The Jazz.com Blog

February 08, 2009 · 4 comments

Jazz's First Avant-Gardist

Half a century ago, Ornette Coleman bit into the Big Apple, turning the jazz world upside down, inside out, and every which way including sideways. Yet jazz.com's resident curmudgeon now argues that the avant-garde did not begin with Ornette, Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra or other seers of the 1950s.

Follow Alan Kurtz's tortured logic, and you arrive at a most unlikely candidate for granddaddy of the avant-garde. Even if you don't buy the argument (and if you do, we have some prime real estate for sale in the Everglades with a slight drainage problem), you may be perversely fascinated by this latest jailbreak of fugitive ideas from our web site's most twisted mind. Readers are invited to comment or nominate their own candidates, either below or by email to editor@jazz.com. T.G.

When I arrived at her modest bungalow around noon, my trusty medium Madame Bullshitsky was just opening for business. Naturally she claimed I was expected. What kind of psychic would be surprised to see someone? Ushered into her darkened parlor, I could soon make out the familiar disarray of tarot cards, rolling papers, and books on music theory.

After she'd settled behind her crystal ball (which she once confided to me was mostly for show, to impress the tourists; although she insisted it helped her focus), I explained my quandary. Since Wynton Marsalis is otherwise occupied, famed filmmaker Ken Burns has shrewdly retained me as a consultant on the jazz portion of his upcoming documentary, Avant-Garde: The Prequel. Naturally I accepted this important assignment with undue humility. The problem was, as my deadline loomed, I still hadn't identified jazz's first avant-gardist. Burns wanted a seminal figure on whom he could fixate as he'd done with Louis Armstrong in an earlier project, The Civil War: Between Jazz and Baseball.

To my relief, Madame B. didn't hesitate for an instant. "I know exactly what you need," she declared in her thick Bulgarian accent. "A sance with the appropriate phantasms will set you back $300." I assured her that price was no obstacle, since I'd already optioned an account of this adventure with jazz.com. "Ted Gioia will pick up the tab," I confidently predicted.

Lapsing quickly into a pre-tuned trance state, Madame B. exercised self-hypnotic regression to contact the spirit world. "Alright," she said when ready. "Where shall we start?"

Determined to probe deeper than the Cecil-Come-Lately experimentalism of the 1950s, I instructed her to work backward among recordings dating no later than 1949.

"I hear a clarinet," she muttered in due course. Clarinet? Avant-garde? In 1949? That couldn't be right. "Yes," she maintained. "The name comes hazily. George's buddy." Of course! "A Bird in Igor's Yard" from April 1949, composed by George Russell and waxed by Buddy DeFranco. Highly advanced stuff.

Satisfied that we were on the right track, I urged her to go back farther in time. "Very strange," she said. "I hear a small combo, and they sound well rehearsed. But each man is playing in his own private key." That could only be Lennie Tristano, who did indeed wax "Wow" in March and "Intuition" in May of 1949.

I told her to continue regressing. Transfixed, she turned a whiter shade of pale. Fear grotesquely contorted her face. "A tall nobleman spreads his arms, as grandly as an eagle in flight. Loud music. Many brass. Much dissonance. Someone has orchestrated Hieronymus Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delight." No doubt about it: Stan Kenton conducting Bob Graettinger's "Thermopylae" (December 1947). Kenton's "Monotony" from that October was nowhere near as scary, but also quite progressive.

"Go back more," I instructed. As fright fled from her face, she groped for words to describe what next she heard. "Bop noir," she said uncertainly, then decided that was right after all. "Yes, bop noir," she reiterated with conviction. Surely she meant Thelonious Monk's original "'Round Midnight" (November 1947). Now we were getting somewhere.

"Keep going," I implored. Her mouth now assumed a wry grin, and she couldn't suppress a chuckle. "Oh, yes," she said knowingly. "I sense the Russian's hand alright. He has these fine musicians playing that which they do not understand. He demands cash on the barrelhead." Oh, so now we were up against the composer who'd sparked riots in Parisian streets in 1913 and whose less-than-riotous "Ebony Concerto" was recorded by Woody Herman in 1946. Igor Stravinsky himself. "He says it's pronounced Eye-gore," Madame B. sharply corrected me.

Before I could fully process this, she'd moved on. "A peer and his sweet pea," said Madame B., "entertain roughnecks in a principality far from Carnegie Hall." Had to be the Duke & Billy Strayhorn rummaging through "Tonk" (1946), the quirkiest heirloom in all Ellingtoniaa wondrous anomaly.

Before I could fully process this, she'd moved on. "A peer and his sweet pea," said Madame B., "entertain roughnecks in a principality far from Carnegie Hall." Had to be the Duke & Billy Strayhorn rummaging through "Tonk" (1946), the quirkiest heirloom in all Ellingtoniaa wondrous anomaly.

