The Jazz.com Blog

November 11, 2008 · 3 comments

Charlie Parker in Washington, D.C., 1948

Jazz fans today can hardly appreciate the hostility between the opposed spheres of modern and traditional jazz during the late 1940s. Nothing on the current scene is comparable. Even when the musicians themselves downplayed this post-WWII conflict, critics and fans fueled the fires of contention. It was as if the jazz world of that period wanted to establish its own Cold War, one in which members of the community could swear allegiance to either one camp or the other, but not both. You either subscribed to the progressive ethos of the modernists, or were an old-fashioned advocate of a tradition under attack.

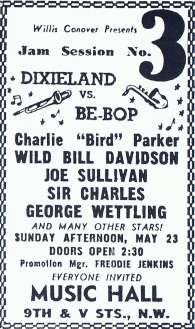

The recent release on compact disk of a live Charlie Parker performance in Washington, D.C. from May 23, 1948 serves as a reminder of this state of affairs. This concert, hosted by Willis Conover, was advertised as a Dixieland vs. Bebop jam session. Two weeks earlier, on May 9, 1948, Conover had presented a similar event, but the choice of Ben Webster to lead the modern contingent at that event suggests the contrast between the old and new was more a matter of marketing than musical values. Webster could not be called a modern jazz player by even the most generous definition of the term.

But when Charlie Bird Parker was booked for the follow-up jam, sparks were sure to fly. For those who demonized the beboppers, Charlie Parker was the head devil. When poet Philip Larkin castigated the unholy trinity of modernism, he included Parker as one of three Ps who had done so much of the supposed damage. (The other two Ps were Pablo Picasso and Ezra Pound.) Pitting Parker and a group of like-minded modernists against Wild Bill Davison and company would definitely put a spotlight on the growing divide between advocates of jazz's future and celebrants of its past.

One can gripe about many aspects of this recording. The sound quality is merely adequate. The piano sounds out of tune (although little known Sam Krupit, then working with Boyd Raeburn, impresses with his smart Tristano-ish solos). Parker is working with an unfamiliar band. Yet the fiery brilliance of Birds solos push all these other concerns to the sidelines.

Parker was at the peak of his abilities in 1948. He was 27 years-old, still in reasonably good health. The previous year he had been released from the Camarillo mental institution in California, where he had received a state-mandated dose of healthy living. In time, his assorted vices would destroy him, and he would be dead in 1955the accumulated damage is perhaps best conveyed by the simple fact that the altoists death certificate estimates his age at between 50 and 60, when in fact Parker was only 34. Such were the ravages Bird inflicted on himself.

But this tragic ending is still some seven years in the future at the time of his Washington D.C. concert, and here Parker is in top form. His lengthy ballad solo on These Foolish Things is full of melodic riches, a relaxed and brilliant performance that ranks among Parkers finer moments, and reminds us of what this artist might have done had he lived into the 1960s, when jazz artists routinely recorded extended improvisations. He is persuasive on two of his most famous compositions: Ornithology and Scrapple from the Apple. But the dramatic highpoint of the evening was Parkers virtuosic assault on KoKo, the bebop workhorse built on the changes to Cherokee.

Here Buddy Rich sets the tempo at a fleet 350 beats per minute. Parker takes off in full flight, and delivers several blistering choruses that assert his supremacy among modern jazz saxophonists of the day. Rich is not a classic bop drummer in the mold of Roach and Clarke and here is playing on a borrowed drum set, yet he locks down the beat and provides a very firm foundation for the rest of the band. It might be the placement of the recording microphone, but to these ears Rich sounds like he is dominating the rhythm section on "Cherokee," pulling everyone else into his conception of the pulse. Despite the passing years and limitations of the audio quality, a listener today can still sense the crowds tense excitement when Rich and Parker trade fours.

Everything after this is anti-climactic. And maybe even the musicians figured it out. A concluding performance of Duke Ellingtons C Jam Blues was cut short when Wild Bill Davison stormed off stage, apparently upset over Parker laughing out loud by the side of the stage. It is an odd story, and one suspects that there is more to the conflict than the details that have come down to us. But even if this final tune had gone on for a hundred more choruses, Bird would still have earned the last laugh. In 1948 he was the king of the jazz world, and others might listen and admireor even disparage if they felt the urge; but no other hornplayer, whether old school or new school, was going to cut him in a jam.

This blog article posted by Ted Gioia.

Tags:

This fine kettle of Mods vs. Moldy Figs reminds me of a vaguely remembered Bop band chart titled something like Blight of the Foo Birds. Parker laughs and Wild Bill gets peckish... These Foolish Things indeed.

Mr. Kurtz reveals that the writer foo-lishly confused two different tunes, Blight of the Fumble Bee and Flight of the Foo Birds. Foo-ey, indeed!

Brilliant. Thanks for this blog! I need to hear this to fully appreciate and know who Charlie Parker really was.