The Jazz.com Blog

February 25, 2008 · 4 comments

Where Did Our Revolution Go? Free Jazz Turns Fifty

PART ONE (OF THREE PARTS)

The highlight of the Portland Jazz Festival, which concluded its ten days of music-making on Sunday, was a concert celebrating Ornette Coleman's fifty years of making recordings.

A half-century of Free Jazz? It's hard to believe, but Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry's visit to the studio on February 10, 1958 (for the first of the three sessions that produced the Something Else! LP) is now a distant historical event.

This anniversary offers us a good opportunity to look back and consider the impact of Free Jazz (as the work of Ornette and others of his persuasion soon came to be called) over the long haul. Did this music fulfill its promise? Was it little more than cacophony and bluster, as many of its critics asserted at the time? Or, as its advocates claimed, was it a great liberating force, dislodging constraints that had previously held musicians (and indeed large parts of modern society) in check? Did it start a musical revolution? Or was it just one more turn on the revolving door of changing fads and styles? In short, where does Free Jazz stand at the venerable age of fifty?

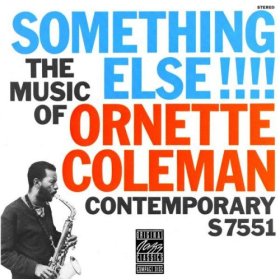

I have mentioned that Ornette's first LP was called Something Else! In truth, most people call it that even today. But the a quick look at the album cover shows that the real name, as broadcast in a huge type font—larger even than the photo of Coleman squeezed into the corner of the layout—was SOMETHING ELSE!!!!

Four exclamation points for Ornette

Few things in life deserve four exclamation points. But the folks at Contemporary Records knew what they were doing in this instance. This was not just another jazz record. Coleman was trouncing on the basic rules of the art form. He wasn't using the same old bop and swing licks every other saxophonist was delivering. Even when his supporting cast tried to prod him with standard chord changes (as pianist Walter Norris and bassist Don Payne repeatedly attempted to do during these sessions), he mostly ignored them. As Joseph Campbell would say, Ornette was following his bliss. And laboring over the harmonic implications of "Out of Nowhere" or "I Got Rhythm" was not blissful enough for this free spirit of Free Jazz.

Norris told me in a 1990 interview: "We rehearsed two or three times a week for about six months leading up to the recording. A number of times we rehearsed at my house. I would take a paper and pen and make notes about the compositions and about what we were supposed to be doing. But the funny thing was that at every rehearsal Ornette would change what we had done the last time. He would change the structure of the song or where the rubato was. And then when we finally showed up for the record date, he changed everything again."

But if Something Else! was a break with jazz traditions and standard practices, what came later would make it seem quaint and old-fashioned by comparison. In follow-up recordings, Ornette moved farther and farther away from the conventional harmonic underpinnings that Norris had offered. Before long, any piano in the band seemed like an imposition to Coleman, an unwanted constraint on his liberated sense of melodic development.

Around the time he was making this first LP, Coleman was developing musical partnerships with other like-minded souls, most visibly with trumpeter Don Cherry (his front line collaborator on Something Else!). Yet perhaps even more important was the arrival of bassist Charlie Haden, who would soon become a regular fixture on Ornette's studio and live bands. The impact of Haden's addition to the group can hardly be over-estimated, and still has not (in my opinion) been sufficiently appreciated by most commentators. I can't imagine another bassist on the planet in the late 1950s and early 1960s, who could have done a better job of adapting to the demands of Coleman's music, and realizing its inner potential. Haden could play loose and free when he needed to, or tighten up when necessary. His time and tone control were impeccable, but Haden knew that these skills were not enough to bring this music to life. He realized that he had to invent a whole new way of playing bass in order to cope with the demands of the new wave. And his inventiveness in navigating through these difficult waters is little short of astonishing. Listen to a song like "Lonely Woman," where he takes a Coleman offering that was little more than a melody, and with very ingenious basswork helps transform it into a fully formed composition.

Yet, increasingly, Coleman didn't want his work to sound like a cohesive composition. The very structure of most jazz performances—based on the idea of an opening and closing melody statement encapsulating individual improvisations—was now open to question. In response, Coleman's 1960 session, Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation features two quartets—one coming out of the left channel of your stereo, another unit assaulting from the right—which maintain a largely unstructured improvisation for almost forty minutes. The composed material now represents only the smallest part of this music, which celebrated content over form, energy over structure. The blueprint for many later celebrated large scale avant garde works—from John Coltrane's Ascension to Peter Brotzmann's Machine Gun—can be traced back to this seminal session.

But if Coleman felt that freedom in music was best achieved without a piano, Cecil Taylor was showing (in his body of work from the same period) that the keyboard could also be a radical tool of musical iconoclasm. Taylor cannot claim to be the first jazz pianist to embrace atonality—a remarkable 1953 track from Lennie Tristano, called "Descent Into the Maelstrom" holds that honor. But Tristano did not release this ear-searing music at the time (perhaps fearful of what the critics, who never treated him gently, might say). When Taylor emerged on to the scene a few years later, he was the trailblazer who pushed the music to the next level.

