The Jazz.com Blog

August 03, 2009 · 1 comment

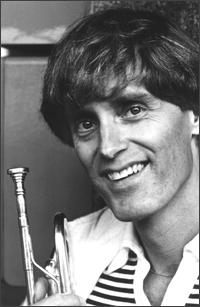

Remembering Don Ellis (Part 2)

Jeff Sultanof continues his look at the innovative bandleader Don Ellis in the second and final installment of his two-part article below. (For part one of this article, click here.) T.G.

Ellis showed that he was a born showman and promoterhe asked his audiences to begin a letter-writing campaign to convince the producers of the Monterey Jazz Festival to book the band. Elliss September 18, 1966 appearance at the festival sent shock waves through the show business world. That performance was released on a Pacific Jazz album, and another live album from two other live performances from 1966 and 1967 was even better. Ellis book included his own compositions, his settings of standards such as Angel Eyes and Freedom Jazz Dance, and contributions from Jaki Byard and Hank Levy. Eventually band members such as Sam Falzone and Fred Selden would write important music to add to the repertoire.

Ellis signed with Columbia Records in 1967, quite a statement when one considers that Columbia was dumping jazz artists and long-time performers from their roster and signing Simon and Garfunkel, the Byrds, and Big Brother and the Holding Company (with Janis Joplin). The Ellis band recorded its first studio-recorded album, and even with John Hammond as producer, Electric Bath is somewhat of a disappointment, as it fails to recreate the excitement of a live performance. And that was part of the bands legend. Ellis knew how to whip up his audience into a frenzy via exciting music and soloists, then change mood with something more meditative. Listeners (I was one of them) walked out of an Ellis concert exhausted yet hyper at the same time.

The Ellis band is proof that if you build it, they will come. Like Stan Kenton, to whom he was often compared, he was a striking figure who knew how to sell his product, and his often flamboyant presentation drew all sorts of listeners. He appealed to many older big band fans as well as young jazz and rock players. He shared the stage with such diverse groups as the Modern Jazz Quartet and the Mothers Of Invention, and played rock clubs, where the audiences danced to music in 7, 9, 13 and even 33. Ellis incorporated electronic devices such as the echoplex and tone splitters to his own trumpet playing before Miles Davis tried them. Electronic keyboards such as the Clavinet and the Fender Rhodes were heard by many listeners for the first time. Adventurous high school and college big bands played some of his music, spreading the message even further.

Shock Treatment, Elliss next album, was screwed up badly by the label, I suspect by producer Hammond. Ellis turned in the master and was shocked to find that it had been tampered with upon release. The album turns up in three different versions, but the CD release on Koch Jazz is definitive thanks to Ellis historian Nick Di Scala.

Columbia was having a great deal of success with Blood, Sweat and Tears, and label head Clive Davis suggested that BS&T producer Al Kooper work on Ellis next album. This release was split between live and concert performances. The band now included legendary saxophonist John Klemmer, who sounded like John Coltrane on acid (Klemmers solos with Ellis band at Fillmore West can be heard on a CD reissue of the double LP). Ellis must have been selling records in nice numbers, as Columbia was known as a label that dumped artists and bought out their contracts if their sales were bad.

One of the most important musical contributors to the Ellis band was ex-Kenton saxophonist, Hank Levy. In 1970, Stan Kenton asked Levy to compose material for his band, which was entering a new level of success in concerts and clinics at colleges. After the first rehearsal, the Kenton musicians were so dispirited at being unable to play Levys music that they wanted to throw both Kenton and Levy off the roof of their hotel. They continued to work on the music, and could eventually play it quite well. Levy wrote for both Ellis and Kenton for a time.

In 1971 Ellis put together a new band with a string quartet, amplifying them with attachments made by Barcus-Berry, another innovation. The bands performances at this time were happenings comparable to performances by the Grateful Dead. I believe that this was Ellis musical high point, and other writers such as Bill Kirchner have agreed. This band blended symphonic music, rock, multi-ethnic sources, jazz and Brazilian music into a compatible, beautiful mix. Ellis worked on his drumming so that he could join in three-way drum solos with the other percussionists.

If you buy one Don Ellis CD, Tears of Joy, (another live album originally issued as 2 LPs) is the one to get. Ellis welcomed a new pianist/composer all the way from Bulgaria, Milcho Leviev, who had sent him a folk song that Ellis adapted as Bulgarian Bulge. Certainly one of the most difficult pieces the Ellis band ever played, Levievs improvisations held audiences of all ages and backgrounds spellbound. Strawberry Soup, another Ellis composition was so intricate that it has been the studied in Masters and Doctoral dissertations.

