The Jazz.com Blog

July 02, 2008 · 7 comments

Buddy Bolden on the Holodeck

Recent articles on jazz.com have raised troubling questions about new technologies that, not content to merely improve the sound of old recordings, employ the latest advances in computerization to robotically re-create the original performances. (See previous blog articles here and here to get up to speed.) Roused from one of his periodic slumbers by these developments, jazz.com's resident curmudgeon Alan Kurtz falsely concluded that, behind his back, our web site had pulled a switcheroo from jazz to science fiction. Desperate not to be left behind, Alan frantically jumped into the fray. (Has Mr. Kurtz ever seen a fray he hasn't jumped into?)

We suspect that Alan's contribution below is the result of an overheated imagination and a troubled childhood spent with Forrest J. Ackerman as his babysitter. But one never knows, do one? Readers are invited to share their own views by adding their comments or emailing them to editor@jazz.com.

What was it Rod Serling used to say? "Submitted for your approval . . ." T.G.

Hackneyed or not, it was a dark and stormy night. My meeting with the Mad Scientist, as I'd begun to think of him, had been scheduled after hours to accommodate my day job as an actuarial archivist. Arriving 20 minutes late, I nearly drove past the secluded entrance, which under even ideal atmospheric conditions might be described as dimly lit and poorly marked. "Got an appointment?" demanded the security guard at the front gate, his face hidden beneath the hood of a yellow slicker dripping rain from every crease.

"I'm Kurtz," I hollered cheerily from the cozy confines of my sedan. The sentry motioned for me to roll down the window. "Kurtz," I reiterated against the blustery wetness now dampening my countenance but not my enthusiasm. "The jazz writer. I'm here to interview Dr. Cabman."

Without a word, the hulking figure retreated to his roadside shack, where he could just barely be seen to consult a clipboard. Momentarily, the wrought-iron fence separated automatically and he waved me through without again leaving his shelter. I never did see the man's face. For all I know, it could have been the Mad Scientist's latest experiment in reanimation.

Well, okay, that's unfair. Cabman Laboratories is a respected cutting-edge software firm, not Castle Frankenstein. Even so, something about the place gave me the creeps.

I parked as close as possible to the main building and dashed for its lobby. One advantage of after- hours meetings, I'd long ago discovered, is plentiful parking space. Since the regular receptionist had left for the day, I was met instead by a second security guard. This one had a face. After signing me in and inspecting my attach case, he led me through several corridors and up a short staircase to the executive suite, where he transferred custody to a private secretary. With polite efficiency, she offered me a choice of coffee or tea and, once I'd served myself a cup of brisk Earl Grey, seated me on a couch while she left to inform the Director, as she called him, that I was waiting.

Ten minutes later, I was ushered into the Mad Scientist's office, a tastefully furnished but by no means sumptuous setting for an immaculately groomed, secretive man in his mid-30s who, had he ever been photographed, would've probably looked exactly like his picture. Proffering a perfunctory handshake, he motioned me to a chair opposite his desk, behind which he settled with a noncommittal assurance likely calculated to intimidate less seasoned visitors. Naturally that stuff won't work on me.

"Now see here," I got straight to the point. "What's this about reanimating Buddy Bolden?"

Dr. Cabman cleared his throat and affected a look of strained patience. "We prefer the term 'simulate,'" he corrected me.

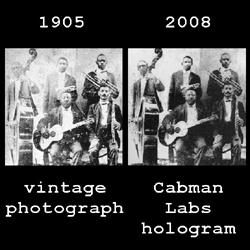

"Fair enough," I conceded. "But what gives?" This was significant. As any schoolchild can tell you (or could if we had a half-decent educational system in this country), Buddy Bolden (1877-1931) was jazz's first truly mythic African-American cornetist, dominating New Orleans proto-jazz from the turn of the century until 1907, when he was certified insane and committed to the Louisiana state asylum at Jackson. Confined there for his remaining 24 years, Bolden died long forgotten and was consigned to a pauper's grave in The Big Easy. He left no known recording, but his loudness was legendary.

