The Jazz.com Blog

February 18, 2009 · 0 comments

The King of Western Swing (Part 2)

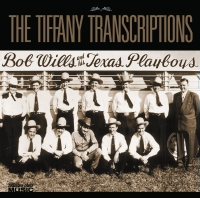

Below is the second installment of my three-part article on Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys, a pioneering ensemble in merging jazz and country music styles. The occasion for this essay is the release last month of The Tiffany Transcriptions, which captures some of the band's finest work from the post-WWII era. For part one of this article, click here. T.G.

Bob Wills, the great master of Western Swing, was not an overnight success. Born as James Robert Wills near Kosse, Texas in 1905, he was the oldest of ten children. The future country jazz star spent his early years picking cotton, and hopping trains from town to town. He trained to be a barber in his 20s, got married, and moved to Turkey, Texas, and then settled in Fort Worth in 1929. At an age when most pop music icons are strutting the stage, Wills was still offering a shave and haircut for two bits.

But he kept up his fiddling, which he had learned at home as a youngster. Wills' father, John Tompkins Wills, had been statewide champion fiddler, and the family had its own band that held dances in their home. "I've seen them move the furniture out of these four rooms into the kitchen and onto the porch," a neighbor told Wills's biographer Charles R. Townsend as she took him on a tour of the former family hone, "and dance in all four rooms."

Wills heard black music at a very early age and developed a taste for jazz and blues that clearly shaped his later work as a bandleader. Wills once rode fifty miles on horseback in order to see Bessie Smith perform. "She was about the greatest thing that I ever heard," Wills would later enthuse. "In fact, there is no doubt about it. She was the greatest thing I ever heard." Wills also was a fan of dixieland jazz, and the key elements of this style—syncopation, improvisation, swing, and a marked informality and exuberance—became essential to his own conception of music.

In Fort Worth, Wills worked in medicine shows, and performed on the radio. Wills's band won a fiddle competition in front of an audience of 7,000, and he began to make a name for himself—not just for his musical skills, but also for his stage presence, his easy-going banter and sure instincts as an entertainer.

These qualities come to the fore on the recent CD box set The Tiffany Transcriptions, in which Wills keeps up a constant dialogue with his radio audience throughout each song. "Come in Brother Bernard," he announces in "Milk Cow Blues." "Ladies and gentleman that is Junior Barnard and his standard guitar. [Long pause.] That is, two more payments and it will be his."

During the 1930s, Wills' settings changed from time to time—fans would find him with the "Fiddle Boys" or "Light Crust Doughboys" and he eventually settled into a comfortable niche as leader of the "Texas Playboys." Wills also changed his home base, moving to Waco then to Oklahoma City and Tulsa. As the decade progressed, Wills' music became even jazzier. He added horns and drums, and paid close attention to the growing popularity of big band jazz. As American popular music got hotter and more swinging, Wills adapted the Playboy's stylings to match the prevailing mood.

Although drums have found their way into all styles of popular music, they were not common in country bands at the time Wills began relying on them in his rhythm section. A few years later he would cause a stir by bringing them to the Grand Ole Opry, where traditionalists were scandalized. The staff even tried to prevent him from bringing the drums on stage. Today country bands have drummers—so you can be the judge of who won that fight.

Wills built a loyal audience during the 1930s, but his big break came when the Playboys recorded "New San Antonio Rose" in 1940. He had recorded "San Antonio Rose" as a fiddle instrumental number in 1938, but this new version grafted a swing jazz sensibility on to the country foundation. This would prove to be the quintessential Western Swing song, and would become a million seller. For a brief moment it seemed as if jazz and country traditions—the United States' two most distinctive indigenous forms of popular music—were about to merge into some exciting new hybrid that would change the face of popular music.

The Tiffany Transcriptions capture Wills at his loosest and most informal. The band has shed most of its hornplayers (at its peak the Playboys boasted 23 members) and emphasizes the strings. But this is no return to the Carter Family. Wills is definitely plugged in, and we find him featuring electric guitar and electric mandolin and steel guitar. These days the idea that you can build a band around electric guitar is a commonplace, but in the 1940s electric guitar was still a novelty sound in American popular music. Wills, however, places it at the center of his music in these radio broadcasts.

There is some heavy irony here—namely that an artist many would have dismissed as too old-timey back when these sides were recorded, would be anticipating the music all the youngsters would be listening to a decade later. A few critics (most notably Nick Tosches) have tried to trace the country roots of rock-and-roll, but these postwar Wills recordings are a good place for fans to start in trying to understand the linkages.

Those who have spent some time with Wills' music will hardly be surprised to learn that when Chuck Berry recorded "Maybellene" in 1955, he looked back to a recording by the Texas Playboys for inspiration. Future rocker Bill Haley was also inspired by this style of music, and in the late 1940s led a band called the 4 Aces of Western Swing. And, yes, Bob Wills did make it into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, but not until he had been dead almost 25 years. But better late than never.

What about the various jazz-oriented halls of fame, at Downbeat and elsewhere? Do they recognize Will's achievements? Maybe, it's better not to ask . . .

This is the end of part two of Ted Gioia's article on Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys. Click here for the third and final part of this article.

Tags:

Comments are closed.