The Jazz.com Blog

July 17, 2008 · 0 comments

Sonny Rollins & Charles Lloyd in Italy

Every summer, jazz stars descend on Perugia, Italy for the Umbria Jazz Festival, now in its 35th year. Ted Panken sends in his third update, below, covering exciting performances by Sonny Rollins and Charles Lloyd. (Click here for Pankens first and second reports from the festival.) Check back soon for his final dispatch from Italy.T.G.

Jazz obsessives often indulge in a form of fantasy baseball about the movers and shakers of the music they love: Wouldnt it be great if so-and-so played with so-and-so instead of such-and-such for this-or-that event?

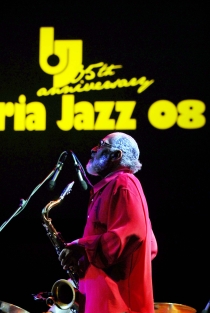

Such thoughts came to mind at the Umbria Jazz Festival on Sunday night, when Sonny Rollins brought his groupClifton Anderson, trombone; Bobby Broom, guitar; Bob Cranshaw, bass; Kobe Watkins, drumset; Kimati Dinizulu, hand drumsto the Santa Giuliani Arena to play the Umbria Jazz Festival. Perhaps 5,000 souls paid 80 Euros a ticket to hear the 78-year-old legend fulfill the operative trope of his singular careerto execute the impossible by shaping cogent, poetic musical architecture on the tenor saxophone while navigating the high wire of tabula rasa improvisation.

Already in town since the previous Thursday, Rollins, a striking figure with his white beard, flowing red shirt and white pants, was rested and ready for feats of derring-do. This was apparent on the set-opener, Heres To The People, on which, over a powerful Afro-Funk groove, Rollins swung the vamp for five minutes or so, probing the contours of the line, facing Broom to set up a motif here, facing Watkins to develop another there, walking one end of the stage to the other to get in the flow. At the exact moment that it occurred to the listener that he might worry the vamp all night, Rollins shifted gears, beginning a 20-minute tour de force on which he roared like a lion from the top to the very bottom of the horn, building momentum to a point where it seemed impossible to take it further, but then ratcheting up the flow even more, crossing the right hand over the left to find tones that only he could play, and finally winding down to a collective holler of approbation from the accumulated voices that faced him.

No other living improviser can generate such catharsisintellectual abstraction at the highest level projected with the arena energy of U2 or the Rolling Stones. To sustain such energy for a full concert at 78 is another question, and Rollins retreated to first gear on Noel Cowards Someday Ill Find You, which appeared on the B-side of his iconic Riverside album, The Freedom Suite with bassist Oscar Pettiford and drummer Max Roach. Rollins finds it painful to listen to most of his recordings, but he likes this one, as was evident last October when we played the recording on New Yorks WKCR, where he joined me to publicize a much-anticipated Carnegie Hall concert with Christian McBride and Roy Haynes. Earlier in our three-hour encounter, Rollins had asked that the monitors be turned down while his music was going over the airwaves, but for this he smiled and swayed his shoulders as he and Max Roach threw melodies and rhythms at each other on the final section of the song.

On this evening at Perugia, fifty years after the 1958 recording, Rollins played it straight, caressing the melody of this love song with a heroic, romantic, quasi-operatic tone in the manner of his idol, Coleman Hawkins. Then he signaled for exchanges with drummer Watkins, and fantasy baseball began, as Watkins dissipated the mood, responding to Rollins postulations over the next five minutes or so with the same unrelenting beat and power chops that had fired the previous piece. Hank Jones likes to say that every song has one correct tempo, and this was not it. There was no air, no texture, no space in the flow. Nor did Rollins provide even a sketchy arrangement by which Watkins could orient himself. I was reminded of Jack DeJohnettes remark several years ago that Sonny likes to have the time solid, so that he can juxtapose playing across or under or through it. He is complete; he hears the drums, bass and piano in him, and he plays by himself.

At the time, Rollins himself cosigned that remark: As abstract as I often like to get, I've always liked to contrast abstraction against something steady," he told me. I play a lot of different stuffCaribbean things, straight-ahead, a little backbeatand I need a drummer who has a little bit of range, who isn't locked into one style of playing. A lot of jazz drummers are great at straight-ahead, but if you want to go into something else the feeling is not quite as genuine. I demand that the basic pulse and the chord structure be present throughout; I always have the song in mind regardless of what I do."

Watkins showed his range on the subsequent Rollins calypso, nailing the groove for Rollins powerful but attenuated declamation, which followed lengthy solos by Anderson and Broom. He and Dinizulu put a 70s lounge sound on In A Sentimental Mood, which began with a 7-minute Cranshaw solo, followed by another 6 minutes by Broom and 5 minutes by Anderson, while the feel on They Say That Falling In Love Is Wonderful was a relentless, bassy four-to-the-floor, with no ride cymbal air to give flight to Rollins ebullient variations, which included heart-stopping quotes from the Lester Young lick book placed in the most improbable spots. The crowd spontaneously poured up to the lip of the stage to soak Rollins spirit-raising Dont Stop The Carnival, and compelled an encore, in this case a 40s or 50s pop song with the quality of an Italian aria whose melody Rollins, now rejuvenated, bellowed operatically for ten minutes or so, before tearing into Now Is The Time with singular momentum.

Rollins maintains the equilibrium that he needs to do what he does by creating an environment in which he himself generates his challenge, an approach that generates no small amount of dead space in a two-hour concert. While he cant approach Rollins mastery of sound projection, rhythmic impeccability, and harmonic imagination, Charles Lloyd, recently turned 70, has over the last 15 years surrounded himself with improvisers whose strong tonal personalities will intersect with his own to create a flow based on mutual dialogue, an approach he used to great effect between midnight and 2 a.m. on Sunday at the Morlacchi Theater.

In regard to tone, Lloyd blends the Lester Young-Stan Getz approach (following Prezs example, he blows into the tenor at an angle, from the right side of his mouth) with that of Ben Webster, while in matters of vocabulary he is a descendant of late 50s Rollins and John Coltrane circa 1959 to 1965. Prodding him were pianist Jason Moran, bassist Reuben Rogers, and drummer Eric Harland, an up-to-the-second rhythm section, who kept the rhythms varied and modern, the pulse grounded, and the harmony polytonal and abstract. Lloyd started off tentatively, picked up steam with a Websterish Come Sunday, and played with ever-greater strength as the wee hours encroached. He finished for good at 2 AM, even as the full-house called for more.

Tags:

Comments are closed.