The Jazz.com Blog

November 24, 2008 · 1 comment

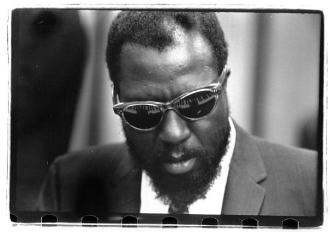

Wynton Marsalis and the JALC Orchestra Play Monk

Chris Kelsey, an editor and writer for jazz.com, recently contributed a two-part article in this space on the Blue Note recordings of Ornette Coleman. Kelsey now turns his attention to the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra's performance of the music of Thelonious Monk last Friday at Frederick P. Rose Hall. T.G.

Marsalis paying tribute to Monk: a cynic (or a Wynton Marsalis detractor; the two types frequently overlap) might roll his eyes at the very idea. And to an extent, that's understandable. One would be hard-pressed to find two jazz musicians who are less alike, and whose individual careers followed more divergent paths. Thelonious Monkthe innovatorstruggled in obscurity until middle-age. For years, his idiosyncratic music was dismissed by the jazz establishment and public as too strange and difficult to be taken seriously. In contrast, Marsalisthe proselytizerachieved fame and fortune early. His music, built upon successful experiments conducted years earlier by acknowledged masters like Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, and Louis Armstrong, found an immediate audience and widespread critical acceptance.

Other considerations: Monk grew up in relative poverty; the Marsalis household was solidly middle-class. Monk was largely self-taught; Marsalis received early instruction from his fatheran estimable jazz pianistand later attended the most prestigious music school in the country. In terms of their art, Monk's represented a dramatic conceptual expansion, whereas Wynton's is largely a reworking of tried-and-true methods. Add the fact that Monk suffered from a debilitating mental illness that eventually caused him to withdraw almost totally into himself at the end of his life, unable or unwilling to engage the world, whereas Marsalis became the personable, popular, and voluble face of jazz to a generation of jazz lovers, and it's easy to see why a skeptic might pre-judge this concert as beyond ironic.

But just as Monk had no choice but to be himself, neither does Marsalis. You wouldn't have hired Thelonious Monk to run an organization like Jazz at Lincoln Center (or even lead it's orchestra), and you don't expect a quantum leap from Wynton Marsalis. The very fact that Wynton shows such deference to his elders makes him an ideal person to headline a tribute like this. Whatever you think of him, no one can legitimately question his love for the greats who made his career possible (most of them, anyway). On a night like tonight, you expect a well-crafted, virtuosic, sincere performance from Wynton Marsalis. He and his band delivered exactly that.

On this occasion, Marsalis and The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra were joined by pianist Marcus Roberts, a professed admirer of Monk, and winner of the first Thelonious Monk International Piano Competition in 1987. Between tunes, actor Courtney Vance read a narration written by historian and Ken Burns collaborator, Geoffrey Ward. The orchestra played a dozen arrangements, most written by current band members. Some of the charts were better than others, but all evinced tremendous skillas well as a healthy (but not excessive) respect for the source materials.

Lead altoist Sherman Irby's arrangement of We See started things nicely. Irby took a fairly conservative approach, using the the melody more or less as Monk intended, not indulging in anything too fancy in terms of orchestration or form (although he did include a terrific sax soli that sounded for all the world like a transcribed Johnny Griffin solo). Roberts took the first solo and impressed immediately. Vance had introduced Roberts as one of the world's greatest living interpreters of Monk's music, which may or may not be true, depending on one's perspective. Certainly, he's a much more conventional pianist than Monk. Here, he incorporated many of Monk's techniques and mannerismsBasie-like repetition, elements of stride, whole-tone runsyet it was apparent that he's not only (or even primarily) about Monk, but rather has the history of jazz piano (pre-Cecil Taylor) under his fingers. There was nothing of Monk's tight-rope-walking spontaneity, nor were there anything even faintly resembling rough edges. In Roberts' hands, gritty becomes elegant, the low-down-est blues nearly rhapsodic. Which is okay. It's not particularly Monk-ish, but it is very appealing.

