The Jazz.com Blog

May 04, 2009 · 6 comments

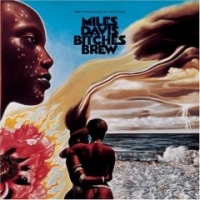

Reassessing Miles's Bitches Brew

Miles Davis's Bitches Brew is now almost forty years old. But this path-breaking album still generates controversy. Jared Pauley recently attended a symposium on this music, and finds that academic discourse and electric fusion don't always mix. T.G.

Miles Davis was always a rebel, continually pushing the envelope, both in his personal life and his musical life. From the 1950s to the time of his death in 1991, the trumpeter left a legacy that has challenged the notion of the jazz tradition more than that of any other artist.

Many people point to the start of his electric period as arguably the birth of fusion. I would have to agree 100% with that statement. Not just Davis, but the other musicians on Bitches Brew and In A Silent Way went on to champion the jazz-fusion movement in the 1970s. Its almost impossible to reach general agreement on the importance of Miles Davis electric period from a historical perspective, because some see it as the death of jazz (for a period of time) while others, including myself, would argue that the fusion movement was just a continuation of the jazz tradition. The only difference being that this new sound both incorporated the musical styles of the day and also the technological advances in musical equipment. I raise these points because I feel that it is useful to explore the historical implications of the Davis electric period.

Some of you reading this might be familiar with my article covering Columbia Universitys recent symposium on Jack Kerouac. On Monday April 6th, the university held another Center for Jazz Studies event, this time on the electric music of Miles Davis. The key speaker was Yale Universitys associate professor of ethnomusicology, Dr. Michael Veal. Veal presented a paper that explored the depths of the Lost Quintet. The Lost Quintet was the touring band of pianist Chick Corea, bassist Dave Holland, drummer Jack DeJohnette, saxophonist Wayne Shorter, and Miles Davis. This group toured from September 1969 to March 1970 on the heels of the Bitches Brew release, which came out in March. This touring band, in addition to guitarist John McLaughlin and pianists Joe Zawinul and Herbie Hancock recorded with Davis for his groundbreaking album Bitches Brew.

Dr. Michael Veal, a recognized leader in his field, has written books on the Jamaican musical diaspora as well as his upcoming book covering Miles Daviss electric period. His paper dealt with the rhythmic and tempo variations of the Lost Quintet and how the rhythm section would change behind Davis solos, frequently embracing a medium-swing tempo, which Davis preferred. Veal highlighted the different bootleg recordings of the song Agitation and how the second Miles Davis Quintet and the Lost Quintet interpreted this song. Veal coined the shift in tempo and rhythm behind Davis solos as the Skid. The Skid occurred on all of the examples he played for the thirty plus people in attendance.

I have listened to a wealth of Miles Davis in my short three decades on planet earth and I always noticed how the second Quintet would shift, almost unconsciously behind Miles, giving him the perfect, swinging backdrop. But Veal showed how the evolution of the second Quintet transcended to the Lost Quintet and eventually made its way to Bitches Brew. Veals hypothesis that the group aesthetic of reinterpretation was incorporated by the Bitches Brew band seems true. I rarely accept the opinions of scholars (or musicians) at face value but Veal was articulate and convincing in showing the connections and was also very clear pointing out the musical examples that tied the evolutions of the two groups directly to Bitches Brew.

Now for the part of the symposium that lost me within the first five minutes. Harald Kisiedu, a doctoral student in the program gave a response to Dr. Veals presentation dealing with technology and the way it affected jazz music. But, as with so many of the New Jazz Studies guys, I can never understand what the end result is or what their points are. Its amazes me to see the use of such big words yet with no clear cut point. Perhaps I just need to be conditioned more in the jargon of ethnomusicology but it was hard to understand why he even responded in the first place.

These Columbia symposiums are interesting but I get the feeling sometimes that the academic world is just writing for themselves. Hell, I know for a fact MOST of them are just writing for the inner circle. This defeats the purpose when we have so many brilliant minds exploring and dissecting the music but hardly any of them can equate it in laymans terms or for that matter present it in normal English. I suppose maybe with the influx of literary studies and cultural histories this was bound to happen.

I learned much more this time around than at the Jack Kerouac event I covered last month but thank goodness for Michael Veal. If he wasnt at this discussion I cant imagine where it might have headed. Overall, this was an interesting experience but not recommended for the average jazz head, because the nature of these events tends to alienate more than incorporate group discussions and individual input.

