The Jazz.com Blog

September 27, 2009 · 1 comment

A Forgotten 1959 Masterpiece

The folks at Sony have worked overtime on promoting anniversary reissues this year. But the 50th birthday of one classic 1959 album in their catalog has gone by unheralded by the company and the media—even though this LP may have been the most influential of them all.

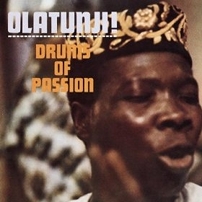

Next week will mark the 50th anniversary of the final recording session for Drums of Passion, the path-breaking release by Babatunde Olatunji that helped usher in the age of world music, and exerted a crossover influence in the realms of jazz and rock that can still be felt today. By any measure, Drums of Passion stands out as one of the least likely—and most inspiring—success stories from the 20th century music business

The late Tom Terrell argued that Drums of Passion was "note for note, rhythm for rhythm, groove for groove, vibe for vibe, and influence for influence—the single most important recording of the last century." This assessment was based on more than the five million copies sold in the US alone, or the release's validation of traditional African music as a commercial property. The real evidence emerges when we look at what happened elsewhere in the music world during the decade following the release of Olatunji's pioneering album.

In jazz, a host of artists from John Coltrane to Max Roach, embraced a more overt pan-African sensibility during the 1960s, and the rhythmic textures of their music revealed marked similarities with Olatunji's aesthetic vision. Even African styles of apparel and nicknames started showing up on the jazz bandstand and in the audience. But the biggest transformation took place in the rhythm section. The drum solo now happened more often, lasted longer, and erupted with greater vehemence. Even when accompanying, percussion stood out as louder and more demonstrative than in previous decades.

This was true not just in jazz, but even more in popular music, which developed a love affair with the drum that continues until this day. There were virtually no drummers who were pop stars in 1950s rock, but ten years later that had all changed, and the beat, primal and hypnotic, almost rivaled the electric guitar as the defining sound of the age. If one is looking for the turning point, the precedent that anticipated these changes, no better harbinger will be found than Drums of Passion.

Yet if Drums of Passion changed how music was played, it also shaped how audiences listened. In the 1950s, what we now call "world music" was the plaything of Les Baxter, Martin Denny and other expropriaters of aural exotica, whose recordings were to real ethnic music what Christy's Minstrels were to Robert Johnson and Son House. Drums of Passion signaled the end of this Hollywood-ized version of the Third World, and revealed that the musicians of Africa and other less economically developed parts of the globe were more than capable of presenting their own musical traditions to audiences—and of enjoying a hit record in the process.

The story behind Drums of Passion is as uncharacteristic and surprising as the music itself. Michael Babatunde Olatunji was born in 1927 in Ajido, a fishing village in southwestern Nigeria. One day in the late 1940s, the youngster read about the Rotary Foundation's scholarship program in a copy of Reader's Digest. He applied for and won the fellowship, which gave him the chance to study at Morehouse College in Atlanta—where Dr. Martin Luther King had been a student only two years before Olatunji's arrival on campus. After graduating, the drummer moved to New York, where he studied public administration at NYU. To help fund his education, he started a percussion ensemble.

By all accounts, Olatunji's performances were exciting spectacles, but they might not have been preserved on record without the intervention of John Hammond, a daring talent scout whose "finds" over the years, included Bob Dylan, Billie Holiday, Aretha Franklin, Bruce Springsteen, and Count Basie. Hammond had such a sure touch and glamorous associations, that his biographer Dunstan Prial doesn't even mention Drums of Passion in passing in his 350-page book The Producer. Yet this was one of Hammond's finest moments. He heard Olatunji at Radio City Music Hall, where the Nigerian was wowing the audience with his ensemble's combination of drumming, dancing and chanting. The visceral excitement of the band was palpable, yet John Hammond was probably the only decision-maker at Columbia who would have seen this as the starting point of a commercial record.

I have written elsewhere of the impact of long stretches of drumming on an audience. Since Andrew Neher's clinical work (published around the same time as Olatunji's recording), we have known that exposure to these rhythms can change our brain waves in a process known as entrainment. But it is only in recent years that evidence has emerged that a ten minute immersion in drumming not only alters our levels of adrenalin, noradrenalin and cortisol, but can even improve the immunological robustness of our bodies. If you want to understand what this means in the most basic layman's terms, just go to a concert where drums predominate and look at the effect on the people around you in the audience. Olatunji may not have had these clinical factors in mind when he recorded Drums of Passion, but his listeners were still very much put under his spell by the entrainment and not just the entertainment value of his music.

The album was a runaway success. And for most of these record-buyers, Drums of Passion was their first opportunity to hear African music without it being diluted and packaged by some intermediary. Their enthusiasm was a rare example of the mass market choosing the real thing over a shoddy imitation. Then again, maybe the general public would choose the real thing more often, if the media and music industry gave them the opportunity. Yes, fifty years may have elapsed, but not only can we still enjoy Drums of Passion—we also might still learn from it.

This blog entry posted by Ted Gioia

Tags:

I was just thinking about Drums of Passion earlier today. You are absolutely correct as to its huge influence. Back in the early 60's in NYC, it was in constant rotation on Symphony Sid's show, along with Coltrane, Miles, etc. Even Murray the K, later known, at least t hmself, as the Fifth Beatle,would use Akiwowo as background on his WINS rock and roll show.