The Jazz.com Blog

June 05, 2009 · 13 comments

How I Learned I Was a Jazz Fan

People sometimes ask me how I became interested in jazz. In my case, there was an electrifying moment of discovery at a jazz club—literally a few seconds of listening that changed my life—but I am savvy enough to realize that there must have been a series of events leading up to that experience.

What brought me to a jazz club in the first place? What spurred me to seek out this music that was under the radar screens of mainstream culture, and not a part of the life of my friends and classmates?

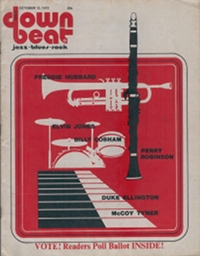

A chance event at the local public library (see photo) may have been the turning-point. I stumbled by luck on a pile of issues of Downbeat magazine, and began paging through them. I puzzled over the names in the "Readers Poll" (almost all of them unfamiliar to me); I read the reviews and interviews; I imbibed the compact wisdom of the "blindfold tests."

City of Hawthorne Public Library at the

Time of the Blogger's Childhood

The concept of jazz appealed to me before I knew much about the music. I was a devoted—indeed, almost obsessed—piano student back then, and spent hours every day at the keyboard. Yet I felt a certain hollowness in my musical tastes. I found rock music viscerally exciting, but was turned off by its lack of complexity. Classical music, in contrast, fascinated me because of its intricacy—it offered intellectual sustenance—but lacked immediacy and energy. I dimly realized that there was this other type of music, called jazz, that promised a combination of both. This suspicion fueled my devouring of the public library's stack of jazz magazines.

These magazines spurred me to the key next steps. I began checking out the jazz records in the library's collection—probably forty or so LPs—and every jazz book on its shelves. Finally the grand moment arrived when I decided to cross the great divide . . . and go to a jazz club. I enlisted a friend to join me for moral support—and set a date to see one of the bands whose name I had encountered in Downbeat.

Many of these clubs refused to let minors on to their premises. I remember Howard Rumsey was booking name bands at his "Concerts by the Sea" club in Redondo Beach, but he vigilantly guarded the door against people just like me. A teenager would have had an easier time buying an automatic weapon from a passerby than getting inside his club. I would hang out by the front entrance and imagine what wonderful things might be happening inside. (One night, escorting a woman to the door, Rumsey could be heard exclaiming: "Listen lady, I've been in this business for decades, and I know drunk when I see it.") To this day, I have no idea what the inside of that club looked like.

I was fortunate that other clubs had more tolerant policies. In particular, the Lighthouse in nearby Hermosa Beach (Mr. Rumsey's old home base, where he had led the house band for many years), was still promoting jazz back then, and they allowed minors to attend.

"Minors are always cool at the Lighthouse," was a recurring tagline on their radio ads. (Younger fans may find this hard to believe, but there were once commercial jazz radio stations—not just non-profit and college stations—and clubs advertised regularly on the airwaves.) And the way the ad copy was delivered, in a deep-sexy-Barry-White kind of voice, made me realize what a great privilege it was to be a minor and gain entrance to this citadel of jazz. I decided I would go to the Lighthouse, and—in an attempt to live up to their radio slogan—try to be as cool as possible.

I remember that first evening vividly even now. I stayed for all three sets. But the key moment happened within the first fifteen seconds of music-making. When I heard the rhythm section leap out of the starting gate with such fire, yet also such precision . . . I was transformed. I would love to see a video clip of my facial expression during the first moments of the first song of the first set. I knew at that instant, that I had discovered something that had changed me. It would be ridiculous to claim that I could tell then that I would make jazz records and write jazz books and spend much of my life immersed in this music. Yet it would also be wrong to deny that I had some hunch, even then, that my life would go down a different path because of my decision to walk inside a jazz club that evening.

To this day, one of my core beliefs is that music has a force of enchantment. Music is, in a very real sense, magical and transformative. Those who are familiar with my books Healing Songs and Work Songs know that I often speak of music as a "change agent." This is not an abstract idea in my head, but a conviction based on personal experience.

One of my gripes about so many jazz educational efforts (and the Ken Burns documentary in particular) is that they don't nurture this sense of enchantment. When you treat jazz as a "historical sociological phenomenon," don't be surprised when people don't go to the jazz clubs. No one goes to a jazz club for a sociology lesson—or if they do, they only go once.

