The Jazz.com Blog

October 28, 2009 · 0 comments

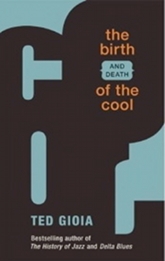

The Birth (and Death) of the Cool

This week marks the publication of my new book, The Birth (and Death) of the Cool. With the permission of the publisher, I am sharing an extract below. Also, note that I will be making an appearance in the Los Angeles area this Friday, October 30, at Book Soup, at 8818 Sunset Boulevard, at 7 PM. T.G.

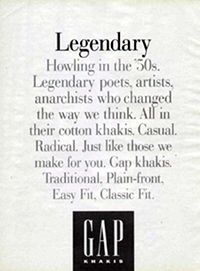

For a long time, coolness has been measured primarily at the cash register. So much so, that the word cool today is used most often to describe a gadget or a product or something else available for sale. Back in the 1950s, the term might be affixed to a person or a style of music or an attitude. But with each passing year, cool is less and less a personal vibe and more an attribute of merchandise.

A Google search for cool and iPod comes back with ten million hits. You get the idea; of course you do, it's pounded into your head a thousand times a day by every marketing message that tries to co-opt coolness. This depersonalization and commoditization of the cool has perhaps been its greatest success�but also a leading cause of its decline. Cool has been a great concept and has served its corporate bosses loyally for as long as it could, but now it is approaching its point of exhaustion.

A postcool society? You may think that strange, but here is something stranger: the people who are leading the way are those who, a few years ago, would have stood out as the coolest of the cool. The cool is crumbling from the inside. The trendsetters are now the most vehement in moving beyond the cool. And for that very reason, the retrenching of the cool is one trend that will not be reversed any time soon. This postcool attitude is not just another style, but a rejection of the stylized. It is not just another trend, but a distaste for trendiness. It is not just another pose, but a dismissal of the poseurs.

And what is that new worldview? What comes after the cool? To some extent, life after cool will remind us of what life was like before cool came on the scene. Cool was defined by its reliance on image and irony, by its artifice and playful fluidity. It was marked, above all, by an outward focus on trends and fashions. The notion of lifestyle�a term that hardly existed outside of academic literature during the first half of the twentieth century�became of paramount import during the Age of Cool, and the idea that one could shape one�s persona and way of living as though they were works of art (a foreign concept to most people during the Great Depression) became widespread.

Postcool, in contrast, is built on a new earnestness and directness, a celebration of simplicity and authenticity. Irony is out; plainspokenness is in. The natural and down-to-earth are preferred to the glitzy and fashionable. The real is valued above the contrived, honesty above artifice. Communications�from the simple text message to the spin-doctoring of prominent pundits on the boob tube�are quicker and to the point. Postcool is less exciting than cool, but more practical and results oriented. It�s less malleable and fluid, but far more predictable in its behavior patterns.

Yet the shift to a postcool mentality is not without its downsides. Above all, many problems are created when society loses its cool. The directness and bluntness of postcool life are only a step away from outright hostility and confrontation. We already see this in talk radio and cable television and other spheres of social interaction, where the decibel levels quickly rise and conversations easily collapse into shouting matches. Talk radio becomes scream radio. Town hall meetings turn into WWE free-for-alls. Back in the days of cool, indirect and ironic styles of communication were the norm, and ways of interacting were more stylized and often fanciful. As a result, social exchanges were slower to escalate into confrontation and denunciation. But postcool prides itself on its directness and is suspicious of rhetorical flourishes that soften our interactions. In short, life will be rougher and tougher after cool has left the building.

And the postcool lifestyle? Actually, there is more than one. Of course, many people nowadays are simply burnt out on the hip and stylish, opting out of cool�s glitzy promises by choice or necessity. If cool were a credit card, these people maxed out long ago and are now on a different path. But a growing number of individuals have deeply set values and priorities that put them at odds with the cool. Many are tuned into concepts of sustainability and eco-friendly living; these people inevitably find that green values are incompatible with the increasingly consumption-oriented precepts of cool. Others pursue what were once called alternative lifestyles, but they aren�t so alternative anymore when tens of millions of people embrace them. Ways of living, previously on the fringe and captured under the catchall rubric New Age have now gone mainstream; they encompass everything from meditation to macrobiotics, but share the confidence that they have gone beyond fashionability and cool attitudes.

