The Jazz.com Blog

May 12, 2008 · 1 comment

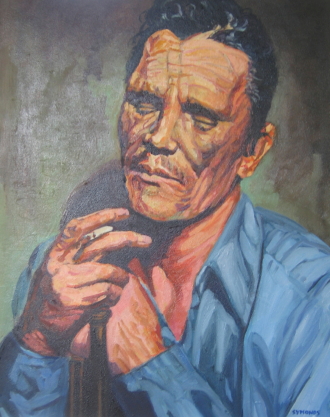

Could Chet Baker Play Jazz? (Part One)

This week marks the 20th anniversary of Chet Baker's death after his apparent fall from a second story hotel window in Amsterdam. Baker was 58 years old at the time of his passing.

For more than a year leading up to this event, I had been trying to arrange a face-to-face interview with Baker. I was in the midst of researching my book on West Coast jazz, and gradually tracking down the surviving musicians who had dominated the California scene in the 1950s. I especially wanted to talk to Baker, who was one of the reasons I was writing the book.

Many of the West Coasters had been dissed by the critics, and I hoped to set the record straight. Baker, more than most, had been subjected to an unfair degree of ridicule and caustic dismissals. Even after his death, these attacks continued. Here, for instance, is a typical put-down from 2002, published by a movie critic masquerading as a jazz expert in the pages of The New Republic: "Baker, in my view, could not play jazz, and did not play it. He did torch songs on dead batteries."

This same author's "humorous" take on Baker's fatal fall was: "We are talking about Chet Baker, after all . . . he had been dead for years already."

This is fairly typical of the 'state' of Baker criticism in certain fashionable circles.

Of course, the recordings tell a different tale. A live concert from Tokyo preserved on film and tape a few months before Baker's death shows him playing at top form. Baker had left the hard stuff at home in response to stringent Japanese drug enforcement policies � Paul McCartney had been arrested at Narita Airport for marijuana possession a few years before, and musicians finally figured out that Tokyo was not Amsterdam. As a result, Baker stuck with methadone during this visit, and played with a fire and creativity that put the lie to those who considered him a washed-up junkie who could no longer handle the horn.

Yet Baker's soloing, even on a bad day, served as testimony to his exceptional knack for constructing melodic phrases. More than almost any soloist of his generation, Baker played what he heard in his head. He didn't have Berklee licks to fall back on—just what his ear told him. And what an amazing ear. Here is a revealing story, as told to me by Larry Bunker:

"If you put chord changes in front of [Chet], it didn't mean anything to him. He would say in a self-deprecating way, 'Well I don't know the chord changes to the song.' . . . We would go and sit in with bands, often playing until five in the morning, and any of the songs they would play, Chet knew. But he would ask a question that would puzzle the other players. 'What's my starting note?' he'd ask. They thought he was putting them on or something, but all he wanted was the first note on the trumpet so he would know where to start the piece. From there he could navigate any song by ear. Sometimes the other players would try to fool him. They might try to trick him by playing 'All the Things You Are' in E or 'Body and Soul' in B rather than D flat. But Chet would have no problems with doing that. It was the other musicians who ended up struggling—they had tried to give Chet problems, but they just caught up themselves."

Grover Sales told me a similar story. Baker had been enlisted to accompany the Brazilian singer-songwriter João Donato for an engagement at the Trident in Sausalito. Chet would show up late for the gig, with little preparation . . . and Donato would rip through these fast, intricate original compositions, with all sorts of clever chord changes and modulations. Baker would fly over these pieces like he had been playing them for years. He didn't need to see the charts—they wouldn't have meant much to him anyway. As soon as he heard the music, he could work his magic.

Here was the letter I wrote to The New Republic in response to their public flogging of Baker's musicianship—a letter never published by the magazine. I should add that sending letters of this sort is not standard practice for me—I haven't sent any in the six years since I wrote this one. But I felt compelled to jump in on this issue.