Wynton followed with a solo that answered the implied musical question, How would Louis Armstrong have sounded if he'd played with Monk? I'm not sure it's a question that needed to be asked. Wynton's solo was attractive in it's way; he played fairly simple ideas, relying on tone and swing to put it over. As always, it was finely-crafted, but there was also that contrived quality which seems to always invade Wynton's playing whenever he's trying to connect the historical dots.

Trombonist Vincent Gardner's ambitious version of Light Blue followed. The title of the piece seems to have inspired Gardner to evoke pastels in his orchestration. This he did by making extensive use of his sax section's doubling skills, writing for flute, clarinet, bass clarinet, andin one tragic instancetwo piccolos. The arrangement featured a great deal of contrary motion, especially between the piano and woodwinds, not all of which was successful, due at least in part to balance problems.

The sparseness of Monk's Evidence makes it a difficult tune to arrange. Marsalis made a valiant effort, though his technique of passing the melodic fragments from one section or group to another (much as he did on his big band arrangement of Coltrane's A Love Supreme several years ago) sounded gimmicky. The tune did serve as an effective showcase for drummer Ali Jackson, however, and trumpeter Marcus Printup played a wonderful solo. Trombonist Chris Crenshaw approached Epistrophy from a reggae angle, which kinda sorta worked, although the rhythm section tended to just lay there, even more than reggae rhythm sections usually do. Alto saxophonist Ted Nash played an impassioned solo on the tune, and Wynton added his relevant two cents. Nash's arrangement of Skippy was one of the evening's more technically demanding moments; his use of woodwind doubles was especially effective, and his solo contained a sprig of Dolphy, which I found refreshing. Trombonist Elliott Mason acquitted himself nicely on the tune, as well.

Other highlights: trumpeter Claude Hendrix's extroverted solo and bari saxophonist Joe Temperley's lyrical spot on saxophonist Walter Blanding's super-tight arrangement of Ba-lue Bolivar Ba-lues-are; a hip Hackensack that featured a Gonsalves-ish solo from tenorist Victor Goines; an exciting Bye-Ya arranged by bassist Carlos Heniquez; and former LCJO leader David Berger's version of Blue Monk, which seemed to grasp Monk-the-composer's improvisatory essence more than any arrangement played all evening.

The best moments came toward concert's end. Wynton's gorgeous arrangement of Ugly Beauty for the saxes and rhythm was an occasion when his Ellington fixation paid big dividends. Lead altoist Irby's huge, vibrating tone conjured Johnny Hodges so effectively, I was almost afraid to look up, for fear I might see Rabbit's ghost hovering in the rafters. Roberts shone, as well. His solo eschewed Monk-ish understatement, instead comprising boppish profundities and lush, Red Garland-like chords. The entire performance was breathtaking.

The final tune, Four in One, features one of Monk's more convoluted melodies, and the arrangement (presumably by Marsalis) embraced those intricacies and expounded them. The piece began with a stab at '20s-style polyphony before kicking into a fast four-four swing. If you know the tune, you know it's tough enough to play at Monk's tempo, and this was much quicker. The orchestra's incredible virtuosity was put to good use. It executed every twist and turn immaculately, with style and excitement. Marsalis's solo burned. He double-timed an already quick tempo with fire, passion, and not a little distinction. There are times when Wynton sounds pedantic on his horn (sometimes it seems like a point of honor that he invoke Armstrong in any and every context), but not here, not now. Tenor saxophonist Walter Blanding added a chop-busting solo, but Wynton's spot is what remains in my ear.

Within the insular confines of the jazz world, Wynton Marsalis has inspired a lot of controversy: because of things he said (mostly) a long time ago; because his success has made him an easy target; because he looks backward for inspiration. Many despair at his apparent unwillingness to include more contemporary jazz styles in JALC's programming. Points taken. But if you can suspend preconceptions and opinions, and just listen to his music, more often than not you're bound to hear something quite beautiful. Not paradigm-shifting, or innovative, necessarily, but beautiful. That's something I figured out only recently. Indeed, maybe I only really learned it tonight. Wynton ain't Monk. But he is Wynton, and that's enough.

This blog entry posted by Chris Kelsey.

Tags:

An extensive article, you wrote, and it offers great honor to Wynton. I wish only for a bit of an excerpt or link to the music.