at his desk, his hair in relative disarray as he worked the phones; laughing heartily at someone else’s joke; showing simultaneous indulgence and exasperation at one of the dogs. But that small smile of wry acceptance—acceptance but not defeat; Peter Levinson facing his fate with open-eyed pluck—is now the one I think of first.

This blog entry posted by Neil Tesser.

Tags:

I loved reading this blog entry by Neil Tesser. I check in to Jazz.com as much as I can, and this was a reading that went straight to my heart. I felt as if I knew Peter Levinson, as much as you do when you are involved in a good novel. The many friends and acquaintances of Peter Levinson will surely appreciate your insights and memories. Suzanne Cerny

Neil Tesser's rememberance of Peter is simply wonderful. His words capture the true sencse of the man that I knew for the last ten years. It is truly a great loss for all of us. Ric Ross

Wonderful tribute, Neil. Working with Peter on both coasts during the release of "Sunday in New York" I did indeed feel I was catching a glimpse of when showbiz was really showbiz. He taught me alot. Warm Regards (as Peter always signed) to Grace and his family. Libby York

Thanks for a lovely tribute Neil. I got to know Peter as a young writer covering the LA jazz scene in the early 1990s, and he was always looking to make things happen. I started writing for weeklies, and Peter facilitated my first gig with a daily newspaper when he dropped my name to an editor. He also got me a sit-down interview with Artie Shaw, an experience I treasure.

I worked with Peter during the publication of his Tommy Dorsey bio. I worked in the sales department for his publisher at the time, and enjoyed our frequent conversations about jazz. I would sit and listen to his stories about Dorsey and others. A favorite memory of mine was forwarding the fan-mail sent to the publisher's office from WWII veterans who cherished Dorsey and would send letters and copies of photos from their early years, dancing and celebrating the big band era. Best to Peter's survivors. jb

So far I know only the fine Harry James book (the Nelson Riddle - a major subject, therefore a most significant publication - is my next big priority), and I just thought I'd like to say how very much I liked his tone, and the atmosphere, he created when he wrote. It seemed to me to be the most authentic voice, coming direct from the right place: the only place from where such a book should come! (And very unpretentious with it). So I thank him for that - and it saddens me to read here that he had to suffer... Sincerely, RED (Ireland).