The Jazz.com Blog

July 03, 2009 · 1 comment

The Detectives of Jazz

Will Friedwald continues his series on jazz discographers below. Your software spellchecker may not like "discographers" and try to substitute "disco photographers" in their place. But jazz fans are deeply indebted to these indefatigable researchers who determine who played what, when, where and with who. Think of them as slightly more swingin' versions of Sherlock Holmes, with a cool stereo system instead of a pipe and deerstalker. Click here for the first and second installments of this article. T.G.

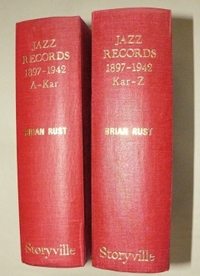

Brian Rust's Jazz Records is remarkable for its subjectivity; collectors still delight in finding a hot side by a dance band that the author doesnt list. (One area he largely overlooks is country music: there are plenty of sides by Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys with genuine jazz content that deserve to be listed. Another is bands outside of America and England and the Swiss New Hot Players. Tom Lord has made a significant improvement in his online Jazz Discography, for instance, by including all the known sessions by the pioneering Dutch hot band The Ramblers - not just those dates where Coleman Hawkins guest stars).

Published in 1975, The American Dance Band Discography is notable at once for its tight focus, and, at the same time, the sheer scope of its ambition. The ABDB strictly focuses on white dance bands, meaning no singers (except doing band vocal refrains), no small groups, no Afro-American bands (theyre all covered in detail in JR). (He also left out Benny Goodman, explaining that they were covered in detail in two book-length discographies then available from Arlington House.) And even so, its enormous and its very enormity helps put the entire era in perspective, showing that pure jazz represented just a small portion of the big picture of what people listened to even in the jazz age and the swing era.

The ABDB is where Mr. Rust undertook the impossible task of documenting everything recorded not only by working bands, like Whiteman and Isham Jones, who played theaters and ballrooms all over the country, but even house bandleaders, like Fred Rich and Victor Young. As opposed to the peripatetic road bands of the period, their sole job it was to stay in one place - the studios - for 12 hours a day and grind out as many discs as it was possible, sending out only occasionally for scotch and sandwiches.

The sheer quantity of all of their output seems incredulous to later generations: both immediately before and after the depths of the depression, the major bands of the era were releasing hundreds of sides a year. Documenting all the dates, song titles, and piecing together all the musicians, and identifying all the band vocalists (even if it seems like the same three guys sing on every record) is the job of a lifetime. As Mr. Rust would say, the effort was not so much exhaustive as exhausting.

Hardcore collectors, like John Leifert and the late Jeff Healey, have added in so many corrections that there are more pencil marks on the pages of their copies than there is printing. Yet because the ABDB is the only one of Mr. Rusts seminal works that has never been revised, I can name a few younger aficionados, who have been born since 1975, who are relying on info that hasnt been updated for their whole lives. This is due to change this year (2009), when, after nearly 35 years, Mainspring Press (a specialist in this literature, who published the most recent 6tthedition of Jazz Records) will release a long-awaited new edition of the ABDB.

The new American Dance Band Discography is due to the efforts of another Brit, one Richard Johnson, who has spent several decades overhauling the 1975 work, adding personnel, issue numbers, new vocalists IDs, and adding in more info regarding non-commercial sessions (for transcriptions and film soundtracks, etc). He tells me (in an old-fashioned handwritten airmail letter no less) that the new edition will come in at 5,000 pages, which is two-and-a-half times the length of the original. Among other additions, there will at last be a song index (hallelujah!) and the work will also be available in electronic form on CDROM (double hallelujah!). (I hope to review and discuss the new edition in this spot when its released at the end of this year.)

I must confess that in the last few years, ever since Tom Lord incorporated (and expanded upon) most of the information from Rusts Jazz Records into the various electronic editions of The Jazz Discography (especially the current and invaluable online version), I have tended to spend less time pouring through my old-school hardcover copies of Rusts Jazz Records. Contrastingly, all of our copies of the 1975 ABDB are literally falling apart from overuse; these are volumes that have spent most of their existence open on our desks rather than gathering dust on our shelves.

Small wonder Roger wanted to gather us all up to visit Mr. Rust in his home in TK, so we could genuflect at his feet. Roger didnt want Rust to leave this world behind before we could tell him how essential his work is to us. Ironically, Roger died way before Brian, who is very much with us at age 87. Even more than Brian Rust himself, his legacy of research will be around forever, and future generations of scholars will continue to base their lives on his teachings.

This blog entry posted by Will Friedwald

Tags:

It's too bad American Dance Band Discography has never been revised till now, but in a way it ought to be obvious.

First, there's the immensity of the genre - genres, really: swing, several kinds of sweet (society, hotel, three tenor, mickey mouse...), a few high-flying latin outfits, and the endless middle-of-the-road, sometimes so bland, sometimes so surprisingly pleasant and highly musical.

There's also a sad fact to contend with: 95% or better of the ABDB genre(s) is of no relevance to anyone but the few thousand, if that many, of us active, non-academic collectors. Critically, this music is a dead letter - good as it can be, there's no reason for it to be that good. It has no pedigree: bands borrowed from jazz, the theater, the movies and Tin Pan Alley, but the band business wasn't part of those institutions, so it can't be studied as their products are today. The main reason for the bands being there at all - ballroom dancing as a mass pleasure - is irretrievably gone, along with almost all the audience, adding social irrelevancy to musical.

This was always ephemeral music, until it became extinct. Now a few of us understand how rich some of it is, and how high the quality often was for a product of yard-goods commercialism. I like to compare it to men's ready-to-wear clothing, another vintage artifact I enjoy. Compared with what's for sale today, the old stuff is much better crafted, uses better materials, and often, has head and shoulders more style.

Still, this is pop culture from an orphan sector - the dead world of the dance hall - and most of it is from an era when there wasn't supposed to be any pop culture: pre-consumer culture, pre-affluence, and by now, pre-living-memory. And that, it seems, is that.

I wish it were different. This music is a valuable part of the cultural legacy of the 20th century, with such subtlety and diversity, but there seems to be no way to make even the rarefied world of academia and criticalia aware of what it really is - at least in the context of American high-or-low culture. (It says a lot that it took a Briton to essay both ABDB projects.) If you call art a direction away from commerce, what is neither artistic nor, any longer, commercial is junk. But much of American dance band music is too good to be junk.