Still other builders of the postcool society have less flamboyant ways of rebelling against trendiness�in fact, their lives are often so nondescript that the media struggles with labels, such as �soccer moms� or �NASCAR dads,� in their attempts to comprehend their very unvoguish values. A host of religious movements promise the same thing: check out the growing chorus of believers who urge us to be uncool for Jesus�or Buddha or Muhammad or some other spiritual force outside the gravitational pull of pop culture. Meanwhile, others look to a more biological type of redemption, seeking a pure and healthy life; and though these folks may be ignorant of the latest fads and fashions, they are excited by words like organic, unprocessed, unadulterated�a fixation with the natural that was once on the fringe, but is increasingly part of the mainstream. A separate constituency adopts a political stance in their opposition to cool, rebelling against Nike and other merchants of fashionability as part of protest against cultural and economic imperialism. This shift in the Zeitgeist, as we shall see, cuts across all political ideologies and demographic categories.

But, most of all, we see the death of cool in a pervasive change in attitude sweeping all segments of society. We see it in a marked lessening of irony and sarcasm and cooler-than-thou vanity in the public sphere�behavior patterns that dominated the last half century�and their replacement by a new earnestness, almost a cult of sincerity. We see it in the rapid growth in styles of art and ways of living that emphasize authenticity, simplicity, and getting in touch with nature and natural ways. We see it in a return to roots, in which individuals, families, and communities find renewed meaning in shared rituals and traditions. We see it in a growing distaste for marketing, hype, and exaggerated forms of expression, and a preference for stick-to-the-facts honesty. These down-to-earth attitudes have always been present, and back in the 1930s and �40s they actually were dominant in social and community life. But with the media-fed cult of the cool, they were pushed to the sidelines.

Guess what? They are coming back stronger than ever. Such old-fashioned ways are easy enough to ridicule�and many are quick to point out that authenticity and earnestness are the slipperiest of concepts�yet these ideas are becoming the powerful forces again in public discourse and private lives. Who can be surprised, when Merriam-Webster reports that the word most frequently looked up in its online dictionary is integrity? This is exactly what people are looking for today�and not just in the dictionary.

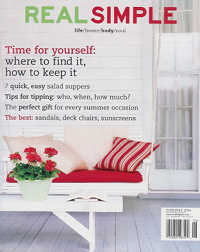

A comparison between two magazines, with their opposed mind-sets and diverging histories, gives us a flavor of this seismic shift in attitudes. In 1999, Tina Brown, former editor of trendsetting Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, and Tatler, put together what promised to be the biggest�and coolest�magazine launch in history. Supported by a host of high-profile people and enormous financial resources, Brown raised the curtain on Talk with a blowout party at the Statue of Liberty�an event described by one newspaper as �the most opulent ever thrown� in the history of Manhattan media. With Lady Liberty looking on, the A-list of socialites, power brokers, and arbiters of taste�Madonna, Henry Kissinger, Salman Rushdie, Quentin Tarantino, Paul Newman, Kate Moss, and Matthew Broderick, among others�gathered for what seemed to be a defining moment in the history of cool. Give me your huddled millionaires yearning to eat Brie. You couldn�t get hipper than this, and celebrities clamored to get their names and photos in the pages of the magazine that was poised to define fashionability for the new millennium.

And then? Well, the magazine went down in a spectacular manner. True, it attracted advertisers, and name writers, and all the beautiful people featured in the articles�but it couldn�t interest readers, who looked at Talk and just yawned. The magazine closed its doors two and a half years after the Statue of Liberty bash. The harder Brown strived to be cool, the less people paid attention. Certainly it wasn�t for lack of investment capital. Talk was not cheap. It burned through $50 million�an extraordinary amount for a periodical�during its brief life. Despite the massive hype, circulation peaked at a modest 670,000.

Meanwhile, at virtually the same time that Brown was flogging Talk, an absurdly low-profile magazine took life with a very understated name. Called Real Simple, this periodical ignored coolness at every step, presenting itself with an austerity that seemed to defy every rule of media survival. Its goal was to provide �beautiful, actionable solutions for simplifying every aspect of your life.� Huh? You need a magazine for that? Few in the media paid attention, and those who did often laughed at the concept. Some derided the periodical as an �aphorism in search of an audience.� Even its editor happily proclaimed �this magazine doesn�t have a personality.� Yet Real Simple flourished while Talk faltered, pushing its circulation up to two million and now occupying the same wire racks at the supermarket checkout stand that once held Tina Brown�s oh-so-cool paean to the trend of the month. In 2006, Real Simple made the move to television with the launch of a companion show on PBS. Brown had dreamed of a media empire with offshoots from her magazine, but the ascetic periodical with the strange, understated name is now the player who is spreading into new markets.

This is an extract from The Birth (and Death) of the Cool, a new book by Ted Gioia published by Speck Press. All rights reserved.

Tags:

Comments are closed.