The Jazz.com Blog

March 23, 2009 · 1 comment

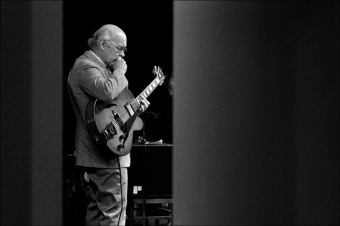

Jim Hall at the Library of Congress

Michael J. West, a regular contributor to jazz.com, has recently reported on performances by Kahil El’Zabar, Oliver Lake and Benny Golson in this space. Now he journeys to the Library of Congress to hear Jim Hall in concert.T.G.

In the Coolidge Auditorium, on the ground floor of the Library of Congress, Alan Lomax recorded Jelly Roll Morton’s reminiscences in 1938. Even seven decades later, it is surely daunting for jazz musicians to perform on that history-making spot. But if Jim Hall was intimidated last Friday night, he never let on; the legendary guitarist seemed comfortable as could be, and his trio-mates (bassist Steve LaSpina, drummer Joey Baron) exuded pure joy throughout their delightful and revelatory performance.

A sellout crowd applauded when the men entered, 79-year-old Hall walking with the aid of a cane but quick to joke about it (“I heard they were having auditions for House”). After introducing his musicians, Hall got right down to business, leading them into a beautiful, if unnamed, midtempo tune. It was an understated performance; Baron tapped at the kit with brushes, LaSpina more strident but still controlled with his buzzing bass vibrato. Hall was as subtle as always, but onstage he clarifies a stylistic aspect that on record is only apparent to other guitarists: His touch is not soft. In fact, he strums rather hard; the hush in his playing is because he keeps the volume and tone knobs on his electric guitar (a Jim Hall model Sadowsky archtop, naturally) at minimal levels. He fiddled with these throughout the set, but rarely with more than slight adjustment.

Hall didn’t need to call the second tune, “All the Things You Are.” But it was the chord changes that were instantly recognizable—Hall elongated and compressed the melody wherever it struck his fancy, recomposing Jerome Kern at will. His extraordinary harmonic ear was also on display in the odd but marvelous structures of his solo. The bassist offered a brilliant solo himself, concentrating in the instrument’s middle register, with Baron offering a waltz so delicate it was barely there.

Next, Hall asked a quiz question: What is the capital of Burkina Faso? The answer, Ouagadougou, was the title of the next tune, a Hall original. (“We’ve never been there,” he noted, “we just like the name.”) The 5/4 piece was unconventional by nearly every standard: It found Baron playing toms and snare with his fingertips while LaSpina offered a one-note bass line. Over top, Hall played jagged fragments of melody, with an aggressive and often speedy attack that evoked African pop.

The trio charged through another melodically oblong standard (“My Funny Valentine”) and a gentle bossa nova (“Beija-Flor”), then came a surprise: Hall announced a piece he’d written in Art Farmer’s band, “Big Blues,” which turned out to be a fast and genuinely urban blues. For the first time, Baron brandished sticks, knocking the rims of his bass and snare and taking an animated solo, after which he and LaSpina dropped out for a rowdy solo from Hall. With the song’s finish and the roar of approval from the audience, Hall smiled slyly and proclaimed, “You can have a lot of fun with these musical instruments!”

Subtlety returned, however, for two standards, “Body and Soul” and “Skylark.” The former was characterized by another melodic modification, and by LaSpina’s finest bass solo of the evening, this time fluctuating between mid- and high-register and filled with melodic triplet figures. It was “Skylark,” though, that was the more compelling. Hall fired off lightning-fast, flamenco-like runs; LaSpina offered an equally fleet-fingered solo, though it was more than a little similar to the one on “Body and Soul,” and Baron, despite sensitive brushwork, gave off an aura of delight with his enormous smile and contagious energy.

“Skylark” brought another tremendous ovation, with Hall smiling and apologizing that he didn’t rise to bow. “My heart’s in it,” he promised, “but my back isn’t.” The closing tune, he announced, would be another original blues, this one titled “Careful.” The name completely belied the mood of the piece, which was the closest Hall and company got to rock-and-roll. Hall’s attack was aggressive and ragged, with a choppy rhythm, and for this concluding number he finally turned on his tone knob—giving the guitar a brightness that seemed almost profane after the evening’s muted tone. LaSpina and Baron held down a hard-edged, even backbeat, the bassist with a firm low-end groove and the drummer in flux—smacking the snare like a bongo, grabbing the sticks for a workout on the snare and ride, and hammering out a rambunctious solo.

The excitement of the concert seems at odds with Hall’s obvious injury and walking stick, which underscored the guitarist’s advancing years. Yet his work onstage showed how much vitality is left in him, and how willing he still is to experiment with his repertoire and his very sound. If he was unfazed by playing on the same stage as Jelly Roll Morton, perhaps it was because he knew he’d do Jelly Roll proud.

This blog entry posted by Michael J. West

Tags:

I'm glad Jim was able to perform. I had tickets to see him on two occasions last year (in Colorado and in Oakland), and both gigs were cancelled because of his back surgery. I am going to be in Tokyo when he does his Japan tour in May and already have a ticket to one of his shows. There's no guitarist quite like Jim Hall.