But the magic of the music is very real. Even today, in the degraded state of the industry, the magic exists, and is only slightly tarnished by all the efforts to treat music as just another consumer product. "They lost confidence in the product," was the astute recent diagnosis of the record business's collapse by a insider. Ah, but the problem started when they began looking it as a "product" in the first place. Mr. Music Mogul, are you selling a physical consumer good, a compact disk manufactured out of polycarbonate, or are you dealing in transformative metaphysical experiences disseminated in sounds and feelings?

As Geoff Dyer has smartly pointed out, painters and gallery owners talk about the "art world," while record label execs call their field the "music business." Jazz world or jazz business, you choose? Record companies went down the business path long ago, and at some point most of them forgot about the magic.

All jazz fans have a "gateway experience" of the sort I described—a pivotal moment when they first felt the magic of the music. The jazz world needs to spend less time arguing with itself and put more thought and energy into expanding these gateways and building new ones. For some fans, the gateway to jazz is a song heard on the radio. But what happens when the radio stations stop playing jazz? For others, it is moment in school. But what happens when the schools eliminate their music programs? For still others, it is an experience at a festival. But what happens when the festivals shut down, or fill their stages with non-jazz acts?

For me, the gateway to jazz was through the pages of a magazine. When I hear that one of the leading jazz magazines may disappear—as is the prevailing rumor this week—I worry about how many gateways will still be standing when the next generation of potential fans arrive on the scene. I am sure that there are millions of people who have the same hunger for something magical in music that brought me to jazz, a desire for soundscapes that can be both intellectually satisfying and emotionally invigorating. Jazz could be part of their enchantment, as it was a key part of mine. But if all the gateways are closed, they may never realize it.

This blog entry posted by Ted Gioia

Tags:

Excellent work, Ted. I had a very similar experience in the early 1960s. I grew up in a remote, rural part of Mississippi. I had gravitated to the saxophone early on--no idea why--and was playing it in the school band, but really didn't know what the instrument, at least in my hands, was FOR. In a bookstore I chanced across a copy of DownBeat, and there on the cover was a guy with a sax. I picked it up, glanced through it, and knew I had to buy it. What I found there changed everything. Hang in there DownBeat. We need you. Thanks Ted.

You don't know me, Mr. Gioia, but I have been a fan of yours for a long long time. Thank you for this terrific piece. I'm a pal of your bro, Dana, and Terry's an old friend too. Turns out you and Dana and I were all born in the same hospital in Hawthorne (thanks for the cool photo of the library). My own experience of discovering the genuine transformational magic of jazz came about when I stumbled across good ol' KBCA one night when I was in high school -- I went to Edison down in Huntington Beach -- and heard a Roger Kelloway cut. I'd played in jazz band in school -- I play sax (as Terry knows) -- but that night I was hooked on the core moment of discovery and surprise and beauty and joy. From then on it it was KBCA and Chuck Niles and Jim Gosa. The best date my then-girlfriend and I ever went on was to see Richie Cole at Carmelo's out in Sherman Oaks. We've been married now 29 years. That's the power of jazz. I look forward to meeting you one day -- and keep up the good work. I hope the rumors about Downbeat are just that -- Bret Lott

Thanks for your comments. I am especially happy to hear Bret sing the praises of Chuck Niles, who inspired me too (and lots of other jazz fans, I am sure). By the way, I should note that, although I talk about Downbeat in my article, the magazine rumored to be in trouble is Jazz Times.

Ted, I know your forthcoming book The Birth (and Death) of the Cool addresses the death of irony in contemporary culture, but I think even you must admit that irony lives when the proprietor of a jazz web site frets over the rumored demise of a print periodical. Whenever I see a discussion on C-SPAN about the woes of print media, the very first culprit that every expert indicts is the Internet, which is blamed for universally decimating the readership base.

I understand your concern that "if all the gateways are closed," jazz will become inaccessible to potential fans. But with apologies to Chicken Little, the sky is not falling. Gateways come and go. When a superhighway replaces an old two-lane blacktop, the businesses along the less traveled road suffer and die. Even so, people still get where they want to goin this case, faster and more conveniently. Portals such as jazz.com are the wave of the present. JazzTimes is a thing of the past, whether it ceases publication now or later. Rest assured, 35 years from today some blogger will wax nostalgic about how he or she at age 15 stumbled upon jazz.com in 2009 and how the experience led to a transformative first encounter with this enchanting music.

As to your larger point, I remain unconvinced that selling jazz as a product or preserving it as a museum piece are necessarily bad things. It's easy to knock Ken Burns as both a commodifier and curator. Yet we'll never know how many people have, since its PBS premiere in 2001, come to jazz by way of Burns's epic 10-part documentary, whether as originally telecast, repeatedly rerun or presented on DVD, or through the two dozen compilation CDs (singles and reasonably priced box sets) or handsome companion book by Burns and Geoffrey C. Ward. Even if Burns's Jazz did not enchant millions, I'll bet the number was at least as significant as the cumulative circulation of JazzTimes.

