The Jazz.com Blog

September 02, 2009 · 0 comments

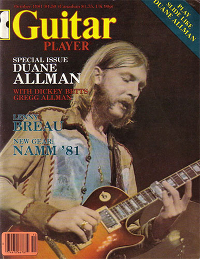

Duane Allman: A Rock Visionary on the Cusp of Jazz

Bill Barnes, a regular contributor to jazz.com, recalls some memorable musical performances from almost four decades ago, when a rock icon seemed on the verge of crossing over into jazz territory. Barnes shares his story below, and speculates on what might have happened, had Allman not died in a tragic motorcycle accident—at the age of 24. T.G.

It was an oppressively hot July day as my shaggy friends and I headed down toward Byron, Georgia, for the Second Annual Atlanta International Pop Festival. A year earlier its predecessor had actually been held in Atlanta—a month before a similar, but much more famous event in White Lake, New York. More than just a ‘pop’ or rock festival, the first AIPF had included an impressive, musically diverse lineup from Janis Joplin to Dave Brubeck, the latter being an encyclopedic nod to jazz.

However, the 1970 Byron festival had less musical diversity on its bill. With Jimi Hendrix as the star attraction and a lineup including the Chambers Brothers, 10 Years After, Grand Funk and Johnny Winter, promoter Alex Cooley probably felt little need. Other than the quirky Captain Beefheart group, there would be nothing resembling jazz on the program in Byron—or so we thought.

We struggled through the 100-mile traffic jam on I-75 and endured the merciless sun for hours before surly Hell’s Angels security guards let us through the gates onto the Byron Speedway. Finding our place among over 100,000 shamelessly wasted, semi-naked freaks, mostly squatting on blankets in various shades of psychedelic bliss, we had arrived just in time to hear the emcee gleefully tease, “That’s the Allman Brothers tuning up,” as the musicians adjusted their instruments and amplifier settings.

Their opening number was typical blues, but what followed was fresh, bold and genre-busting. When the band broke into “Every Hungry Woman,” I was intrigued. It was still recognizable as blues-rock, but with grittier funk intensity and the liberal usage of augmented 9th chords, clearly a deviation from the typical rock structure heavy with root-five voicings. However, it was “Dreams,” Greg Allman’s mystical, languid 6/8 piece, that convinced me something new was happening here beyond the limits of blues and rock- this was bordering on modal jazz. While “Dreams” wasn’t exactly on the same level as “A Love Supreme,” Duane Allman’s solo danced freely between the ionic and mixolydian, even as he switched to his trademark bottleneck midway. The drum kit duo of Butch Trucks and Jaimoe Johanson kept the whole composition airborne in an intricate waltz awash in a bluesy B-3 undercurrent, offsetting the impassioned growl of Greg Allman’s dusky suscadine-tinged vocals.

It was the introspective, tortured guitar work of Duane Allman that elevated this number beyond the boundaries of blues and rock. His phrasing was thoughtful, structurally simply, but harmonic complex—cliché-free and powerful. Later in the set, any doubts about Duane Allman’s jazzy aspirations were dispelled when the band tore into the explosive “Whipping Post.” From the forceful 11/8 intro to the dynamic dorian climax, the evidence was damning—these scruffy blues hounds from Daytona Beach were coming dangerously close to committing jazz.

The 1970 Byron performance of “Whipping Post” was more intense, streamlined and straight-ahead than the version captured live at the Fillmore East a year later, months before the young guitarist’s fatal motorcycle accident. At the Fillmore, the band expanded the arrangement, spacing out in an orbital ballet freeing the guitars for more involved modal exploration. It would be the greatest recorded performance of that signature tune, unfortunately a swan song for the guitar player who died just before his 25th birthday. For one so young, Duane Allman left some pretty deep footprints. But would he have played a significant role in shaping the fusion movement, or have ventured into the exploration of other jazz subphyla? When such a nova burns out quickly, there are often more questions than answers, but there are some clues.

As a much-in-demand session man at Muscle Shoals and Criteria studios, Duane Allman had plenty of exposure to other types of players. His guitar work appears on releases from R&B artists like Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin and Clarence Carter, and contributed to a variety of other sides alongside more mainstream rock personae from Boz Scagg to Derek and the Dominos. He had a genuine feel for funk and blues and was apparently starting to explore the jazz idiom as well.

According to Randy Poe, author of the Allman biography Skydog, his musical horizons were significantly expanded by bandmate Jaimoe Johanson’s record collection, especially his Coltrane, Miles and Tony Williams Lifetime albums. These influences leeched into his playing and, conversely, his playing helped expand the minds and open doors for young hardcore rock audiences in the South, much the same way Carlos Santana’s genre-crossing efforts had opened doors between Latino music, rock and, ultimately, fusion.

During his all-too-brief career as a studio musician Duane Allman actually contributed to only one jazz album, Herbie Mann’s Push Push, arguably the least ‘jazzy’ of Mann’s discography. But Allman’s presence on the session helped make this one of the most commercially successful of all the flautist’s recordings and offers a hint of what could have been.

Of course Duane Allman wasn’t the only prominent guitarist crossing the boundary into jazz during this period—along with the aforementioned Santana, who spent a considerable amount of time with John McLaughlin, there were others like former Yardbird guitarist Jeff Beck, whose Wired would include Mingus’s “Goodbye Porkpie Hat;” and the late Tommy Bolin, who recorded with Billy Cobham. However, I don’t believe Allman ever deliberately moved into the jazz realm—it’s more likely that he incorporated jazz into his particular style of playing, while never consciously making the distinction.