"It's true," Dr. Cabman allowed. "After years of basic research and a substantial investment in supercomputers, our team has simulated 'Buddy Bolden's Blues' to a confidence level of 97%, plus or minus 2% to account for transient anomalies."

"'Buddy Bolden's Blues,'" I sought to clarify. "You mean 'Funky Butt,' right?"

Dr. Cabman's strained patience this time expressed itself in a fleetingly perceptible wince. "That is another name for it, yes."

"But how on earth?" I honed in. "Don't tell me you found that long-lost wax cylinder he supposedly once recorded."

"Unnecessary. Historical documentation is not required, nor would it be of much use even if available. Our simulations are entirely software driven."

"You don't say! Can you be more specific?"

"Well, I'm contractually precluded from divulging trade secrets, but speaking broadly, we apply necro- retrograde engineering. In Bolden's case, we minutely analyzed jazz cornet and trumpet styles from King Oliver to Louis Armstrong to Roy Eldridge to Dizzy Gillespie, then mathematically extrapolated preceding styles through regression analysis and recursive algorithms back to Bolden. Voila!"

"So it's different, then, from what Zenph Studios did with Art Tatum."

"Child's play," Dr. Cabman said indulgently, leaving no doubt he meant Zenph, not Tatum. "Putting a high-tech player piano in the middle of a stage, no matter how dramatically lit, is like inviting audiences to look at a motion picture projector set up at the front of a theater, with no film. People want a show, not a prop."

"But how can you show them Buddy Bolden? The man died before Prohibition was repealed."

"Holography," declared Dr. Cabman matter-of-factly. "Our patented virtual reality systems offer not just audio replications, but artificially intelligent imagery to match the music's every note." After letting this sink in for a moment, he invited: "Would you care to see a demonstration?"

Would I! The doctor conducted me through a door at the far end of his office that opened directly onto a bare room where ceiling, floor and all four walls were paneled with a strangely glowing lattice-like surface of embedded light- emitting diodes arranged in continuous parallel sine curves. Millions of expectant little LEDs, pulsing with potential. "Our holodeck," said Dr. Cabman, proud as a papa showing off his newborn. "Welcome to the future of jazz."

Producing a remote control from his vest pocket, the doctor punched its buttons faster than I can speed dial, and the room metamorphosed into what I took to be a faithfully reproduced fin de sicle New Orleans dancehall (possibly the enshrined Funky Butt Hall itself), 3-dimensionally realistic down to its last detail. With a few more button presses, the deliciously disreputable ballroom was populated by a lively crowd of tawdry denizens, men and women in various shades of black and tan and in different stages of inebriation. I was not shocked to find that gambling was going on here, that members of opposite sexes were propositioning one another with brazenly good-natured gusto, and that the aironly a moment ago crisply and impersonally climate-controlledhad suddenly turned sultry with the odors of booze, bodies and bayou vittles. What astonished me, however, was that I could see, touch and smell this luxuriant funkiness as distinctly as if I'd been transported by H.G. Wells's time machine back to the Crescent City with everyone partying like it was 1899.

As we snaked our way to an unoccupied bench, Dr. Cabman explained in techno-babble how he'd mastered the labyrinthine maze of recombinant matter and kinetic energy for this unprecedented interactive simulation. I'm sure he mentioned graphically interfacing positronic replicators, extreme high-definition photon lenses, multiphasic tachyon particle accelerators, inverse filtered graviton equalizers, adaptive force-field tractor beams and dynamically calibrated inertial dampers. But it was all geek to me. "I should add," he added, "our holodeck includes safety protocols to protect users, although we cannot completely insure against minor injuries such as muscle strain or dislocated joints sustained while dancing orhow shall I put this?otherwise exercising."

"First do no harm," I interposed. "Asimov's First Law of Robotics."

"Primum non nocere," the doctor concurred. "And now," he announced, punching more buttons on his remote control and shifting glibly from Latin to French, "le pice de rsistance."