Dear Editor,

I am dismayed that The New Republic provided David Thomson with a respectable forum for advocating his ludicrous position that Chet Baker "could not play jazz."

When I conducted my research on Baker for my book on West Coast jazz, I encountered numerous musicians who were lavish in their praise of Chet's improvising skills. They told me many tales of Baker's tremendous prowess in performances and jam sessions.

When I accompanied trumpeter Art Farmer during a master class at Stanford, he held up Chet Baker as a role model to the students, calling particular attention to the brilliance of his improvisations. Recently Keith Jarrett -- an artist who does not give out praise lightly -- has also commended Baker's rare talents.

But, then again, I did not need these testimonials to verify the matter. Like Thomson, I too heard Baker perform in the San Francisco area during the 1980s. But contrary to what one might gather from Thomson's review, Baker played at a very remarkable level every time I heard him.

Thomson reminds me of those Cold War critics of West Coast jazz, who claimed that the popularity of Chet Baker and his contemporaries was simply the result of aggressive marketing by the record companies. Well, the marketing campaigns stopped decades ago, and Baker's recordings still sell in large quantities. Indeed, Baker probably has more releases available today than at any point in his lifetime.

Look at the record. A half century has passed since Chet Baker first hit the scene -- selected by Charlie Parker from among the dozens of top notch trumpeters who hoped to get into Bird's band (not a bad recommendation for Baker there, huh?). Most of the other recordings from that era have disappeared from the bins, forgotten long ago, yet Baker's music has only grown in popularity and influence.

One can only conclude that those who are waiting for the "hype" to die down, and for Baker's undeserved popularity to wane, like one more passing fad from the 1950s . . . well, they better dig in for the long haul, because they will be waiting for a long, long time.

Ted Gioia

Nope, they never published that one. It stayed in the dead letter office until today.

Art Farmer's praise of Chet is particularly worth noting. The conventional wisdom is that Farmer resented Chet, and thought he was a faker who couldn't play a horn. Yet I heard Farmer—unprompted—tell a group of students that they needed to listen to Baker if they wanted to hear how a masterful musician could construct a compelling solo without resorting to flashy high notes or pyrotechnics. So much for the conventional wisdom. . . .

Put simply, Baker was one of the greatest melodic soloists of mid-century American music. And—despite what you may have heard elsewhere—he was one of the most original stylists of his generation. Chet is one of those trumpeters who is easily identified in a blindfold test after only a few notes. Yet he has more than occasionally been dismissed by those who should have known better as some watered-down imitator of Miles Davis. True, both artists played "My Funny Valentine" (although Chet recorded the song years before Davis). True, both musicians developed a "cool" style. But their approach to phrasing, intonation, structuring a solo were markedly different. Even a single, held note—which Chet would typically play cleanly and Miles would characteristically bend -- would tell you which of the two you were hearing.

You should listen to every recording without preconceived notions of how it will sound. The received opinions are often wrong, but even when they are right, listeners need to bring their own emotional compass to the game. Baker, in particular, will distract you from the essence of his artistry if you pay too much attention to the particulars of his biography. Given the self-inflicted damage of his lifestyle, he had no right to sound as good as he did. He was, as the cliché goes, his own worst enemy. But somehow, the music managed to shine through, even as the musician showed increasing wear and tear.

This is part one of Ted Gioia's essay on the music of trumpeter Chet Baker. For part two, click here.

Tags:

I totally agree with the assertion that not only was Chet an improviser, he was one who was held up by his peers as a singular talent. As a lifelong jazz trumpet player myself based in the Buffalo NY area, I can speak with some amount of authority when I say that the level of creativity in Chet's playing is staggering. I wish it would have been possible for Chet to enjoy at least a part of his middle and later years away from drugs, as it obviously had a negative effect on his playing in a number of ways. It's a testament to his constitution that he could have as long of a career as he had, given the health issues he dealt with for 30 years.