The Jazz.com Blog

January 03, 2009 · 2 comments

When the Best Singing Piano Man Was a Woman

Few critics have a more nuanced understanding of the vocal arts than Will Friedwald, whose works include the highly recommended books Jazz Singing, Sinatra: The Song is You, and Stardust Melodies. Below he writes about the largely unheralded African-American women who followed in the footsteps of Fats Waller. See also Friedwald's profiles of these women for the jazz.com encyclopedia: Cleo Brown, Una Mae Carlisle, Nellie Lutcher and Julia Lee. T.G.

Una Mae Carlisle

“How would you like to submit to a blindfold test, listen to a typical Fats Waller song, then when the bandage was removed find that seated at the keyboard, instead of the 200 pounds of brown-skinned masculinity you expected, was a light, slim, smiling girl?”

Those were the words of critic Leonard Feather, writing in 1937, describing his first experience hearing Una Mae Carlisle. At that time, Feather and his readers may have been surprised to make this discovery - but within a few years, it became obvious to listeners that Fats Waller’s most important followers were female.

It's hard to think of a major male singer-pianist who fills the gap between Waller, who lived from 1904 to 1942, and Nat Cole. From the late thirties through the forties, the best "singing piano man" was, more often than not, a woman.

In the 1930s, Waller sat at the helm of jukebox jazz, in which hundreds of records made by singing musicians were sent to tens of thousands of restaurants, bars, and road houses across the country. Collectively, these jukebox hits raked in millions of nickels, which helped create the modern recording industry.

Compared to the era's increasingly large big bands, it was cheap to hire a six- or seven-piece combo, which made these records big earners for labels, who, at the depths of the Great Depression, sold the discs to juke joints for twenty-five to thirty-five cents a throw. Juke records generally allotted a generous amount of solo space to instrumental soloists, flanked by a vocal chorus by the singing leader.

1934 was the year RCA Victor launched its “Fats Waller and his Rhythm” series, which reinvented the juke-joint genre from the ground up. The success of Waller's “Rhythm” discs, anchored in his jocular, powerful, personality, had a double-pronged effect: like Louis Armstrong before him, he inspired many instrumentalists—piano players in particular—to start singing.

But despite his success, Waller inspired few direct imitators. There was Putney Dandridge on Vocalion, and Bob Howard on Decca, who only occasionally played piano on records, although he was billed as “Fatso Howard” on one of his early recordings. Two of the era's hipper white bandsingers, Dick Robertson and Chick Bullock, also led their own long-running series on Decca and Vocalion, respectively.

Fats, however, did inspire a talented group of women: Cleo Brown, Una Mae Carlisle, Nellie Lutcher and Julia Lee. These four Afro-American women, one of whom—Lee—was actually two years older than Waller—made key contributions not only to juke music, but also to Swing, Big Bands, the Blues, and later the transformation of “race” music into rhythm and blues.

Like Waller, all four were exceptional pianists, and they sang in styles which could be traced back to Waller himself: Cleo Brown sang in a sweet, high voice that recalled Waller in his rare moments of unironic ballad tenderness. Julia Lee, contrastingly, had more of a guttural, blues-based style which suggests Fats at his downest and dirtiest. Like Waller, they were all consistently irreverent, and as much inclined to kid a love song, using humorous asides, as they were to sing it “straight.”

Cleo Brown came in hot on Waller's heels in March of 1935, and was the first of his disciples - male or female - to make a lasting mark on American music. The eighteen sides she recorded in 1935 and 1936 were highly influential, and she was rewarded when, in 1987, she was named a Jazz Master by the National Endowment of The Arts, the nation's highest honor for a jazz musician.

Una Mae Carlisle had an off-and-on romance with Waller, and sang with his big band at New York's Apollo Theater in 1935. But it was critic Leonard Feather who "discovered" her in Paris, and arranged for her to record with British Vocalion in May of 1938. She went on to compose several memorable hits and recorded with many of the Swing Era's greatest instrumentalists, including tenor saxophonist Lester Young.

However, neither of these Femme Followers of Fats could be considered entirely satisfying to listeners: the first fell short in terms of quantity, and the second, occasionally, in terms of quality. However, after World War II, two new heiresses took the stage almost simultaneously to claim Waller's mantle.

Julia Lee and Nellie Lutcher were distinct individuals, but were more alike than they were different. Both were products of the two greatest jazz scenes outside of the Northeast: Lee was from Kansas City, and Lutcher was from New Orleans. Each came to fame recording for Capitol Records in 1946 and 1947. Guided by producer Dave Dexter, himself a Kansas City native, between the two of them they provided Capitol with a steady stream of hits in the late 1940s, and helped established Capitol’s presence in the field then known as “Race Music.”

Lee and Lutcher both worked with groups modeled loosely after Waller’s Rhythm: Lee’s band was billed on the Capitol labels as “Her Boy Friends”; Lutcher’s group was literally credited as “Nellie Lutcher and her Rhythm.” They both also sang a mixture of blues and standards, and further, there was a high sexual content to their work, which was, however, expressed in rather different ways.

The pair were key players as Black music evolved from small group swing and the juke jazz style of the 1930s into what became known as "rhythm and blues." Unfortunately, by 1948, the year Billboard magazine's Jerry Wexler coined that phrase, both of their careers had already peaked.

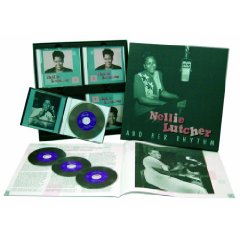

Fortunately for listeners, the works of both have been reissued in lavish boxed sets from the German boutique label Bear Family Records, with elaborate booklets and excellent biographical essays by British scholar Bill Millar.

This blog entry posted by Will Friedwald.

Tags:

2 responses so far

Great article, Will. You could also add Rose Murphy and Hadda Brooks to the list, among others. I managed both Nellie Lutcher and Hadda (and also booked Rose many times) and felt all of the ladies had a performing quality unique to each of them. Nellie told me she was heavily influenced by Cleo Brown and she also credited Hadda's successful recordings on Modern Records (starting in 1945) as being the reason Capitol signed Julia Lee and her (Nellie).

Thanks Alan - stay tuned, both Rose and Hadda will be featured in Will's second installment of this blog, along with Lil Hardin Armstrong and a few other surprises.