Years ago, CBS-TV presented an adaptation of Much Ado About Nothing prefaced by an announcement: "Through tonight's single broadcast, more people will view this play than have seen all its theatrical presentations combined since its first production in 1612." For me as an aspiring young writer, having never been privy to Shakespeare performed on stage, watching this man's mind at work was as enchanting and transformative as your musical illumination at the Lighthouse. There's something to be said for merchandizing museum pieces.

Alan, this is more than an issue of print media being replaced by web media. The jazz audience is disappearing, and at a rapid pace. Since jazz.com was launched (in December 2007), I have watched the JVC Jazz Festival disappear, other jazz festivals drop jazz musicians from their lineups, IAJE declare bankruptcy, Concord delete many items in its catalog, jazz clubs shut their doors, radio stations eliminate jazz from their playlist, and now jazz magazines pulling the plug.

Anyone in jazz who thinks that they don't need to be worried about this - because they write for the web or for whatever other reason - is in deep denial. I have said this before, and I will repeat it: the music is in a state of crisis. And it is a crisis unfolding at a grassroots level because insufficient attention has been given to audience development for far too long. I am dismayed by the complacency in the ranks, but even more by the smug sense that someone else's misfortune in the jazz world is not my problem. JALC or Blue Note or the Village Vanguard could close shop, and some would even gloat or celebrate.

Too many members of the jazz community fail to understand how interconnected the jazz economy is. As Howard Mandel has shown, the end of the JVC Festival may have been the reason why Jazz Times is on the ropes. If you think that this won't spread elsewhere, you don't understand the fragile nature of most jazz operations and how much they depend on other jazz institutions for their own survival.

Ted, with respect, I don't think my attitude can fairly be called complacency. In The Grapes of Wrath, Ma Joad contrasts the way men and women react to change. "Man, he lives in jerks," she tells Pa. "Baby born an' a man dies, an' that's a jerk; gets a farm an' loses his farm, an' that's a jerk. Woman, it's all one flow, like a stream; little eddies, little waterfalls, but the river, it goes right on. We ain't gonna die out. People is goin' onchangin' a little, maybe, but goin' right on."

This is not complacency. It simply recognizes the inevitability of change. "The jazz audience is disappearing," you write. Cataloging calamities that have beset jazz since December 2007, you conclude that "the music is in a state of crisis." Hello! Earth to Mr. Gioia! The entire planet is in a state of crisis. Why should jazz be immune?

Regrettably, instead of evaluating present-day jazz within its macroeconomic context, you promote a conspiracy theory. Last month, in your blog "Talking to Myself About the State of Jazz Music," you referred to an unnamed "influential contingent in the jazz world that would like to keep the art form small and untainted by the need to please an audience." In today's blog, you blame that familiar whipping boy Ken Burns and "record label execs," including someone you identify only as Mr. Music Mogul. Am I the only one who remembers Senator Joseph McCarthy in 1950 waving his list of "known Communists" infesting the U.S. State Department, whose names he refused to reveal and whose number kept fluctuating depending on his blood alcohol content?

Okay, admittedly, you're not that paranoid. But honestly, what can ordinary people like me and Ma Joad do, Ted? Are we supposed to email our congresswoman? Boycott Ken Burns? Please, give us something concrete to go on.

Alan, you don't think there are people in the jazz world who want to keep it small and untainted by a large general audience? I don't need to name names. Just look at the comments to the "State of Jazz" blog article you mention. You will see it all spelled out there. Check out the article Mr. Khan refers to in his comments. Check out any posting on Wynton Marsalis on any jazz forum. Pay a visit to (your favorite web site) Bagatellen. Do a Google search on "Jazz at Lincoln Center," and find out what is being posted on the web about it. Do a search on "IAJE bankruptcy." Go check out what jazz people said about Norah Jones when she won a Grammy. Go check out what jazz people said when Herbie Hancock got a Grammy for his Joni Mitchell CD. Go back and see what they said when Brubeck got on the cover of Time magazine. Read what they wrote about Keith Jarrett when his Koln Concert sold a zillion copies, and compare it to what they wrote when his recordings sold in tiny quantities. Go check out what they said when the fusion stars expanded the jazz audience in the 1970s. Check out what they said about West Coast jazz when it developed a crossover audience in the 1950s. Earth to Alan Kurtz: Haven't you noticed that these successes were not universally celebrated in the jazz world?

