The Jazz.com Blog

June 16, 2008 · 1 comment

A New Technology to Bring Old Jazz Recordings Back to Life

Over the years, experts have struggled to take old recordings and make them sound like new. But none have been as ambitious as the folks at Zenph Studios, a high tech start-up in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Zenph does not try to clean up the sound of the old records. They bypass the recordings completely, and try to recreate the sound of the original instruments that made the music. Their work so far has focused on piano, but I have heard an unreleased recording of their recreation of a jazz bass in essence, an attempt to present Ray Brown on the bass . . . but without Mr. Brown or even a bass. The sound is entirely software driven.

John Walker of Zenph tells me that the bass recording I heard wasnt ready for release yet it is only 94% ready, in his opinion. (My full interview with Walker will be published in this space later this week.) But my ears couldnt detect the missing 6%. I would challenge any jazz fan to pinpoint the ways in which this software-driven sound falls short of the real Ray Brown. We have notes, bends, finger clicks, strings slapping against the wood, dynamic shifts, and above all the distinctive sound that was this artists trademark.

Whoa, this is like the old "Ella or Memorex" dilemma to the order of ten.

("Golly gee, Mr. Science, are you saying we can enjoy a jazz band recorded without any humans? Have you checked with the musicians' union on that one, Mr. Science?")

Through their partnership with Sony, Zenph released their debut project last year, a recreation of Glenn Goulds 1955 recording of The Goldberg Variations. I know the original very well, and (like many fans) distinctly prefer it to Goulds 1981 version, made shortly before the pianists death, despite the stereo sound and digital recording quality of the latter. The only disadvantage of the 1955 version is the (comparatively) poor sonics. But Zenphs reworking, using Yamaha's Disklavier Pro technology as an interface, is both true to the original, and absolutely up-to-date in its audio quality.

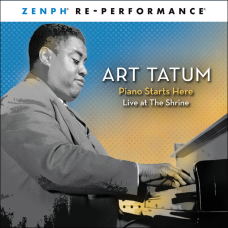

You can imagine my excitement when I learned that Zenphs follow-up project aimed to do the same for Art Tatums 1949 live recording at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. I have cherished this performance ever since I first heard it on LP back when I was in high school. I know this recording intimately. In my opinion, it presents Tatum at his absolute peak. The artist was clearly inspired by the rare opportunity to move out of the smoky, noisy nightclubs where he typically worked and present his music in front of a large audience at a real concert hall.

The sound quality on the original Tatum recording is, alas, abysmal. Even by the low standards of 1949, the audio is disappointing. Back when I first heard this recording I was probably sixteen years old at the time the murky sound bothered me. But over the years, I have listened to so many old recordings, many far worse in their audio distortions, and hardly even think about these matters any more. I have come to accept the limitations of pre-high-fidelity recordings, and try to get beyond the surface noise and flat, cloudy ambiance and into the music itself.

Even so, the chance to hear what Zenph had done with this famous concert got me quite excited. And the Zenph Tatum CD (released earlier this month) did not disappoint. Indeed, I was stunned and deeply moved. It was as if I had been listening to this Art Tatum recording for years from afar, two rooms away, with walls between me and the piano, and then all of a sudden -- I was invited into the concert hall where the performance was underway. (In fact, the Zenph recreation was recorded before a live audience at the Shrine Auditorium, in an attempt to match the original concert in every particular.)

For all his rapid-fire virtuosity, Tatum was an artist whose greatness cannot be reduced to sheer speed and dexterity. Yes, its true, this artist was much more than just finger-busting scales and arpeggios. The music-inside-the-music is what sets him apart: the chord constructions and passing harmonies, the intricacies of his left- and right-hand interaction, his tone control, his dynamics. These come through on the Zenph CD with a vividness that cannot be matched by any original Tatum recording. Even an old Tatum fan like me, who thought he knew everything that this Shrine concert had to tell me about the pianist, heard things I had never noticed before.

Some have already objected to this technology. Marc Myers admits to "mixed feelings" about the recording, and tosses out the term Bizarro Tatum. He conjures up images of Dolly the Sheep, suggesting that this is more clone than original. Another blogger argues that this CD "lacks soul" and "in-the-moment" creativity. I suspect that many other jazz purists (and we all know how finicky they are!) will express similar views.

But is this purist attitude a fair one? After all (as Walker points out in our forthcoming interview), the original recording of Tatum at the Shrine was made at the wrong speed, dramatically distorting the music. Who can claim that this old technology with its misrepresentation of Tatum's performance is more authentic than Zenphs high tech effort to recreate the original sounds that the pianist played? Remember, no recording is an original every CD is an intermediary between the listener and the performer. The real test of any recording technology is how closely it matches the performance. From that perspective, Zenph is light years ahead of the folks who made the Shrine Auditorium recording back in April of 1949.

Despite these advantages, there is a certain risk that this technology will meet the same fate as colorized black & white motion pictures. But I think that analogy is not an appropriate one. The colorized films distorted what the artists originally intended. The Zenph recreations, in contrast, are (to my ears) absolutely faithful to the music as it was originally performed.

And I cant help pointing out the similarity between the issues at stake here with those relating to non-human intelligence and the parameters of the so-called Turing test. Alan Turing suggested that our objections to a technologys authenticity become meaningless if educated observers cannot identify specific ways in which the constructed reality falls short of the original. To my mind, the Zenph recordings pass the Turing Test. Given this, I would suggest that objections to it fall into the realm of fuzzy metaphysics.

And I will take a good jazz recording over fuzzy metaphysics any day of the week.

But the future implications are rich with philosophical implications. What happens when this technology can handle entire jazz bands, with all of the major instruments replicated? What if the audio technology is married to artificial intelligence? Could we have software that creates brand new solos indistinguishable from historic ones by Bird or Prez? Could we put together different jazz musicians from different eras, and watch them work their magic? Would you like to hear a cutting contest between Louis Armstrong, circa 1930, with a 1945 Dizzy Gillespie and toss in Brownie, Wynton and Miles for good measure?

Click here for my interview with John Walker, President and founder of Zenph. Also, New York-based fans can hear the Tatum performance live at the Apollo Theater on June 22 in a benefit concert for the National Jazz Museum in Harlem.

This blog entry posted by Ted Gioia.

Tags:

What the hell is wrong with you people? Does anyone actually think that this sounds like Art Tatum? This sounds like a piano roll and not a very good one at that. A computer can not recreate the humanity and energy of any performance. Maybe the excitement about such a product explains the new generation of mechanical pianists, (those with beating hearts but no soul) Throw this garbage away!!!