The Jazz.com Blog

May 13, 2008 · 3 comments

Chet's Children: The Legacy of a Fallen Jazz Star

Today is the twentieth anniversary of Chet Baker's death from an apparent fall from his second story hotel window in Amsterdam. Below is the second part of Ted Gioia's look back at the career of this talented and controversial artist. For part one of this essay, click here.

I had seen Baker perform on a number of occasions, but I never spoke to him until a gig at Kimball's in San Francisco about a year before his death. This was around the time of his exceptional live recording in Tokyo, and he showed up on the West Coast playing at top form.

Like many in the jazz world, I always half expected Baker to lay an egg on stage. We all heard the stories of his out-of-control lifestyle, his arrests and incarcerations, his drug use. We knew he had lost his teeth in a beating. He was a guy who didn't give a damn—just look at how he lived in his life. Why should he care what the fans thought about his playing? Why should he give it his all on stage? Yet every time I saw Chet play in person, he was totally in the moment.

I tend to think that the good Chet and bad Chet came from this same place. Baker's obsession with immediate sensations and instant gratification, his fixation with the here-and-now, are what made him a great improviser . . . and also an easy prey for drug dealers, as well as a victim of his own worst inclinations. He lived in the present instant. He didn't worry about tomorrow. He didn't worry about yesterday. He exhibited a type of personality structure perfectly suited for the spontaneity of jazz . . . and for a tragic, fragmented life.

I spoke to Chet during a break at his Kimball's gig. I told him about my research into West Coast jazz. I showed him some of my writings on jazz. I hadn't published any books at that point, but I had some photocopies of articles which I thrust into his hands. I asked whether I could interview him during his San Francisco visit. He agreed, and told me to give him a phone call at his motel the following morning.

Once again, the stereotyped view of Chet would suggest that his mind had been burnt out on drugs, that asking him about events in the 1940s and 1950s would be a pointless and futile exercise. Yet even before I approach Chet, I had talked to people who knew him, and they reassured me on this count. Baker was a shrewd and smart guy, and I would find that he had plenty of interesting things to say—if (and this was the invariable caveat) he decided to do so. In my conversation at Kimball's, I got the same impression. If you could get past the surface con job—and Baker was almost as good at conning you as he was playing the horn—he had a sharp and savage way of thinking, and knew the score better than anyone.

The next morning I phoned Baker at his motel. No answer. I phoned again and again. Still no answer. I decided to make the forty minute drive from my apartment on the Peninsula, and show up at the trumpeter's motel room door. Baker had set up shop at a seedy Travelodge in a bad part of town. At first, I was a little surprised—didn't visiting jazz stars stay at nicer places than this? But Chet probably picked this place for reasons that had little to do with French milled soap and turndown service. He wouldn't answer the door for me, and the guy at the front desk told me that Mr. Baker had refused to let the maid come in to clean his room.

I slipped a note under Baker's door, urging him to contact me. And he did . . . about four weeks later.

I was sharing an apartment with a former college classmate, trying to cut down on the cost of rent to support my expensive habit - going to jazz clubs and buying CDs. I came home one evening to see a note on the kitchen table. It simply read: "Chet Baker phoned." When my roommate showed up later, I asked him whether he had written down a phone number for Mr. Baker. "No, I didn't get one." Needless to say, he was not a jazz fan (my room-mate was an aficionado of the Sex Pistols), and wouldn't know Chet Baker from Mary Baker Eddy. The trumpeter, for his part, never phoned again.

I had one last shot at getting an interview. Kimball's announced a return engagement for the Chet Baker Quartet, and I showed up on opening night, determined to secure the trumpeter's cooperation for my book and research. But when I arrived at the door, the sign read: "Playing Tonight: Les McCann." I asked the ticket seller; "What happened to Chet Baker?" The response: "He was ill and had to cancel. I think he might be in Europe."

I knew, in that moment, that I would never have my conversation with Chet Baker. When I read about his death from a fall a few weeks later, I was not surprised in the least. Somehow I had been expecting it. Baker had been courting disaster for years. Finally it had caught up with him.