Elliss star continued to ascend. He was asked to write the score to William Friedkins The French Connection, winning a Grammy award for the theme. He also wrote music for the sequel, The French Connection II, but it was clear that the man and his music were too unconventional for Hollywood. He insisted on using his own orchestra to record the soundtrack, which did not endear him to contractors, and further scoring opportunities just were not forthcoming. No longer with Columbia, Ellis made two albums with the German label MPS, one with the band, one with a string orchestra.

In 1972, Ellis was diagnosed with cardiomyopathy, and had a near-fatal heart attack in 1975. After recovering, Ellis went right back to leading a band, and signed a new contract with Atlantic Records. The first album was a disappointment as it was branded as too commercial, but the second was another live album that was very impressive. Ellis did not have the time to savor his comeback; he died on December 17, 1978. Educational jazz organizations such as the IAJE totally forgot him soon after he died (although this was hardly unique; they forgot Woody Herman and Stan Kenton as well). His music stopped being played. It was time to move to the next new thing.

While there is a lot of information and some good interviews (including those by Ellis himself) in John Visuzzis documentary on the artist, we do not really grasp why all of this was so important. The context in which Ellis created his music is totally missingviewers may not understand that interest in big bands were at an all time low in 1966; that a new one would be formed in the United States and tour Europe was unheard of then, let alone share stages with the top rock acts of the era. To this day, no one but Ellis has been able to fuse so many disparate musical elements and a big band instrumentation and make a unique musical statement understood by so many from all age groups, and actually make money doing it.

There also needed to be a lot more concert footage in the documentary; the music presented is good and much of it is in fine shape visually and sonically, but there are not enough examples showing the diversity of Dons music. Luckily there is a stunning version of Bulgarian Bulge, which includes one of Elliss wonderful spoken introductions.

The documentary is also much too short. Perhaps this was due to budgetary constraints, but if you want to tell the world of this visionary man and his amazing band, it simply cant be done in a little over an hour. And then there are the things that really disturbed me: Hank Levy, who played a great part in Elliss ensemble and later Stan Kentons is simply identified as legendary composer. Levy had quite a story as well, and to have him barely mentioned here was not a good decision (ironically, there is a documentary on Levy on DVD. He was a fine musician and excellent teacher). Interviewee Gunther Schuller compliments Ellis while reminding us of his own importance, as if he really needed to do that.

And yet I ask you to purchase this DVD, or at least rent it, because the disc has over 150 minutes of extras (longer than the movie!?!?). More interviews (why werent more of these incorporated?), another Ellis performance, and rehearsal and concert footage of an Ellis band reunion in 2005 directed by Milcho Leviev may be found. (I must confess that even though this concert was well-meaning, it takes more than a couple of rehearsals, even with Ellis alumni, to get this music to really sound the way it could.)

Thankfully the original albums are available on CD. The Ellis book is slowly being made available in critical editionsas someone who prepares this type of work myself, I find this is wonderful news to hear. Elliss music can be difficult, but with a sympathetic and knowledgeable bandleader/educator and excellent musicians who like to be challenged, the results are magical. Indian Lady should be in every college big band book; even the college band I led for two years was able to play it, and the musicians told me they wanted to play more of the same, as hard as it was. It is still a great concert closer.

Ellis is finally getting his due for the many contributions he made, and while the documentary qualifies as a nice try, it is good to have for all the extras and a memory of the man. And if you havent heard the Ellis ensemble, hopefully these words will inspire you to explore his many musical worlds.

This blog entry posted by Jeff Sultanof

Tags:

Thanks for your insightful commentary on Don Ellis.

And even more so your thoughts about Hank Levy. I was a student of Hank's, a friend of Glenn Stuart and acquainted with Don, although he died only a year after I got to LA after university. Hank has been grossly underrated, and I've been on a "quest" the last few years to get his music in the books of several big bands including the Chicago Metropolitan and two bands in Japan.

Hank in point of fact had a better "handle" on the time signature work, and Don was learning much from the work Hank was doing.

Hank was especially shattered by Don's passing, even more than with Stan. He realized his future was "tied up" with Don's ability to play what he was writing.

I was close friends with Hank until his death in 2001. I can tell you he never recovered from the career-stifling blow of losing Don.

Hank's music is at Towson State near Baltimore. The current faculty could care less about their responsibilities to this man.