"What's next?" I prodded. "Or rather, what's before?" Attending to her spectral familiars, my medium with a message began giggling. "More pranksters," she chortled. "They're pulling our legs. Or," she seemed to reconsider, listening closer to that distant music mere mortals could not hear, "possibly not. At first you think it's like a clown playing Hamlet. Then you realize it's a serious actor playing a clown playing Hamlet. The joke's on us." I'd seldom seen Madame B. so engaged. But then, Raymond Scott's "Powerhouse" (1937) will do that to even the most stoical soul.

Suddenly she began gulping for air. "We are in the water," she gasped. "A cephalopod with eight arms is playing the marimba." That'd be Red Norvo's "Dance of the Octopus" (1933), an early case of surrealist jazz. For her own safety, I ordered Madame B. to return to land and go back farther in time.

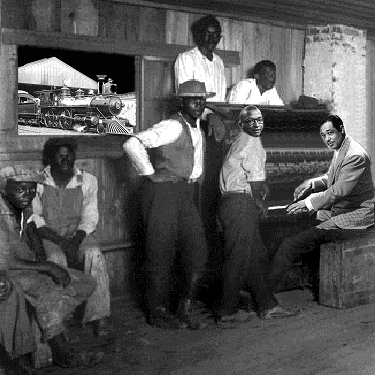

She breathed easier at once. "Hot stuff coming," she advised, obviously on terra firma. "People hang from high windows tossing tickertape at a dashing young man with wings. A chubby bambino hits grapefruit with a bat. A mechanic smears grease on his face, then sings on bended knee about his jammies." Madame B. appeared to be losing her connection. "Disjointed music," she said. "Jagged edges. The Commissioner is displeased. He sharply claps his hands!" And with that, she fell instantly out of her trance. "Credit card or ATM?" she inquired.

This timely little visit was positively worth Gioia's $300. Fulfilling my quest for Artist Zero would now be just a matter of deciphering Madame B.'s somewhat cryptic clues. (She did offer an option with less crypticism, but that would've run $500, and I was not about to squander jazz.com's money.)

Earnestly pledging that Doris would cut a check for the overnight pouch, I took the Madame's leave. On the clogged freeway to my office, I pondered her metaphors. The winged young man strewn with tickertape must be Charles Lindbergh. A chubby bambino smashing grapefruit with a bat was of course Babe Ruth. And the mechanic in greasepaint, singing on bended knee, could only be the deplorable Al Jolson. Yes, this was undoubtedly New York City in 1927.

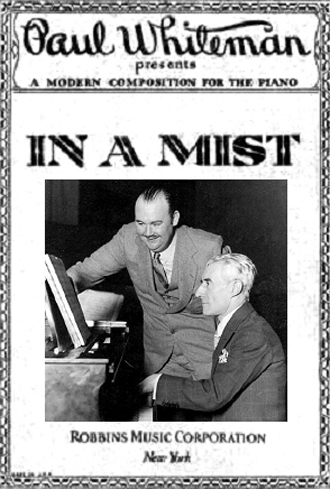

However, the disjointed music that displeased the Commissioner left me momentarily stumped. It took me hours to unravel that one. But it was right there staring me in the face. The 1920s' most popular bandleader, a classical violinist turned symphonic jazz commandant, is best remembered today for commissioning George Gershwin's glorious Rhapsody in Blue, which he then presented (with its composer at the piano) at its premiere during An Experiment in Modern Music in 1924.

This same "commissioner," if you will, in the Year of Lost Chords 1927 hired pioneering jazz arranger Don Redman to orchestrate a Fats Waller tune. Alas, the commissioner's normally accomplished band, rushing the tempo and flubbing notes, butchered Redman's "Whiteman Stomp." Thankfully, that same year the legendary Fletcher Henderson recorded it to better effect.

Wacky as it sounds, then, jazz's first avant-gardist, the prophet who put experimentalism on the map and was so far ahead of his time that we still haven't caught up, turns out to be none other than (may I push the envelope, please?): Paul Whiteman.

Some will object that jazz was always avant-garde, and needed no Whiteman to set it free. Yet it's equally valid to say that jazz, however contemporary it may have seemed in the early 20th century, did not become musically modern until the advent of bebop. Indeed, we tend to forget that during the mid-'40s, before the descriptor "bebop" took hold, the emerging music was called Modern Jazz, to distinguish it from the earlier traditional forms.

Which makes Whiteman's evolution from classical violinist to hot bandleader to symphonic jazzman to Impressionist devotee to avant-gardist all the more remarkable. Notwithstanding his enormous success during the Roaring '20s, Whiteman's artistic direction veered unexpectedly following the Wall Street Crash of 1929. He abandoned his Impressionist phaseduring which he'd introduced Maurice Ravel to "In A Mist," a composition for solo piano by Bix Beiderbecke (Whiteman's ill-fated cornetist)and traveled to Hollywood to star in Universal Pictures' Technicolor musical King of Jazz (1930). On its face, that appeared to be a reversion to commercialism. But it was there that Whiteman fell under the influence (or was it spell?) of Universal's creepy import, Hungarian actor Bla Lugosi, who was just then transferring to the silver screen his Broadway sensation Dracula.