And you're missing the action if you think that the decline in the jazz audience is simply a result of the current economic crisis. This decline has been a long term secular trend that is merely accelerating since the financial collapse. Do you think that IAJE and Jazz Times will come back when the housing market has an uptick? Unlikely. Alan, the very comments you make are indicative of the state of denial that is pervasive these days. You look at the collapse around us, and describe it as the "inevitability of change"?

I regret to report that I was unable to complete all 11 items on the preceding "To Do" list that you thoughtfully prepared for me. (1) Marty Khan's "Hello I Must Be Going," published in 2005 on allaboutjazz.com, is an unreadable rant; I can't believe it has influenced anyone, since no one besides Marty could decipher it. (2) You said "any jazz forum" re Wynton Marsalis, so naturally I went to jazz.com's Forum, where I found 14 posts, all of which are entirely respectful towards Marsalis and JALC. (3) Bagatellen is, of course, is a private joke between you and me; LOL. (4) A Google search for "Jazz at Lincoln Center" yields 1,280,000 hits. Could you possibly suggest a way to narrow this down? (5) thru (11) are impracticable because in each case you instruct me to check out what "jazz people" or "they" said. Which "jazz people"? Who "they"? (I know what Duke Ellington said about Dave Brubeck getting on the cover of Time magazine; as always, Duke was quite gracious. But otherwise I haven't a clue.)

The problem with all this, Ted, even if I could realistically complete the deliberately undoable task you've assigned, is that finding out what "they" said at any given point about a particular artist or event in no way establishes cause and effect. If "they" bad mouthed Wynton Marsalis, Norah Jones, Herbie Hancock, Dave Brubeck, Keith Jarrett, fusion stars, or the icons of West Coast jazz, it doesn't seem to have hurt the careers of those named, all of whom made a great deal of money and reached a worldwide audience. Perhaps no one back then gave a damn what "they" said, just as nobody cares now.

Alan, first you complain that I am not being specific enough when I claim that there are people who would like keep the jazz world "small and pure." Then you complain when I give you a long list of places to go for confirmation. You are truly a curmudgeon.

I was hoping that there would be some commentary in response to your posting, but I didn't expect an argument between Alan and Ted! Ted, you did an excellent job of laying out your own transformational experience with jazz, and I enjoyed reading it because it got me thinking about my own experiences discovering jazz in the late 1990s (feeling old now?) My avenue for learning about jazz was through my school, specifically my middle school band director and my trombone teacher. Their mentorship spurred my interest in jazz, suggested hip CDs to buy, told me about the best record store in Downtown Portland, and introduced me to their other students who were going down the same path. Of course, I had some similarly transformational experiences listening to jazz, but I also had powerful experiences hearing a Maceo Parker concert (self-proclaimed only 2% jazz) as well as more funk-oriented groups like Galactic, certainly on the fringes of what you might consider jazz. There's a big difference between you getting your introduction to jazz through reading and me getting mine through a musical mentor. Because more and more young people are being exposed to jazz in school, the paradigm for those early transformational experiences is shifting. Alan is right in that change is inevitable in the delivery of content, and JazzTimes will be the latest casualty in that development. We're still figuring out how to make this work as the domestic jazz audience seems to be shrinking. Jazz is, I believe, becoming a little bit less of a collector's music and a little bit more of a music of shared experience by amateur musicians. But I think the developments in web-oriented content development will highlight the fact that the audience for jazz is actually growing, only it is dispersed more widely across the entire planet. Not just in Europe, either: jazz developments in Africa, East Asia and Latin America are happening all the time. As we begin to better understand how to communicate with one another and to utilize the current generation of jazz enthusiasts to best effect, it will be apparent that jazz is not facing extinction. I agree with your criticism of "Ken Burns types" who want to mummify jazz and put it in a museum. That's not where it belongs. But I disagree with your pessimism about the state of the jazz audience globally. Part of the beauty of jazz is that it's flexible enough to accommodate everyone's varying transformational experiences with the music.

Alex, thanks for bringing us back down to earth. Meanwhile, Alan and I have declared a truce. However, I suspect that he is still continuing with his secret weapon development program.

As long as he doesn't kick out the weapons inspectors or conduct any illegal underground tests, I think we'll be alright.

Comment 13? By a small coincidence, I posted my own how-I-came-to-Jazz piece 10 days ago at www.mrebks.blogspot.com -- Since it too involves Brubeck and (peripherally) Ted Gioia, someone reading this air-war exchange between TG and AK-47 might also be amused by my personal take. (Flu shots advised...)