At least some of his modal ideas could have been absorbed by osmosis through playing with other session players during his countless record dates, many of which were uncredited. During his early studio days he shifted gears from soul to blues, to rock and roll as easily as some people change shirts. Along the way, he developed a jazz sensibility without abandoning the dynamic principals or phrasing of his blues, much like a trick rodeo rider astride two horses, with feet comfortably planted on each saddle. It worked for him because he always seemed to remain loyal to his own inner voice.

If he couldn’t feel it, he wouldn’t play it; in fact, he was known to call off a session if he wasn’t ‘in the zone.’ Because of this intensely personal commitment to musical fidelity, his solos always had a refreshingly organic, heart-to-wood quality. While many guitarists get lost in technique and theory, gimmickry and gadgetry, Allman shared a common trait with guitar favorites such as B.B. King and Jimi Hendrix as well as jazz icons like Benson and Burrell—he played right down to the wood.

After his death in 1971, the Allman Brothers Band’s recordings and concerts took a decided turn away from their more fusionesque material. Though Allman’s bandmate and guitar foil Dickey Betts was a gifted player and songwriter, his style leaned a bit more towards traditional country and as a result, the band’s sound would soon become firmly rooted in more Southern aesthetics. Under Betts’s lead, there would be few wild leaps and forays into the modal ionosphere. As for the other Southern bands that allegedly followed in the Allmans’ footsteps, their music remained largely uncontaminated by jazz, Marshall Tucker Band’s prosaic flute notwithstanding. Had Duane lived, it’s likely that his band’s evolution toward jazz would have continued, but we’ll never know. All we do know is that, in his absence, it became less progressive.

I was fortunate to hear this band with its original members intact on one more occasion. December 5th, 1970 is a date I’ll never forget- it was the one time I would see Duane Allman play up close, in a club setting. The band’s star was rising—they were now a concert act with two albums to their credit, filling stadiums to capacity wherever they performed. A landmark live recording at Bill Graham’s fabled Fillmore East was yet to come. But the Allmans had already been booked into a Greenville, North Carolina nightclub called the Music Factory, a huge concrete rectangle of a beer hall that catered to the East Carolina University crowd, and there was no getting out of the date.

I was a student at a college within just an hour’s drive and jumped at the chance to hear them again. That Saturday afternoon, some friends and I piled into a Dodge van and headed toward Greenville, partying all the way down, arriving a few minutes before the opening set.

It must be said that, when it came to embracing late sixties counterculture sensibilities, many in the Carolinas had lagged behind the rest of the country. Not surprisingly, the crowd that night was an odd mix of long-hairs in bell bottoms and jean jackets and the more typical rowdy, shag-dancing frat boys with their trim Caesar haircuts, alpaca sweaters and Ban-Lon shirts. Back then, we “effete snobs” with our fledgling pony tails would often refer to these gentrified crackers as “grits,” too stylish and affluent to be classified as rednecks, but definitely un-cool, out of touch—not the Allmans’ ideal audience.

The band eventually meandered onstage amidst a Pabst and Bud-fed barrage of hooting from the grits, all with the same homily: “’Whippin’ Post!’ Play ‘Whippin’ Post!’ Come on, we want to hear ‘Whippin’ Post!’” Ad nauseam. Duane Allman, barely 24 years old but seeming much older, was in no mood. With a look on his face like he had just swallowed a palmetto bug, he moseyed up to the microphone, pulled his Les Paul to one side and snarled: “We’re not a God-damned jukebox—I call the tunes!” With that, the band ripped into one of their slide blues numbers, “Trouble No More.”

The crowd settled down, but the first set was rough, the band seemed unsettled, sound system balance all askew. Fortunately, after a brief intermission in which technical issues seemed to have been resolved, the boys took no prisoners in the second set, ending with a rousing performance of Dickey Betts’ haunting instrumental, “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.” Duane played with an angry intensity, cutting like cold steel, his phrasing slightly tinged with sadness. The band was molten-hot, vulcanized by the flawless, synchronized precision of Trucks and Johanson. It’s hard to imagine them ever sounding better. They left the stage to thunderous applause, cheers and foot-stomping, which showed no signs of abating.

If the motorcycle crash had not taken his life in 1971, Duane Allman would have been in his early sixties today. Imagine what paths his playing would have taken in the interactive Internet age, after decades of cross-pollenization occurring between jazz, blues, r&b, hip-hop and rock ‘n roll. Even more tantalizing is the thought of how he would have influenced new generations of guitar players. As it stands, in his brief life he had opened the door a bit wider for many aspiring guitarists sitting on the borders between jazz and more comfortable, less intimidating styles. Would he have completely abandoned his bottleneck, blues riffs and band of Brothers to take up permanent residence on the ‘dark side’ of fusion or avant-garde? Probably not. But I hate the idea of this unique guitarist being remembered only as an R&B session player, Eric Clapton sideman and a founder of southern rock. He was so much more, a formidable supernova who could have easily toed the technical mark with the likes of Scofield, Kahn and Metheny.

After the last set at the Music Factory in Greenville on that late Autumn night in 1970, the audience kept stomping and clapping, until the Allmans drifted back onstage for their encore. Duane Allman once again approached the mic, this time with the hint of a smile at the corners of his mouth: “Well, you’ve never heard this one before.” Berry Oakley started the unmistakable rumbling 11/8 ostinato, launching the band into “Whipping Post.” I will never forget the raw, unbridled force of Duane’s solo—as always, that night he played it right down to the wood.

This blog entry was posted by Bill Barnes

Tags:

Comments are closed.