Taylor also started with conventional jazz song forms, but he was even more acerbic than Coleman in undermining their original meaning. Coleman could play a song such as Gershwin's "Embraceable You" and remind his listeners of the emotional intent of the original tune. His version might be dramatically different from Charlie Parker's or Billie Holiday's, but it still possessed the sweet melancholy of a love song. Taylor, in contrast, purged all of the sentimental trappings from his music. When he played "Lazy Afternoon," it was no longer quite so lazy, more like frenetic afternoon with a thunderstorm about to strike. His "Sweet and Lovely" could more accurately been called "Sharp and Prickly."

As a result, Taylor hardly entered the recording studio during the early 1960s—at a time when Ornette Coleman was recording regularly and other major jazz players, even stars like John Coltrane and Charles Mingus, were paying close attention to the Free Jazz movement. And when Taylor was given the opportunity to record for the prestigious Blue Note label in May 1966, he showed that the backlash against his extreme vision of jazz had only motivated him to go further outside the norms of traditional jazz. On the long opening track "Steps," Taylor undermines every aspect of the jazz tradition. Instead of solos, in which the band supports a featured instrumentalist, each player waiting in turn to step to the forefront, the musicians here seem to delight in slamming their sound into each other's faces. This is the sonic equivalent to J.G. Ballard's novel Crash, which would show up a few years later, a fetishization of collision and impact. At many junctures in this music, it sounds as though piano, drums and horn are all soloing at once — and aggressively so.

But even more striking is this band's unwillingness to settle for long into any one groove or rhythm. If there was one aspect of jazz that was sacrosanct, the holy of holies that (one might think) would never be discarded, it would have been the sense of swing, the momentum that held a jazz song together and moved it forward. From Buddy Bolden to bop, the beat had always been built on hip, repeated patterns, supporting large doses of syncopation in symmetrical and metrical time. Yet Taylor throws this aside in favor of an unsettling, stop-and-start motion that restlessly moves from texture to texture. If you jump around to various points on this ten minute track, you might be persuaded that you were listening to several different songs, so diverse is the basic aural nature of the components. Certainly the performance was well named. For these "Steps" are like the physical ones on a staircase, only taking you away from your starting point. And if ever a jazz composition delighted in moving farther and farther out on a spiraling staircase, this was the one.

Although Taylor's ensemble did its best to keep up with Taylor, this pianist needed no accompaniment to make his revolution. On the final track of Unit Structures, "Tales (8 Whisps)," Taylor's keyboard work dominates the soundspace, and his sheer forcefulness and virtuosity impart a sense of high drama to the proceedings. This pianistic approach to Free Jazz would come to the fore in later recordings such as Silent Tongues, Fly! Fly! Fly! Fly! Fly! and Air Above Mountains (Buildings Within), which remain good starting points for jazz fans who want to come to grips with this radical force in the music's history.

The general public was mostly oblivious to this music. But Free Jazz found a small devoted group of listeners, exhilarated by precisely those elements that turned off most listeners— the outré sensibility, the defiance of convention, the in-your-face aggressiveness of the music. To some degree, the Free Jazz audience was closer in spirit to the followers of acid rock or avant garde classical music, than to the fans who enjoyed other Blue Note releases. Unit Structures and Free Jazz were unlikely to appeal to hard boppers who wanted to snap their fingers and swing to the groove. It was little wonder, then, that the Blue Note connection did not prove sufficient to establish Taylor's commercial viability. After Conquistador, a strong follow-up LP which in some ways compares favorably to Unit Structures, Taylor recorded no more for Blue Note. Over the next decade, he would increasingly bring his act overseas, where avant garde currents of all sorts found a more hospitable home.

END OF PART ONE

For part two of this essay, click here.

This blog entry posted by Ted Gioia

Tags:

I'm a devoted listener who was born in the fall of 1957. Around the age of one or two, as soon I learned to how to manipulate the tuning dial on a radio, I often tuned into what I thought to be the greatest music on our planet. This always angered my parents, who'd consistently yell at me to, "turn that NOISE off!". Squares, they were.

Free Jazz lives! There should alaways be a space for atrists who have a different perspective. "Noise is an essential part of of the universe of music and sound. I once spoke to the late great saxophonist Sonny Stitt and he told me "noise can be music too." Moreover, one persons music is anothers noise and vice a versa.

Please see additional info at jazzhouse.org within the reprinted College Music Symposium article: Misconceptions in Linking Free Jazz with the Civil Rights Movement.

Free Jazz continues to amaze!I am a musician myself, and ever since I picked up an instrument I felt most comfortable in a situation with others that relished experimentation! improvisation is not burdened with classification, and where the possibilities are endless. It was great to learn about the origins of free jazz, but what makes it so special is that most of the artist are not famous (mostly because they performed the music the way wanted to) anyway, some of my influences are Sun Ra,Wayne Krantz, Ornette Coleman, and the late but great Jaco Pastorius..he did everything his own way, utilizing all his musical ideas and putting them to good use.