The Jazz.com Blog

January 11, 2009 · 2 comments

The James Brown of Africa (Part One)

My CD collection includes some cherished disks by a band called Franco & Le TPOK Jazz. These releases provide no list of personnel. They offer no recording dates or locations. There is not even a CD booklet, just a single sheet with simple cover art on one side, and blank white space on the other. There is no copyright notice, only an address in Paris, and a list of songs.

Until recently, this is how you typically encountered Franco's music in the West. And you were lucky to have even that much. I got these CDs back in the pre-Internet days, via a small mail order house that brought these disks into the country from God-Knows-Where to serve God-Knows-What market for this kind of music. The mail order house eventually went out of business.

Yet Franco stands out as one of the leading exponents of African music in modern times, and his recordings still enjoy a cult following two decades after his death in 1989. This body of work certainly deserves to be better known, and under better circumstances might have found a larger audience even during the artist's lifetime—but Franco passed away before World Music emerged as an important commercial genre. During his career, he only enjoyed a small dose of the fame that might have come his way in today's global village. Franco made just one tour of the U.S., in 1983, and even that visit was a modest affair. For the most part, his music is still a well-kept secret.

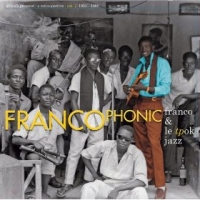

Perhaps the release of Sterns Music's Francophonic, Volume 1: 1953-1980 will go some way toward rectifying this situation. This reissue finally presents Franco's work in a suitably grand setting: a lavishly produced two-disk reissue accompanied by a 46-page book.

Of course, the personnel on these recordings is still mostly a mystery. Francophonic tries to cast some light on the matter, offering a list of around 70 musicians who played with Franco at various points during his 35 year career. But don't expect a track-by-track rundown. As for recording dates: if you get a year, be grateful and don't expect more.

Yet the real mystery here is the music itself, which seems to defy the listener's expectations at every turn. Although Franco's band prominently displayed the word 'Jazz' in its name, the music is not jazz in any conventional sense. Record stores, to the extent that they stock Franco at all (hah!) will put his releases in the African music bin. But play a song of his to a random sampling of your friends, and most (perhaps all) of them will guess that it is Latin music. In fact, if you had to sum up Franco's soukous style in ten words or less you would say that it is the African music that sounds like it comes from Cuba.

A nice definition, but what a strange concept for listeners unacquainted with soukous. The idea of Latin jazz has grown familiar to us, but Latin-African music is something else altogether. I have speculated in other settings, that Latin and African cultural currents possess a residual affinity for each other that is leftover from the Moorish inroads into the Iberian Peninsula starting back in the 8th century. In other words, Latin music was stamped with an African sensibility almost from its birth, and later hybrids of these two musical languages inevitably show their family resemblance.

Still one marvels at the lineage that produced this Caribbean sound in Central Africa. For whatever reasons, Cuban bands such as Trio Matamoros and Sexteto Habanero found a receptive audience in the then Belgian Congo back in the 1930s. As indigenous commercial music styles developed in later years, these role models exerted a strong influence. When Franco began his music career in the 1950s, this Latin-inflected sound was pervasive in popular Congolese music.

But an African rumba is not exactly the same as what you would find in Cuba. On his hit song "AZDA"—inspired, strange to say, by a Volkswagen dealership—Franco builds the performance around a strange five-bar call-and-response pattern that would never fly in Havana. "Marie Naboyi," another long track, starts off with a typical Congolese rumba beat, but abandons it mid-song in a restless search for some other, more insistent groove—the music goes through four distinct moods before coming to an abrupt halt. Other songs, such as "Ku Kisantu Kikwenda Ko" draw on more overtly traditional African material. Yes, a vague pan-global Latin ambiance predominates in this music, but one that is distilled through the distinctive vision of Franco.

This is the end of part one of Ted Gioia's article on Franco and TPOK Jazz. For part two of this article, click here.

Tags:

Franco and Rochereau, Omona Wapi, is a classic. Also check out, if you can find it, an album by another group, The Best "Ambiance".

Yes, Omona Wapi is a fine release. By the way, Sterns has also reissued the music of Tabu Ley Rochereau, whose music also deserves to be better known.