The Jazz.com Blog

January 07, 2009 · 0 comments

A Giants Steps: John Coltrane on Atlantic (Part One)

Chris Kelsey, an editor and regular contributor to jazz.com, recently published a smart commentary in this column on Ornette Coleman's controversial Blue Note recordings (see here and here). Now he turns his attention to John Coltrane's work for the Atlantic label, an expansive body of work that is too often lost in the shadows of the tenorist's later recordings for the Impulse label. Below is the first installment of Kelsey's three-part article. T.G.

John Coltranes music was always a work-in-process. Most jazz musicianseven the greatestspend their lives refining one style. Coltrane was an exception. He never ceased expanding and evolving. There were no stopping points in his music, only points of departure.

Some choose to see Tranes development simply as a manifestation of the cultural tumult of the 1960s. It was, to some extent, but its a mistake to interpret it as being inspired by some 60s-radical desire to be seen as different. To imply as much, diminishes his accomplishments, makes it seem as if he were some jazz equivalent of Wavy Gravy or Timothy Leary.

Coltrane was no hippie; he was an inveterate explorer. Change was a constant in his music because he was hard-wired that way. Coltrane moved because he couldnt stand still. There was too much to do, andas he was to discovernot enough time in which to do it.

Naturally, his recordings reflect that state of constant flux. Coltranes 50s recordings with Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk reflect tremendous growth, but his evolution began to truly accelerate in 1959the year he began putting together his own band (a process that involved much trial-and-error), and began recording for Atlantic Records. It was a period of enormous change for Coltrane. By the time he had finished at Atlantic in 1961, he had metamorphosed from an ultra-progressive bopper to a musician concerned with redefining jazzs very boundaries.

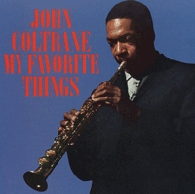

Among his more easily identifiable accomplishments during those 28 months: he conceived and recorded some of the mostly harmonically elaborate jazz compositions ever written; recorded a signature tune ("My Favorite Things") that became something of a hit song, and in the process helped popularize a modal concept of playing jazz; reclaimed a long-neglected instrument (the soprano sax) for jazz; made a significant move in the direction of the avant-garde by recording with free jazzs top trumpeter, Don Cherry; refined saxophone techniques that would affect the way the horn would be played thereafter; and began incorporating techniques of world music into his concept. Pre-Atlantic, Coltrane was a potentially great, but relatively conventional, jazz musician. Post-Atlantic, he was well on his way to becoming one of the most influential jazz musicians of his or any other time.

By 1959, Coltrane was ready in every way to leave the employ of Miles Davis and form his own band. He was mentally and physically healthy. He was highly regarded by both critics and the jazz public. Most importantly, he had musical ideas he could only work on with his own group. Yet, while hed led many recording sessions, mostly for Prestige, he had not yet taken the crucial step of leaving Davis and striking out on his own. Of course, leaving the most successful small group in jazz wasn't a decision he took lightly. Davis didnt want him to go, and Coltrane surely enjoyed the financial security the gig provided. In any event, the end of his time with Davis overlapped with the beginning of his period at Atlantic.

Coltranes first recordings for Atlantic resulted in Bags and Trane, recorded on January 15, 1959 in New York City. Coltrane co-led the date with the Modern Jazz Quartets vibist, Milt Jackson. The album reflects the grittier sensibility Jackson usually adopted when playing apart from the more consciously refined MJQ. The repertoire consisted mostly of standards and blues, along with Charlie Parkers up-tempo flag-waver, "Bebop"a nod to a jazz era that was, by then, already receding into the mists. The leaders were joined by pianist Hank Jones, bassist Paul Chambers, and Jacksons MJQ band mate, drummer Connie Kay. Its a fine record, hard-swinging and full of top-notch playing. In terms of where Coltrane was at the time, however, its backward-looking. Hed been-there-done-that, and was manifestly ready to move on, as his next dates for Atlantic made clear.

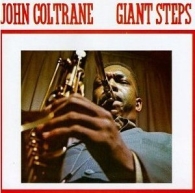

Giant Steps, Coltranes first actual release for Atlantic (Bags and Trane wouldnt be issued until 1961), gave a more accurate picture of where he was as an artist. The recording of the album was actually a two-part affair. The first session took place on April 1, 1959 in New York City, with a band consisting of pianist Cedar Walton, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Lex Humphries. The quartet recorded several takes of three Coltrane originalsGiant Steps, Naima, and Like Sonnybut none were deemed satisfactory by Coltrane. The music from this session remained unreleased until several years after Coltranes death.

A second session was convened on May 4 and 5, 1959, with a substantially different cast. Paul Chambers returned, but Walton was replaced by Tommy Flanagan, and Humphries by Art Taylor. Over the span of two days the group recorded all six tunes that ended up on the album, plus oneSweet Siouxthat was rejected and later lost.

Giant Steps was a landmark. Not only did it present the apotheosis of his experiments with harmonic complexity (Countdown and the title track); more than any of his prior albums, it showcased his compositions, among them Naima, a pedal-point-based ballad; Cousin Mary, an ingeniously altered blues; and Mr. P.C. a fast minor blues dedicated to bassist Chambers. The absence here of songs from the standard jazz repertoire is telling. Coltrane was much less interested in playing music written by others. Henceforth, he would mostly supply his own contexts, which would be inextricably linked to his evolving concept of improvisation.

This is the end of the first installment of Chris Kelsey's three-part article on John Coltrane's Atlantic years. Click here to read part two of this article.

Tags:

Comments are closed.