The Jazz.com Blog

October 12, 2009 · 1 comment

The Once and Future Strings (Part Two)

Bill Barnes continues his three-part article on the role of guitar in jazz below. For the first installment, click here. Click here for part three. T.G.

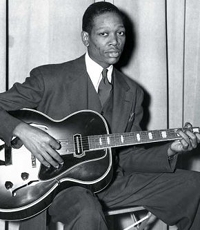

Los Angeles, 1939: On the bandstand a slender young black man from Oklahoma wields an archtop acoustic guitar adorned with a magnetic pickup connected to a primitive tube amplifier, an odd looking box slightly out of place on a stage crowded with horns and music stands.

With a sideways glance at the quirky setup, the bandleader brings his clarinet to his lips and swings into the head of "Rose Room." The horn section blares, the drums crash and boom; the guitarist takes his chorus. Suddenly piercing, bell-clear solo lines spring from the grill of the tiny amplifier as the Gibson ES-150 shouts defiantly over the din of the orchestra in distinctively horn-like phrases: "I am jazz guitar and I have something to say!"

The electronically enhanced soloist, Charlie Christian, would die of tuberculosis a few years later, but his legacy would live on. Of course, Christian was not the first jazz guitar player, nor was he unique in his ability to play intricate single-line solos. Eddie Lang had already forged a reputation for innovative solo technique on the archtop. Across the Atlantic, Django Reinhardt, Oscar Aleman and Pierre Baro Ferret were laying the foundation of Hot Club swing and jazz Manouche on Maccaferri-designed Selmers and the not-so-heavy metal Regulators. However, Christian was successful in bringing the amplified guitar to the forefront as a solo instrument, opening the door a little wider for subsequent generations of guitarists.

The evolution of jazz guitar continued with legendary players such as Barney Kessel, Tal Farlow, Johnny Smith, Grant Green, Kenny Burrell, Jimmy Raney and Wes Montgomery. Through their fingers, the inspired elocution of finely crafted ideas defined the parameters of the instrument. At the same time, the physical development of the guitar also helped define the parameters of jazz. The amplified acoustic guitar could deliver flurries of notes cutting through the loudest horn sections, but it had a limited capacity for wailing; that is, until two musical pioneers, Les Paul and Leo Fender independently produced the next step in the instruments evolutionthe solid body electric.

Paradoxically, this innovation eliminated the feedback problems associated with the hollow body, while giving the guitar the ability to sustain notes and scream at inhuman decibel levels. As the solid body came into its own, elements of blues, rock and roll and funk broadened the role of the guitar in shaping the nature of the art.

With Gibsons Les Paul model, British guitarist John McLaughlin added a bold, if slightly metallic voice to the groundbreaking Miles Davis album, Bitches Brew, and an electrified intensity to the first two Tony Williams Lifetime recordings. His Mahavishnu Orchestra further expanded the boundaries and permanently blurred the line between jazz and rock.

Chick Coreas Return to Forever ensemble followed suit with the dissonant and occasionally chaotic Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy featuring tortured, heartfelt solo work by guitarist Bill Connors and the white-hot sustain of his Les Paul Custom. Meanwhile, sixties blues and rock innovators Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Winter and others had pushed the edge of the envelope for Leo Fenders Stratocasters, creating new dynamics which would leach into the approaching fusion movement.

But the solid body would not completely dominate: McLaughlin also helped raise the acoustic bar in an unforgettable duet with Larry Coryell on the visionary milestone recording Spaces and featured the transducer-enhanced Ovation flattop on his My Goals Beyond. Pat Martino proved that the archtop still held a few surprises with the release of his cultural amalgam, East. Other mainstream heavyweights like Joe Pass, Jim Hall, Herb Ellis, Bucky Pizzarelli and George Barnes would continue to keep faith with the hollow body jazz box. George Benson would utilize its warm, bubbly sound to achieve unprecedented commercial success.

In the following decades, the once supportive rhythm instrument took center stage as guitar wizards like Steve Khan, John Scofield, Mike Stern, Pat Metheny and Larry Carlton became pied pipers winning over thousands of new jazz fans among young listeners. Blues men and rockers like Duane Allman, Jeff Beck and Carlos Santana reached across the aisle for brief forays into the jazz genre. As audio technology evolved and CDs became the delivery system, a wave of new players vied for attention. At the same time, music trends were rapidly shifting and, although players such as Russell Malone, Mark Whitfield, Kurt Rosenwinkel and Ron Afif rose to prominence, there seemed to be less room at the top.

Then, along came the Gypsies. In the nineties, Sinti musicians such as Bireli Lagrene, Jimmy Rosenberg and Angelo Debarre rode the first wave of enthusiasm for the rediscovered music of Django Reinhardt and the Hot Club Swing Revival took hold. Gypsy jazz is still growing in popularity, even as some of its major practitioners are breaking away from its tight pompe form in favor of mainstream, bop and cool idioms. But the Gypsy technique has had a major impact on European players like Robin Nolan, Andreas berg and Jon Larsen, and has been working its way into the musical vocabulary on this side of the Atlantic as well, with versatile session players John Jorgenson and Howard Alden and French guitarist Stephane Wrembel as its leading protagonists.

Currently there are so many wonderful jazz guitarists on the forefront that it would take volumes to give them justice. But the shifting dynamics of a shrinking, interconnected world and the resultant cultural exchanges have created a new synergy, changing the nature of how we experience music. Just as the last Broadway production of Cabaret had audience members seated at tables onstage as part of the act, todays jazz audience is assuming an increasingly participatory role as jazz camps, clinics and interactive websites further integrate the separate worlds of performer and patron. The guitars unique properties give it a critical role in this increasingly evolving jazz environment.

This blog entry, by Bill Barnes, is the second section of his three-part article on the state of the guitar. Click here for part three.

Tags:

This was a very enlightening article fo me. I had never considered that the problems of feed back in amplification of guitar led to the solid body electric. I was also unaware that the solid body guitar had such an impact of playing style and the formation of new genre's of music.