Twenty years have now elapsed. What can we say about Chet now, with the benefit of perspective and hindsight? Where does he stand in the jazz pantheon?

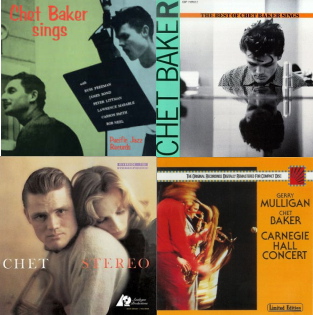

First, Baker's music is probably more popular now than during his lifetime. The first time I saw Chet in person, at a small club in the San Jose area, there were fewer than twenty people in attendance. This morning, I checked on Amazon.com, and found that the on-line retailer lists more than 500 Chet Baker releases on its site. Yes, there is a glut of Baker's music available for sale—the result, to some degree, of his haphazard approach to his own discography. But the sheer numbers also reflect the marketplace, the underlying demand for his music. These CDs wouldn't be out there if Chet didn't have a devoted fan base. Despite everything Baker did to saturate the market, his audience always wanted -- and today still wants -- more.

But even more striking—and surprising—is the influence Baker has exerted over later trumpeters. This is especially true in Europe. In fact, one could make a case that no trumpeter of the last fifty years has had more influence among European jazz players than Chet Baker. Check out the ECM releases of artists such as Tomasz Stanko, Enrico Rava or Nils Petter Molvaer, and you can hear how they share Baker's aesthetic values, his preference for melodic phrasing over flashy licks and practice room patterns. Or listen to Till Brönner or Paolo Fresu or any other of a host of other outstanding European musicians. Baker, the man who couldn't play jazz (according to his critics), is a key role model.

A great role model, too, in my opinion. If you wanted to teach young jazz players how to hear, how to play with their hearts and their ears, rather than just with their fingers and method books, Baker would be the place to send them. His range may have been limited, his technique less than virtuosic, his work ethic suspect . . . but the key to improvisation is, put simply, the ability to construct fresh and interesting phrases in real time, to build new melodies in the place of the old ones. And in this, Mr. Baker was nonpareil.

How ironic, though. Baker achieved greatness in many areas, but "role model" and "mentor" would not be the first two words he would have used to describe himself.

You wouldn't want to send your son or daughter on the road with him. You wouldn't want him to take over the advice column from Dear Abby or Miss Manners. Yet, is it possible that Baker stands, twenty years after his death, as a figure others should . . . emulate?

What a peculiar turn of events! I suspect that this troubled artist gravitated to Europe because of the easy money and fairly lax attitudes toward drugs. He performed and recorded widely—perhaps even excessively— to support a habit that had come to dominate him. But the end result was he exposed millions of Europeans, including many up-and-coming musicians of great stature, to his artistry.

They are now Chet's children. And, strange to say, he has finally, oddly, incongruously . . . proven to be a pretty good dad.

This blog entry posted by Ted Gioia.

Tags:

I was Chet's longtime closest friend, personal favorite drummer and confidant. Check out my website (arttfrank.com) and you'll see a quote from Chet about me, and be able to hear two sound samples of us playing together. Irecently finished my book of memoirs about Chet, and it should be published sometime soon, plus a major movie will be written from the book. Also, check out the Chet Baker Foundation website founded by his son Paul a year and a half ago. (chetbakerfoundation.org) and check out the great luminaries I contacted to add their names to the list of Honorary Directors, and Honorary Board Members. Each one is a personal friend of mine. Thnaks for writing what you did about Chet. I appreciate it. Where are you from? Stay in touch, Artt Frank.

hey uncle artt how are you doin ? i miss you and love you so very much you are the best . i just want you to know that im going to do my best and do well ! thats a promise and it definettly will not get broken . you always told me that if you worked hard enough for what you want you will get it ! and you have proved that to me i love you and respect you so much for that and always will your the BEST !!!!! i love you uncle artt :) JOSHUA.H.LINLEY

CAn you tell me more about the chet baker foundation? I meet Bruce Guthrie at a non-profit semimar and he provided a card with website address of chetbakerfoundation.org,no phone contact numbers were provided. Thank you, Gina Carroll