This blog entry posted by Jared Pauley

Tags:

I would have to disagree wholeheartedly that the ethnomusicology community is writing only for themselves. The use of "jargon" can become overwhelming, and certainly can also be self-serving, but at the heart of the endeavor is the attempt to articulately explain various musical phenomena. More often than not, words frequently used to describe music are worn out, weighed down by decades of use, often casual or careless use that stretches their definitions to the point of rupture. For instance, when you argue that Miles' electric period was just a continuation of the "jazz tradition" I wonder: What tradition? Whose tradition? Tradition is a dried up word. Wynton Marsalis would argue that Miles violated the jazz tradition, you argue that he continued it; if neither of you can define the tradition it's an empty argument altogether. Really, when it works academic "jargon" is about fusion too; one attempts to use existing language elements to come up with a new way of articulating something she feels is important. Many words or phrases we now take for granted--soundscape, "imagined community," versioning--come directly from this process. Perhaps Kisiedu's paper was a miss (I didn't see it), but to decide that "MOST" academic thinkers are concerned only with the "inner circle" is rather shortsided. If someone cares enough to live off a stipend for 4 years while he researches music and conducts countless interviews of musicians, he probably cares quite a lot about the music and has serious intentions of doing something positive for it and its practitioners.

Nice points Bill. I don't disagree with what you are saying. I myself come from the world of academics but the point is that most musicians when describing music, DON'T talk like musicologists. In fact, I have lived off of loans and stipends for the last two years, only to learn that most of the academic community does write exclusively for itself. I would like to see an average music lover with above average intelligence try and read the work of George Lewis or Anthony Braxton and come away enlightened. If they are able to maneuver through the words and vocabulary, perhaps, they would come away with a new view point or a new sense of critical analysis, but more often than not, most people could not sift through enough ethnomusicology to reach a conclusion, because of the vocabulary.

The problem began when art and music criticism felt a need to catch up to the convoluted verbosity of literary analysis. Hey, we need to be taken seriously too! (Right?) It's all about "legitimacy", even as most Americans believe that jazz is Boney James and Rick Braun, or at best- Wynton Marsalis and his museum jazz. This is where the real work needs to be done and yet academics would rather sit around debating the meaning of Bitches Brew. Call me anti-intellectual or "reductionist", but all one really needs to know about Bitches Brew is that Miles did what the f*ck he wanted to. Was he immune to cultural forces or the social climate at the time? No, of course not- but he also didn't sit around pondering what he should do from some theoretical standpoint. If he, or Coltrane, or many of the other trailblazers overthought things to the extent that academics are want to do, nothing would have ever gotten done. George Lewis and Anthony Braxton are a different story. They are ripe for academic analysis because their music is often based from theoretical constructs, which is also why their music will never have the potency or broader relevance that Miles' did. All of this is just to say that when you try to analyze the meaning and raison d'etre of musicians like Miles Davis or Ornette Coleman, et al, you can't possibly not do an injustice to the main reason for that music's existence--- the individual's creative impulses. And no, I'm not advocating for the "great man theory" of jazz. I am saying however that with every "movement", the main reason for that movement taking place was the initiative of a few key creative minds coming together.

I think you both make good points but I would have to disagree with Gerard on the notion that "the main reason for that movement taking place was the initiative of a few key creative minds coming together." I think what great ethnomusicology tries to prove, and often does, is that it's actually the opposite. The truth is that jazz existed originally within communities essentially as a form of popular music and was nurtured by a huge swath of humanity that includes those people we celebrate over and over as well as thousands of others who performed, owned clubs and labels, or even just went out and danced and socialized to it. The great success of Paul Berliner's and Ingrid Monson's works (to name a few) is that they've situated the music within these communities and demonstrated how these final products we love so much were spawned over the course of lifetimes in communities. Is it really a bad thing that Ingrid Monson chose to discuss "Signifyin(g)" within jazz? I would say definitely not because it validates a musical process that is at the heart of jazz and also recognizes that jazz owes a great debt to African American communities and cultural practices. Moreover, I find her adaptation of the literary criticism term "intertextuality," which she refigures as "intermusicality," totally useful and meaningful as a way to think about the ways in which improvisers step up to the plate nightly. Ok, it's an academic term but if most of the world was willing to take the two seconds to Google it I think the world would be a better place. "Layman's terms" are the stuff of Rove campaigns; to me the idea that we shouldn't stretch our vocabularies, especially in an age when we correspond mostly with keyboards, is silly. (Again though, I recognize that this can go too far, especially in grad student papers). Either way, it's nice having this conversation, thanks.

Any time there is a specialized field of study there will be specialized jargon. That's true for academics as well as the people who fix our cars. Academic study can provide useful information if we're willing to understand the concepts and vocabulary. However, with music (such as Miles Davis' recordings) the main point is to enjoy...

To be clear I'm not opposed to specialized terms in principle. I just see where the more one tries to contextualize and rationalize why some music or arts movement came into being, the more the individual artist is left in the dust as some kind of mere vessel of social and cultural forces. Maybe this sounds Ayn Rand-ish, I don't know. As per Bill's point, I would definitely concede that different movements occur organically and within the context of communities of collaborators, though I would offer something of a counterpoint in that....if you had no Charlie Parker, there most likely wouldn't have been a Sonny Stitt, a Jackie McLean, Lou Donaldson, and so forth. I think without these particular visionary artists, the styles or movements they were a part of would not have had nearly the same potency. They set out roadmaps for artists of lesser gifts but similar aesthetic inclinations to work from.