Paul Whiteman thereupon himself caused a sensation. Adopting the nom de cinema "Oliver Hardy," the artist formerly known as Whiteman generated widespread confusion, especially among the fellow already named Oliver Hardy, by now well established as a comic actor. The fact that the two men, born two years apart, looked enough alike to be twins instilled further consternation. But this was exactly what the new Oliver Hardy intended. (To keep the story straight, I shall continue to call him Whiteman.) Assuming a comedic guise was tactically brilliant, since it disarmed bourgeois objections to his increasingly experimental music.

Whiteman's masterpiece during this period was unquestionably The Music Box (1932), a 29-minute film in which Laurel & Hardy (the real one) reenact the legend of Sisyphus. Cast as hapless piano movers, the comedians must trundle said instrument up an impossibly steep outdoor stairway to a hilltop destination, where it will be a young wife's surprise birthday gift to her self-important professorial husband who hates and despises pianos. The film's running gag is that L&H keep losing their grip on the castered wooden crate encasing the piano, which then careens out of control down the concrete stairs and comes to rest only when it reaches the faraway street at the bottom of the hill.

Somehow, Paul Whiteman's sly genius perceived in this cinematic setup an unparalleled opportunity to introduce millions of moviegoersmen, women, and children aliketo avant-garde jazz.

Whiteman did not concern himself with the script's diegetic music, namely solo piano renditions of old standbys "Turkey In the Straw," "Dixie" and "The Star-Spangled Banner." That pedestrian chore was handled by Marvin Hatley, longtime music director of the Hal Roach studio and composer of Laurel & Hardy's quaint theme, "Dance of the Cuckoos."

Rather, Whiteman created the jazzy cacophony emanating from within the crate as the pianowith its damper pedal set, for some unexplained but miraculous reason, to full sustainrepeatedly makes its jostling and jouncing way unescorted down the long stairs to the waiting street. Scored as a duet for piano and tubular bells, Whiteman's 12-minute piece "Losing Our Grip" was as bold in its visionary insight as it was stunning in its execution.

Admittedly one detects the influence of Whiteman's younger contemporary, ultra-modernist composer Henry Cowell. While still in his teens, Cowell had written " Dynamic Motion" (1916) to investigate the expressive possibilities of the solo piano tone cluster, an outlandish technique in which the keyboardist, like an untrained young child flailing for the first time at the family upright, uses flat-hand and forearm smashes to pound out massively dissonant secundal and chromatic chords. This innovation so impressed Bla Bartk that he tried unsuccessfully to secure its European patent. Truly, as his protg John Cage would later remark, Henry Cowell was "the open sesame for new music in America."

Yet not even Cowell could've conceived Whiteman's most inspired stroke. For the soundtrack sessions, and at his own expense, Whiteman imported the incomparable Parisian jazz chimes player Quasimodo de Notre-Dame, who'd jammed with a juvenile Django when the Gypsy plectrist was still playing mostly banjo, as attested by their historic recording "C'est les Cloches, Vous Savez" ("It's the Bells, You Know"). The superbly inventive chimist, nicknamed Q., proved pivotal in realizing the full potential of Whiteman's piece.

Also contributing to the mix are the percussive sounds of an actual crate bounding over cement steps, recorded on location during filming. Whiteman ingeniously incorporates these noises into an overall rhythmic framework unmistakably derived from jazz.

Regrettably, what we hear is not a continuous performance, since it is necessarily interrupted by bits of comedic business from Laurel & Hardy. Yet "Losing Our Grip" is nonetheless the indisputable wellspring of avant-garde jazz, anticipating Cecil Taylor by three decades.

It's difficult to either describe my elation or fix the precise Eureka! moment upon realizing that I'd finally identified jazz's first avant-gardist. Candidly, I don't even recall phoning Ken Burns at what must've been for him an ungodly hour. All I know for sure is that when I got him on the line, I broke the news without preamble, saying simply and in a voice choked with emotion: "Mr. Burns, I'm ready for my close-up."

This blog entry posted by Alan Kurtz.

Tags:

tres drole, mon vieux. but you have neglected my old friend Louis Gottschalk, the Caribbean Satch--a New World composer just as wacked out as Whiteman.

Brilliant piece, Mr. Kurtz- I'm still wiping my tears. Coleman may not have the first avant-guarist, but he still ushered in a new era by inventing the portable stove and gas lamp, thereby freeing millions of campers to enjoy the great outdoors in comfort.

Sorry to disillusion you, Dooflotch, but the Coleman Lantern was not invented by Ornette. It was actually his son Denardo who, while studying harmolodics by candlelight at age 10, began igniting kerosene, naphtha, gasoline and propane to produce intense bursts of white light. Following a near- disastrous series of house fires, Coleman the Younger finally figured how to control his nocturnal ignitions, and the rest, as they say, is history, making for happy campers the world over.

great article!