Right on cue, Buddy Bolden and four sidemen flashed onto the holodeck, mounting a small bandstand and brandishing authentic period instruments. To the customers' raucous cheers, the band opened with Bolden's signature "Funky Butt," a tongue-in-cheek (no pun intended) paean to flatulence that included the hilarious refrain "Funky butt, funky butt, take it away!" The crowd went wild.

On this and subsequent numbers, I found audio quality nothing less than sensational: state-of-the-art 21st-century digital fidelity as vividly true as a live performance. And as for the holographic imagery, it went beyond spectacular, rocketing into the realm of metaphysical singularity.

Simulated art? Bosh. This was the real deal, and purists be damned. I was particularly impressed with the programmers' canniness in seamlessly weaving mistakes into the performance. "Verisimilitude," Dr. Cabman confirmed when I commented on the clarinetist's occasional clams. "Turing suggested as early as 1950 that the inherent perfectionism of computers would need to be deliberately impaired in virtual reality systems. Otherwise people feel so inferior, they cannot enjoy the experience."

Wagging my head in amazement, I considered the legal implications of what I was witnessing. "How did you get clearances for these likenesses?" I wondered aloud. "The clientele might be fictitious, but these five musicians were real people."

"Real," Dr. Cabman somewhat testily replied, "but long dead."

"Even so," I quipped good-naturedly, "their rightful heirs and assignees may have lawyered up."

Dr. Cabman was not amused. "I was led to believe you are a serious journalist," he dourly observed. "Perhaps I was misinformed." He abruptly shut down the holodeck and guided me back to his office.

Figuring I'd better cut the crap, I inquired respectfully about his next project. Would it be King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, with the youthful Louis Armstrong on second cornet, at Chicago's Lincoln Gardens in 1923? Diz & Bird with Bud, Max and Mingus at Toronto's Massey Hall in 1953? Ornette, Don Cherry and Paul Bley at L.A.'s Hillcrest Club in 1958?

"J.S. Bach," the doctor looked determined, "concertizing the Well-Tempered Clavier in 1742 at Leipzig's Thomaskirche, just atop what would in due course become his final resting place beneath the altar floor."

Somehow the longhairs always get the last laugh. Still, 2008 was shaping up as Buddy Bolden's best year since 1906. Not only was Cabman Laboratories set to spring this stunning holographic recreation on an unsuspecting public, but Anthony Mackie has enacted the title role, with executive producer Wynton Marsalis providing original music, for the indie biopic Bolden! now in post-production and slated for a 2010 release.

I thanked Dr. Cabman for his time and commended his achievement, speculating that perhaps the Pulitzer Prize in Music might be in order. Without demurring, he summoned the guard to escort me back to my car, and I was soon on my way home.

Gradually, though, after the demo's initial impressiveness wore off, something again started gnawing at me. Later that night, with storms abating, I slept uneasily, dreaming not of Anthony Mackie in Bolden! but of Boris Karloff in The Body Snatcher prowling the Louisiana state asylum at Jackson in search of fresh corpses upon whom might be visited unspeakable scientific investigations. When I awoke with a start at dawn, an accusatory couplet had lodged stubbornly in my mind. "I thought I heard Buddy Bolden say," it went, over and again for the remains of the day. "Funky butt, funky butt, keep that Cabman away!" What do you suppose it could mean?

This blog entry posted by Alan Kurtz.

Tags:

that was a great story.

Voces so demais mesmo sempre buscando o melhor do jazz. Obrigado.

Perhaps if we could really do this, we might be as disappointed as when we re-visit scenes of our childhood and realise that they are nothing like our memory of them. I say keep the mystery - and the legend!

As the child of a superb cornetist, I have a true appreciation for this well-written article. I felt as though I was with Mr. Kurtz and I can't wait to show my husband the reference about "Funky Butt". Thanks for a good read!

Does Dr. Cabman have any plans to release this technology for viewing? This is a very cool idea and could revolutionize music as we know it. I'd love to have a holodeck instead of a home theater.

Good article; enjoyed the creativity! Thanks for making me laugh, and I look forward to hearing more of and about Buddy Bolden.

So what is Cabman Industries' NYSE, NASDQ, AMEX, symbol?